Let’s Ask Marion: What’s The Recommended Daily Allowance of Sugar?

Here’s another one of those occasional queries from Kerry Trueman. This one, posted at Huffington, is about FDA regulations for labeling sugars.

Trueman: I’ve just begun to sink my teeth into Michael Moss’s extraordinary food industry exposé, Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us, a book you’ve rightly lauded as a “breathtaking feat of reporting.” As Moss points out, the FDA is happy to give us guidelines on how much salt and fat to include in our daily diets, but–as a glance at any nutritional label shows–they’ve declined to make any recommendation at all about sugar.

Does this mean that:

(a) It’s OK to eat as much sugar as you like, or:

(b) There may be an unsafe level of sugar consumption, but the FDA just doesn’t have the resources to figure out what that level is, or:

(c) The FDA knows how much sugar we can eat without harming our health, but the food industry won’t let them tell us.

How is the average American supposed to interpret this absence of information?

Nestle: Whoa. Slow down. Let’s back up a minute. The FDA sets nutritional standards for food labels, but the Institute of Medicine (IOM) sets nutritional standards for dietary intake. To understand what’s happening with the FDA and food labels, we have to talk about what the IOM used to call the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) but now calls Dietary Reference Intakes (which, confusingly, include RDAs and other standards, such as Upper Limits).

In 2002, the IOM set standards for total carbohydrates–sugars and starches (which are converted to sugars in the body). In its review of the evidence, the IOM set the RDA for total carbohydrates at 130 grams a day (roughly 4 ounces) to meet the needs of the brain for fuel. This amount is much less than typically consumed by adults.

As for sugars, the IOM noted that the average intake of sugars among adolescent males was 143 grams per day, and that the heaviest users were consuming 208 grams per day–much more than the amount of total carbohydrate needed.

Since sugars are not required nutrients, the IOM could not set an RDA. And although it did not have enough evidence to set an Upper Limit, the IOM suggested that the maximum level of intake of added sugars (as opposed to those naturally present in foods) should be a whopping 25% or less of calories.

Americans typically consume around 20% of calories from added sugars. Taken at face value, the IOM suggestion made it sound as if current intake levels were just fine. The sugar industry happily viewed 25% as a recommendation, not a maximum.

Before the sugar industry got after them, many countries recommended an upper level of sugar intake at 10% of calories. That’s what the U.S. Pyramid did in 1992.

The sugar industry does not like the 10% recommendation. It means, for example, that just one of Mayor Bloomberg’s 16-ounce sodas takes care of recommended sugar intake for the day.

Robert Lustig, who is largely concerned about what too much fructose does to us, thinks that 50 grams of sugar (sucrose or HFCS) is a reasonable Upper Limit for most people. This would provide 25 grams of fructose, which the body can handle with relative ease. What’s interesting about his cut point is that it means 200 calories a day, or 10% of calories for a 2000 calorie diet. So there we are at 10% of calories again.

If the FDA wanted to be helpful, it could do two things.

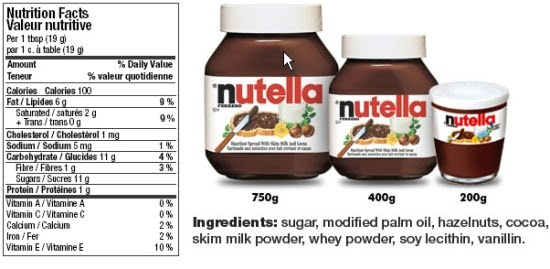

1. Require companies to list added sugars under the carbohydrate category on food labels.

2. Set a DV for sugars at 50 grams.

In the meantime, everyone would be healthier eating less sugar.