Weekend reading: The demise of the Ogallala Aquifer

Lucas Bessire. Running Out: In Search of Water on the High Plains. Princeton University Press, 2021.

The website blurb for this book says it is “An intimate reckoning with aquifer depletion in America’s heartland.”

Yes, but it’s more than that. It’s a deeply personal account of the author’s attempt to make sense of and come to terms with his family’s history on land on the plains of Western Kansas. This land was once occupied—and not all that long ago—by Native American tribes since murdered or driven out by white settlers. This same land was once watered by rivers from an ancient underground source, but now so depleted by irrigation that it—like the Indians—is threatened by extinction.

The author, an anthropologist at the University of Oklahoma, grapples with his family’s role in this depletion and his own complicity while coming to terms with his relationship with his long estranged father. I read this book as a history of the great plains viewed through a personal and familial memoir that reads like a novel.

If you are even remotely interested in why farmers on the great plains are not doing more to preserve this essential water source, start here. It’s revelatory.

…corporate profits are a key part of the aquifer depletion puzzle. It should have come as no surprise. The scale of industrial farming is staggering. Southwest Kansas is home to some of the nation’s largest corporate feeders, beef- and poultry-packing plants, slaughterhouses, dairies, milk-drying plants and hog farms. More than 2.5 million beef cattle live there in feedlots that handle tens of thousands of animals. Just across the Oklahoma line, one company processes 5.6 million hogs per year in its plant…Multinational meat-packing companies operhoe slaughterhouses that process several thousand cattle each day. All are billion-dollar businesses. They drive farmers’ choices to produce corn, silage, sorghum, or alfalfa. Their profits depend on aquifer depletion. In other words, there is a multbillion-dollar corporate interest to prevent regulation and to pump the water until its gone [p. 78].

He documents goverment collusion with absentee corporate landowners who could care less about what happens to real farming communities. Near his family’s home, “at least 60 percent of the farmland is owned by nonresidents’ [p. 80].

In the 1940s, the supply of water seemed endless and the opportunity to preserve the aquifer was lost. “Faith in the abundance of these waters put an end to the more sustainable farming techniques tht were beginning to be adopted by the end of the 1930s, as well as the progressive policies that accompanied them. One historic opening was lost with them” [p. 89]

Nobody talked about what settlers did to the Indians.

We confined the horrors of eradication [of the Indians] to a cartoonish lost world; one that we thought was entirely disconnected from our own. We did not relate past events to the banal activities of irrigation farming or the way we grew up or the pumping of the subterranean aquifers. Like the extermination of buffalo and the toxid fogs and the torturous confinement of defiant voices, these events were not openly discussed and their remnants were never tied to the present. Cordoning them off from conversation meant that their significance was largely blocked from our memories, too [p. 130].

He struggles with these questions:

So where can a true reckoning with depletion begin and where does it end? With a strategy to update management practices through more precise forms of modeling and expertise? With the innovation of more-efficient irrigation technology and crop varieties that require more water? With a sociology that details how agrarian capitalism drains water and wealth from the Plains to enrich investors elsewhere? With a diagnosis of how this case illustrates White supremacy, toxic masculinity, or the sentiments and logics of settler colonialism? With a chart of the ways aquifer losss combines with climate chage to make ours an era of planetary ends? With an optimism that things aren’t really as bad as they seem? [p. 168].

Why care about the Ogallala Aquifer? “…depletion comes back into focus as one of the wider movements that erode democracy, divide us from one another, and threaten to make exiles of us all” [p. 173].

Bessire points out that everyone knows what could be done, and right now, to reverse the depletion and conserve what remains. “Examples of success can be found across the Ogallala region, whree farmers from Nebraska to Texas are organizing and leading related efforts to slow decline” [p. 174].

His book is a call for citizen action. It would be good to take him up on it.

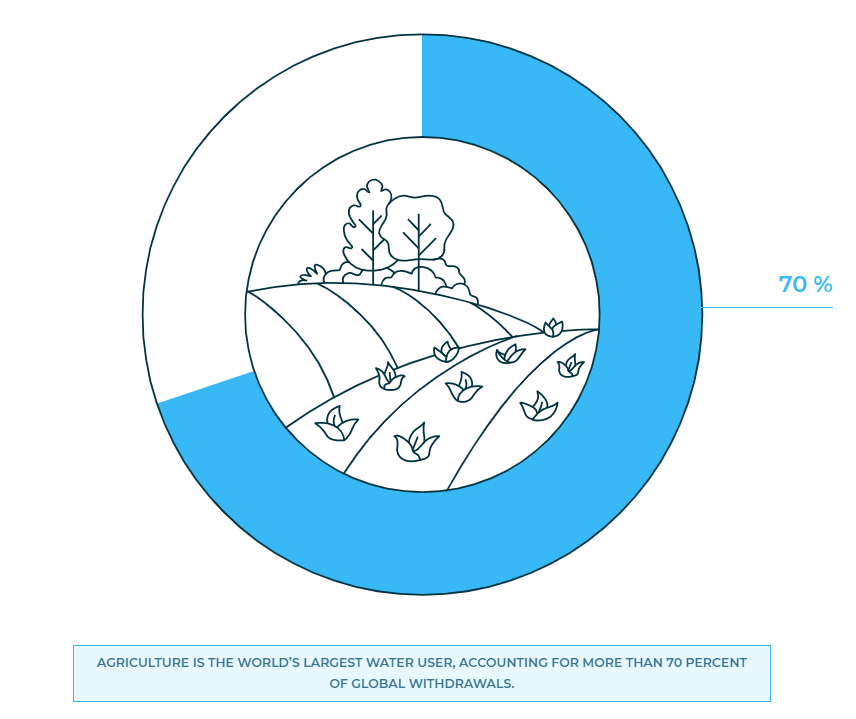

Everyone needs to pay attention to water use, and the teaser and the report state the policy recommendations.

Everyone needs to pay attention to water use, and the teaser and the report state the policy recommendations.