A reader in Australia writes that she “just came upon a doozy of an industry-funded paper.”

Title: Sales of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Australia: A Trend Analysis from 1997 to 2018, by William S. Shrapnel and Belinda E. Butcher. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1016; doi:10.3390/nu12041016.

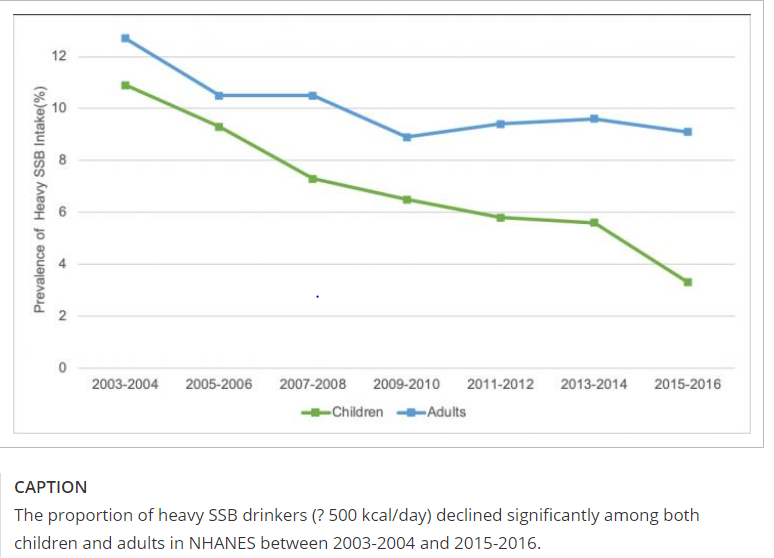

Conclusion: Major, long-term shifts are occurring in the market for non-alcoholic, water-based beverages in Australia, notably a fall in per capita volume sales of SSBs and an increase in volume sales of water. Both trends are consistent with public health nutrition strategies for obesity prevention and suggest that the downward trend in the percentage of dietary energy from added sugars in the Australian diet may be continuing.

Funding and Conflicts of Interest: This analysis was funded by an unrestricted grant from The Australian Beverages Council Ltd. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

So what’s the problem here (besides the usual questions about the accuracy of the “no role” statement)?

The clue comes from an article in Food Navigator Asia: “Not a taxing question: Australian sugar sweetened beverage consumption slumps as obesity rates continue to soar.”

The article quotes a representative of the Beverage Council:

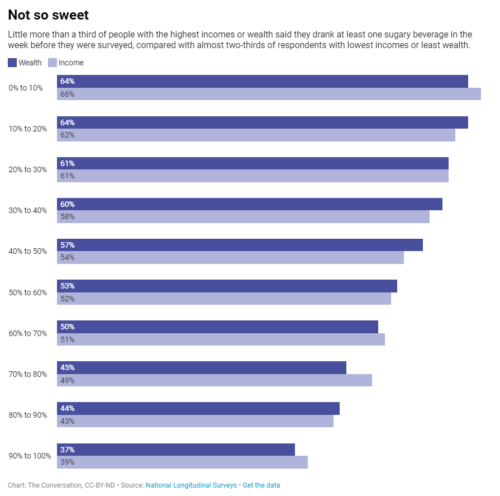

Obesity is multi-factorial, the reason why people become overweight and then obese, is because of the lack of physical activity, a sedentary lifestyle, and also poor diet…a sugar tax alone would not reduce the obesity rates in the country, and was a complex challenge for the government to overcome. The beverage industry is against a sugar tax, and SSB tax. The evidence and science behind the effectiveness of a sugar tax is weak.

Comment: The point of this study is to produce evidence against the value of soda or sugar taxes, even though sodas are still the largest source of sugars in Australian diets, and taxes have been shown to reduce consumption in other countries. When it comes to sugary drinks, less is better.

Just for fun, here’s Healthy Food America’s 2019 map of countries with soda taxes.