Trans-Pacific Partnership’s food issues: rice, sugar, Malaysian palm-oil, trans fats

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations are taking place this week in Maui, as usual, in deep secret.

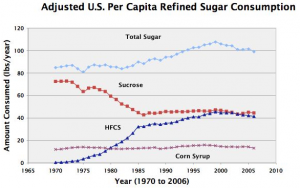

Doug Palmer of Pro Politico describes the major food issues: dairy, origin names, pork, rice, and sugar. The issues come down to market share. Every country wants to protect its own products but have free access to markets in other countries.

Although not a food, tobacco best explains why the TPP makes people nervous. US tobacco companies want the TPP to open new markets. But one of the TPP provisions is said to allow corporations sue governments that pass rules that might hurt the corporation’s business. Philip Morris sued Australia over its “plain packaging” law and is now suing Great Britain.

The US position is supposedly that a country’s measures to protect the health of humans, animals, or plants should not be in violation of the TPP, and that challenges to tobacco-control measures should be cleared with TPP partners. Malaysia, for example, has proposed to exempt tobacco-control measures from challenges under TPP.

Malaysia?

The State Department has just taken Malaysia off its list of the worst countries for human trafficking (see the July 2015 Trafficking in Persons Report).

What a coincidence. This allows Malaysia to participate in TPP negotiations.

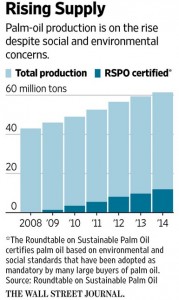

But what bad timing. The Wall Street Journal has just published a harrowing story about the de facto slavery of palm-oil workers on Malaysian plantations (the New York Times just did one on “sea slaves” forced to fish for pet food or animal feed).

As Rainforest Action Network said of the Malaysia story in a press release:

July 27, 2015 (SAN FRANCISCO) – The Obama administration has removed Malaysia from the list of worst offenders for human trafficking and forced labor today, one day after The Wall Street Journal published an extensive report on human trafficking and forced labor on Malaysian palm oil plantations that directly supply major U.S. companies. Malaysia is one of 12 nations in the contentious Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, and inclusion of a country with the lowest ranking in the State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report would be problematic for the administration.

And then, there’s the trans-fat connection: The US demand for replacement of partially hydrogenated vegetable oils has pushed Malaysia and other palm-oil countries to produce more palm oil, faster.

The Wall Street Journal explains:

Palm oil has been repeatedly named on the U.S. Department of Labor’s list of industries that involve forced and child labor, most recently in 2014. Activists have blamed palm-oil plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia for large-scale deforestation and human-rights abuses. Oil palm growers respond that the palm tree, a high-yield crop, is a useful tool for socioeconomic development.

The TPP is hard to understand, not least because negotiations are secret. In giving the President the go-ahead to sign the agreement, Congress made two stipulations:

- Congress must be notified 90 days in advance of signing.

- The terms of the agreement must be disclosed to the public 60 days prior to signing.

At least that. TPP deserves very close scrutiny.