HuffPo mystery solved and no harm done

The mysterious ghostwriting episode I discussed earlier today (see below) is now explained. Apologies to the Huffington Post.

I received a flurry of messages in response to the post, including an apology from Linda Gibbs, Deputy NYC Mayor for Health and Human Services. She reminds me that we spoke months ago (early May, as it turns out) about my willingness to edit and sign an op-ed about the proposed SNAP ban prepared by her staff that was to be submitted to the New York Times.

I vaguely remember reviewing such a piece and approving its submission. When I heard that the Times had rejected the piece, I promptly forgot about it.

As far as I can tell from reviewing my sent and deleted messages from Linda Gibbs, none mentioned co-authorship with Geoffrey Canada, and the piece submitted to and published in the Huffington Post does not mention the involvement of the NYC health department.

The press director for Harlem Children’s Zone tells me that the piece was later submitted to two other publications that also turned it down. I was not cc’d on either of those submissions or on the one to the Huffington Post.

Hence my confusion.

For the record, I am happy to have the piece published with my name on it, to be working with the NYC health department and Linda Gibbs, and to be a co-author with Geoffrey Canada, who I very much look forward to meeting one of these days.

And here’s what all the fuss was about:

Does HuffPo use ghostwriters? “My” piece with Geoffrey Canada!

A colleague congratulated me yesterday on my Huffington Post article—co-authored with Harlem Children’s Zone’s Geoffrey Canada—on SNAP (food stamp) benefits and sodas.

I was amazed to see it. I don’t recall writing it and I don’t believe I have ever met Mr. Canada, although I would be delighted to do so. The article does indeed reflect my views but does not read like something I wrote.

So I guess thanks are due to Mr. Canada or to the ghostwriter. If anyone knows the story behind this, please tell!

Here’s the article:

NYC’s SNAP Sugary Beverage Ban Is the Right Idea

Marion Nestle and Geoffrey Canada

Posted at HuffingtonPost.com: 7/15/11 05:26 PM ET

New York City’s proposal for a two-year pilot to ban the use of food stamps to buy sugar-sweetened beverages is the right idea at the right time. It is a sound approach aimed at minimizing consumption of soda and other beverages stocked with added sugars at a time when we desperately need new interventions to combat the surge of obesity and diet-related disease across the country. A ban would also act as a counterweight to the soda industry’s efforts to solidify its products as part of the typical everyday diet. From our diverse perspectives — informed by a lifetime writing and teaching about food systems and policy, and decades spent helping kids in poverty beat the odds — we join together in a firm belief that this effort must be approved.

Increasingly strong evidence points to sugary drinks as major contributors to obesity and diabetes. The least-fortunate Americans suffer the most, evidenced by health disparities between rich and poor, white and non-white. For example, obesity and Type 2 diabetes are twice as prevalent in New York City’s poorest households as in the wealthiest. And these disparities persist nationwide. Overall, 44 percent of African Americans and 38 percent of Hispanics in the United States are obese, versus 32 percent of whites. Obesity itself increases the risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, cancer, high cholesterol and heart disease, all conditions that disproportionately affect the poor.

New York’s proposal for a two-year pilot project to remove sugar-sweetened beverages from allowable SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or food stamp) benefits is based not only on evidence linking these beverages to obesity, but also the fact that sugared drinks have absolutely no nutritional value. Considering that the SNAP program is, both in title and purpose, a nutrition assistance program aimed at combating food insecurity, this in itself is a compelling basis for excluding sugared drinks from the allowable purchases with SNAP dollars. The proposed ban, which would have to be approved by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), is in line with the SNAP program’s approach to other non-essential items: the federal government already prohibits use of SNAP benefits for alcoholic beverages, for example. And the WIC (Women, Infants and Children) program, which the USDA also runs, restricts benefits for low-income mothers to only a limited number of nutrient-rich foods.

