Today, the Lancet publishes three major papers on ultra-processed foods and human health: science, policy, and politics (I am a co-author on the policy and politics papers). Here’s Peter Bond’s photo, the logo for the series.

THE PAPERS

I. SCIENCE

Ultra-processed foods and human health: the main thesis and the evidence. Carlos A Monteiro, Maria LC Louzada, Euridice Steele-Martinez, Geoffrey Cannon, Giovanna C Andrade, Phillip Baker, Maira Bes-Rastrollo, Marialaura Bonaccio, Ashley N Gearhardt, Neha Khandpur, Marit Kolby, Renata B Levy, Priscila P Machado, Jean-Claude Moubarac, Leandro F M Rezende, Juan A Rivera, Gyorgy Scrinis, Bernard Srour, Boyd Swinburn, Mathilde Touvier.

This first paper defines ultra-processed foods and diets as including three specific elements:

- Industrially produced

- Made from cheap ingredients extracted from whole foods, combined with additives

- Designed to maximize industry profits

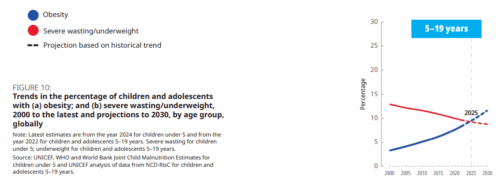

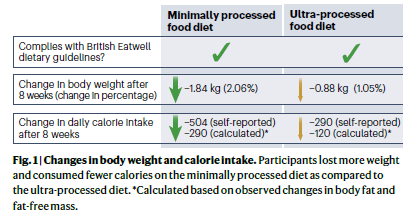

It presents the evidence in support of three hypotheses about ultra-processed dietary patterns. These:

- Globally displace traditional diets based on whole foods.

- Reduce dietary quality.

- Are a key driver of the escalating global burden of diet-related chronic diseases.

II. POLICY

Policies to halt and reverse the rise in ultra-processed food production, marketing, and consumption. [Full text here] Gyorgy Scrinis, Barry M Popkin, Camila Corvalan, Ana Clara Duran, Marion Nestle, Mark Lawrence, Phillip Baker, Carlos A Monteiro, Christopher Millet, Jean-Claude Moubarac, Patricia Jaime, Neha Khandpur.

This paper presents evidence in support of policies to:

- Reduce intake of ultra-processed foods as well as those high in sugar, salt, and fats.

- Restrict the marketing, availability, and affordability of ultra-processed foods (examples: taxes, warning labels, advertising bans, limits on use in schools, etc).

- Restrict the marketing and political power of transnational food corporations (manufacturers, retailers, fast food chains, agricultural producers).

- Support the production, availability, and affordability of minimally processed foods.

III. POLITICS

Towards unified global action on ultra-processed foods: understanding commercial determinants, countering corporate power, and mobilising a public health response. [Full text here] Phillip Baker, Scott Slater, Mariel White, Benjamin Wood, Alejandra Contreras, Camila Corvalán, Arun Gupta, Karen Hofman, Petronell Kruger, Amos Laar, Mark Lawrence, Mikateko Mafuyeka, Melissa Mialon, Carlos A Monteiro, Silver Nanema, Sirinya Phulkerd, Barry M Popkin, Paulo Serodio, Katherine Shats, Christoffer Van Tulleken, Marion Nestle, Simón Barquera.

This paper describes how the food industry is the main barrier to reducing intake of ultra-processed foods.

Food companies exert political power through corporate political activities, coordinated through a global network of front groups, multi-stakeholder initiatives, and research partners. They:

- Engage in direct lobbying,, infiltrate government agencies, and litigate

- Promote corporate-friendly governance models, forms of regulation, and civil societies

- Frame debate, generate favorable research evidence, and manufacture scientific doubt

To counter such corporate practices, actions are needed to

- Disrupt the ultraprocessed business model

- Redistributing resources to other types of food producers

- Protect food governance from corporate interference

- Implement robust conflict of interest safeguards in policy making, research, and professional practice.

This paper also addresses and responds to criticisms of the ultra-processed concept.

KEY MESSAGE: Reducing production and consumption of ultra-processed foods is a priority global health issue.

Thereore, ultra-processed foods require a global response to:

- Confront corporate power,

- Reclaim public policy space

- Restructure food systems to prioritize health, equity, and sustainability over corporate profit.

No excuses. Get to work!

RESOURCES