“Natural” on food labels? Ain’t necessarily so…

It’s the first Sunday of the month and time for my monthly Food Matters column in the San Francisco Chronicle. In this one, I deal with the annoying “natural” on food labels, a term that the FDA prefers not to define.

Q: I am doing legislative research on food policy for one of my state’s senators on the definition of “natural.” As things stand, it’s difficult for consumers to understand what “natural” means on food labels. How should the FDA define this term so it is accurate and not misleading?

A: I was traveling in New England when your question arrived, and it sent me right to the nearest Hannaford supermarket. Hannaford makes this research easy. Sections everywhere in the store are labeled “organic and natural.”

Organic is no problem. Certified organic products must be made with ingredients raised or grown without artificial fertilizers, pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, irradiation, sewage sludge or genetic modification.

But what are we to make of Honey BBQ All Natural Potato Chips containing 20 ingredients, among them monosodium glutamate, yellow food color, and undoubtedly genetically modified corn and soy, but “no hydrogenated fats and gluten free”? Or Healthy Natural Dog Food containing meat by-products and other such things but “no artificial preservatives, colors or fillers”?

The Food and Drug Administration is not much help. Its answer: “From a food science perspective, it is difficult to define a food product that is ‘natural’ because the food has probably been processed and is no longer the product of the earth. That said, FDA … has not objected to the use of the term if the food does not contain added color, artificial flavors or synthetic substances.”

If you have made it through all the not’s in this non-definition, you can begin to understand how the FDA can allow high-fructose corn syrup to be “natural.” Even though enzymes, synthetic or not, are required to convert cornstarch to this mixture of glucose and fructose, it does not contain artificial colors or flavors.

But the products I mentioned do. Yellow No. 5 is an artificial color. You must assume that the corn or soy in any “natural” product is genetically modified unless the label says GMO-free or Certified Organic. You may be someone who has a hard time considering GMO ingredients “natural.”

In the last decade, new products marketed with “natural” claims have proliferated, and it’s easy to understand why. Marketers love the term. “Natural” sells products, not the least because consumers consider it a synonym for healthful and, often, for organic. Anyone would rather buy “100 percent natural seltzer water” – “calorie-free, no sugar, no sodium, gluten-free” (things never found in water) – than plain seltzer.

While “natural” does not necessarily mean “healthy” or even “healthier,” it works splendidly as a marketing term and explains why many junk-food manufacturers are switching from expensive organic ingredients to those they can market as “natural.”

The FDA isn’t fixing this situation because, according to a statement in response to a petition by Center for Science in the Public Interest, it’s “not an enforcement priority.”

Manufacturers of highly processed foods could not be happier with this nondecision.

In the absence of regulation, enter litigation. In recent years, advocacy groups have filed dozens of lawsuits seeking to ban “natural” claims on foods containing ingredients that seem unnatural, especially those genetically modified. Judges tend to say it’s the FDA’s problem and are calling on the agency to define the term.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which is responsible for meat and dairy products, has attempted to clarify what it means by “natural.” Its Food Safety and Inspection Service says meat and poultry can be labeled “natural” when they are minimally processed and have no artificial flavorings, colorings or preservatives. USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service says “naturally raised” means the meat must come from animals produced with no hormone growth promoters, no antibiotics and no animal by-products.

How about all of the above? And if the public really can’t tell the difference between “natural” and “organic,” the closer the definition of “natural” is to that of “organic,” the less confused they will be.

Perhaps you could advise the senator to begin with the organic standards. And then toss in working definitions that exclude anything synthetic, artificial and more than minimally processed.

You should expect food industry lobbying against this idea to be fierce. But the public will be better served if the compromises in defining “natural” come at the end of the negotiations rather than at the beginning.

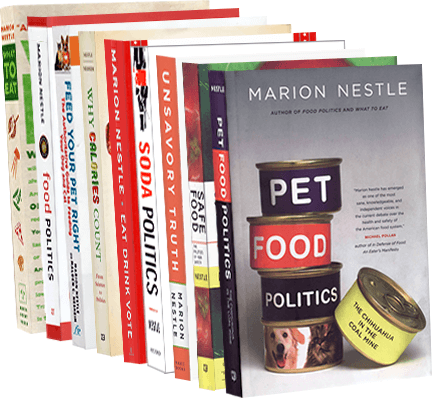

Marion Nestle is the author of “Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics,” “Food Politics” and “What to Eat,” among other books. She is a professor in the nutrition, food studies and public health department at New York University, and blogs at www.foodpolitics.com. E-mail:food@sfchronicle.com