Some have criticized New York City’s proposal as patronizing to SNAP recipients, but the ban would not stop SNAP recipients from buying sodas. They just wouldn’t be able to use SNAP benefits for them. And, more critically, we must begin to think creatively about mechanisms to change our food environment for the better. The rates of soda consumption in our poorest communities cannot be explained by individual consumer preferences alone, but rather are linked to broader issues of access and affordability of healthy foods in low-income neighborhoods, and to the marketing efforts of soda companies themselves. Four in 10 residents of high-poverty pockets of Harlem, Brooklyn and the South Bronx drink four or more sugary drinks daily, compared with one in 10 Upper West Side residents.*

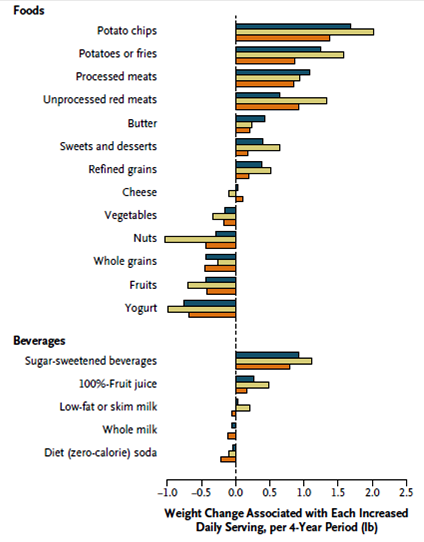

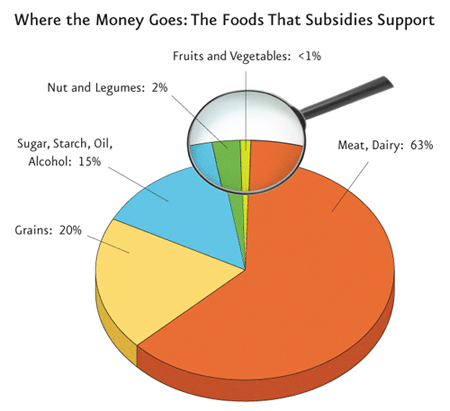

Certainly, as the 2012 Farm Bill looms, a larger conversation about using federal policy to promote healthful eating is warranted. We should focus on ways to make healthful foods more available to low-income families — for instance, by doubling the value of SNAP benefits when used for fruits and vegetables, or promoting incentives to establish grocery stores and community gardens in inner-city areas. There is no reason that these ideas cannot work in tandem with a policy that eliminates the federal subsidy for soda.

Soda companies hate New York City’s proposal, of course. In 2010 Coca-Cola, Pepsi and the American Beverage Association lobbed $22 million at federal officials, according to the House of Representatives’ Office of the Clerk. This lobbying has killed soda tax initiatives and gotten the industry’s sugar-soaked products into schools (though not here in New York City schools, where they cannot be served). Soda companies reach millions more kids through targeted Internet and social media campaigns. As soda sales in the U.S. have declined, they are increasingly marketing their products to children and youth in low-income areas, and they have successfully co-opted health professional groups with partnerships, alliances and grants. As a result of these efforts, they have created an environment in which it is considered normal in many households to drink sugary drinks all day.

In 2010, SNAP benefits went to more than 40 million people at a total cost of more than $68 billion. According to USDA figures for 2009, approximately six percent of this funding — more than four billion dollars a year — is spent on sugar-sweetened beverages. Given this scale, and the potential health impacts of soda consumption, is time for policy makers to rethink the place of these beverages in a federally funded nutrition assistance program. We hope the USDA will approve New York City’s project.

*Alberti P and Noyes P. Sugary Drinks: How Much Do We Consume? New York, NY. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2011.

Follow Marion Nestle on Twitter: www.twitter.com/marionnestle

Update: 11:00 a.m.

Dear Dr. Nestle,

Apologies for your mistaken attribution in the Geoffrey Canada piece published on Friday. We received an email from the communications director of the Harlem Children’s Zone indicating you were to be bylined on this article. The link to the post now goes to a post bylined just by Mr. Canada.

Sincerely,

Claire Fallon, Associate Blog Editor

The Huffington Post