Over the weekend, Politico announced that the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) and Food Marketing Institute (FMI) were finally going to launch their long-threatened $50 million campaign to promote voluntary “Facts Up Front” labels on food packages.

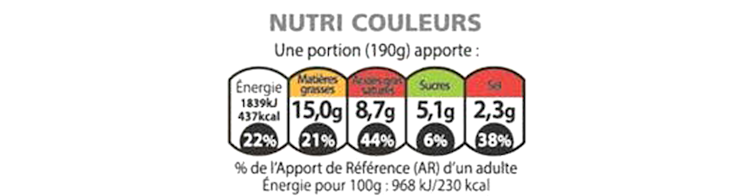

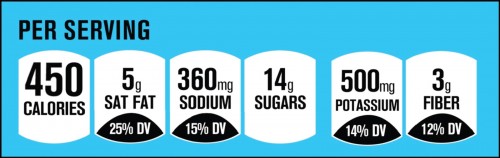

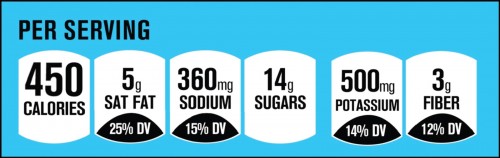

In case you never noticed these labels—and I doubt most people do—here is an example:

GMA and FGI conducted their own survey. This—no surprise—found that people love Facts Up Front labels, but I find that hard to believe. Neither do others, according to Politico reporters.

For what $50 million will buy, see yesterday’s Washington Post, page A5 (thanks Politico).

Recall the history

Facts Up Front (formerly known as Nutrition Keys), was originally launched as an end run around what the FDA was then trying to do with front-of-package labeling initiatives. This happened early in 2011.

The GMA/FMI ploy brought the FDA’s initiatives to a halt—despite the agency’s investment in two Institute of Medicine (IOM) studies to establish a research basis for front-of-package labels.

These, in turn, followed on the heels of the food industry’s ill-fated Smart Choices—an attempt to promote highly processed foods as healthy.

GMA/FMI’s goal was to head off any possibility that the FDA would mandate red, yellow, and green traffic light signals.

Red signals might discourage consumers from buying products made by the companies GMA and FMI represent.

The food industry had cause to worry. The IOM was considering—and eventually published—a front-of-package scheme similar to traffic lights. It used checks or stars to evaluate the content of calories, saturated and trans fat, sodium, and sugars, all nutrients to watch out for.

GMA/FMI got its much more complicated—and, therefore, harder to understand—Nutrition Keys out first. This preempted the IOM recommendations.

The FDA gave up. The two IOM reports went into a drawer and the FDA has done nothing with them.

Why is GMA/FMI doing this now?

Surely, it is no coincidence that GMA/FMI is rolling out this campaign on the heels of Let’s Move!’s triumphant release of the FDA’s new food labeling proposals.

They must be worried that the FDA will unearth the two IOM reports, adopt the IOM recommendations, and start rulemaking for front-of-package labeling.

One sign of the food industry’s strategy comes from Bruce Silverglade, who for years was head counsel for the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), but has now revolved to a Washington, DC law firm that represents food companies. He told Politico:

The general view in the industry is that nutrition information has really moved to the front of the pack. What FDA is doing is essentially proposing a new model of an old dinosaur.

As Michele Simon tweeted: “that comment…is rich coming from ex-@cspi lawyer who fought for label.”

What’s wrong with Facts Up Front?

Plenty.

The IOM recommended that front-of-package labels be:

- Simple: easy to understand

- Interpretive: putting judgments in context

- Scaled: indicating good, better, and best

Facts Up Front does none of the above.

Facts Up Front is a tool for selling, not buying.

Its purpose is to make highly processed foods look healthier, whether or not they really are.

Whether slightly better-for-you processed foods will help anyone make better food choices and be healthier remain open questions.

What should happen now?

With Let’s Move! really moving, this seems like a great time to urge the FDA to pull out those IOM reports and get busy on a front-of-package labeling method that will really help the public make healthier dietary choices.