Soda tax controversy goes international

My monthly first Sunday Food Matters column in the San Francisco Chronicle:

Q: I hear that the Mexican government wants to increase taxes on sodas as a way to fight diabetes. The soda industry persuaded voters to defeat soda taxes in Richmond and El Monte last year. Won’t it do the same in Mexico?

A: It might. I’m just back from a lecture trip to Mexico City where I heard plenty about the proposed soda tax and the industry’s response to it.

Last month, the Mexican government proposed an additional soda tax of one peso (about 8 cents) per liter. The idea is to raise $1.5 million per year while discouraging soda consumption, thereby helping to reduce the country’s high prevalence of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

Mexicans drink lots of soda. By some estimates, average per capita consumption is 50 gallons a year, the highest in the world. It’s no coincidence that more than 70 percent of Mexicans are overweight or obese, and around 15 percent have Type 2 diabetes, a prevalence that terrifies health officials. This type of diabetes, if undiagnosed and untreated, can lead to blindness or foot amputations.

‘Nutrition transition’

Mexico is a classic example of a country in “nutrition transition.” As the economy improves, people increasingly buy high-calorie ready-made foods, put on weight, and raise their risk for diabetes. Meanwhile, the poorer segments of the population continue to experience high levels of stunting, iron-deficiency anemia and vitamin A deficiency.

This makes obesity a relatively new problem in Mexico, one widely understood to result from the introduction of processed foods – especially sodas – into the Mexican food market.

I could easily see how deeply sodas are embedded in Mexico’s food culture. Sodas were advertised and available everywhere. And they come in enormous three-liter bottles that cost less than the price of bottled water – only 17 pesos ($1.35) each. Clean water is not always available, making sodas the easy choice.

Sodas are cheap because Mexico grows its own sugarcane and sells it at market prices. We, however, artificially support the higher price of U.S. sugar through tariffs and quotas. That’s why our sodas are made with high fructose corn syrup. We subsidize corn production so corn syprup costs less than sugar.

Some people think cane sugar tastes better than high fructose corn syrup, although controlled taste tests don’t always back this up. It’s ironic that U.S. supermarkets now carry, at highly inflated prices, Mexican Coca-Cola sweetened with cane sugar.

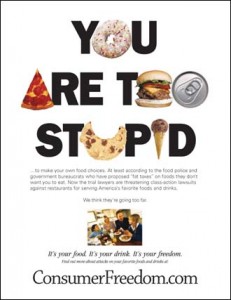

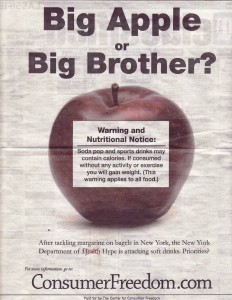

Industry efforts to defeat the Mexican soda tax have been ferocious, just as they were in Richmond and El Monte last year. Producers argue that if the tax really does decrease consumption, it will cause hundreds of thousands of jobs to be lost.

I saw a newspaper advertisement from the Mexican Beverage Association that not only attacked the science relating soft drinks to obesity, but extolled the health benefits of sodas: “Sugar is nutritious; it’s a carbohydrate. Carbohydrates are essential for life. Sugar is indispensable for the brain. Soft drinks hydrate and bring energy.”

An ad from the sugarcane industry also threatened job losses – “The tax will generate unemployment and discourage productivity and investment” – and noted that workers and the poor will bear most of its burden.

The big questions

As with any such initiative, the big questions are whether the tax is likely to reduce soda consumption, obesity and diabetes, and whether the revenue will be used for widely beneficial public health purposes. Mexico’s Congress will have to address these questions when it votes on the tax in the weeks ahead.

In the meantime, a coalition of consumer and health groups, in part funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, has been putting posters in subway stations that illustrate the amounts of sugar in soft drinks. The groups are actively advocating for the soda tax and for using its funds to provide free potable water in schools – something that does not now exist. But TV stations have refused to carry their ads for fear of losing soda advertisers.

Like their U.S. colleagues, Mexican public health authorities are searching for effective ways to reverse obesity trends. Sugary drinks are an easy target. Taxing them might happen despite industry opposition – especially if the funds are earmarked for clean water.

Editor’s notes: Marion Nestle will discuss her new book, “Eat, Drink, Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Food Politics,” with Narsai David at the Commonwealth Club on Oct. 15 at 6 p.m., and at Book Passage in Corte Madera on Oct. 19 at 11 a.m.

She is also receiving the James Beard Foundation Leadership Award for her writing about how science and public policy influence what we eat. The award ceremonies are Oct. 21 at the Hearst Tower in New York.

Marion Nestle is the author of “Eat, Drink, Vote,” “Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics,” “Food Politics” and “What to Eat,” among other books. She is a professor in the nutrition, food studies and public health department at New York University, and blogs at www.foodpolitics.com. E-mail: food@sfchronicle.com