Weekend reading: Thinking about food systems advocacy

The United Nations has issued a digital Food Systems Thinking Guide for UN Resident Coordinators and UN Country Teams with tools and information for working collectively towards food system transformation.

It is intended as a working draft. It provides an easy mechanism for immediate feedback.

You have to do a lot of scrolling. When you do, you will get to key questions:

- What is a food systems approach and why does it matter?

- What is the state of food systems in my country?

- Who are the actors influencing the foods system?

- What are barriers and entry points to food system transformation?

- How can I integrate foods systems approach into programming?

- How can I communicate and advocate for foods systems transformation?

I took a look at the actors. This section provides resources for engaging with stakeholders.

I also looked at barriers. It lists things to consider and provides resources.

And I looked at communication strategies. This one is much more complete and has useful videos and key messages along with the resources.

I see this as an advocacy toolkit focused on food system transformation. Happy to have it. Try it and give the UN some feedback on it to make it even better and more complete.

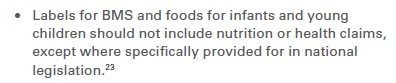

I’m not sure how to interpret the “except” phrase, except that our FDA must think that the health claims on a product like this are entirely acceptable, whereas they would not be allowed in many other countries. [Reference 23 refers to UN General Assembly Resolution 63.23.]

I’m not sure how to interpret the “except” phrase, except that our FDA must think that the health claims on a product like this are entirely acceptable, whereas they would not be allowed in many other countries. [Reference 23 refers to UN General Assembly Resolution 63.23.]