Ketchup is a vegetable? Again?

Food Chemical News (FCN) reports today that the USDA has sent its final rules on nutrition standards for school lunches and breakfasts to the Office of Management and Budget for approval. The final content of what got submitted is not known.

These rules, you may recall from previous posts, are based on recommendations of the Institute of Medicine in a 2009 report on School Meals.

Several of the USDA’s proposals for implementing these suggestions have elicited more than the usual level of fuss. The most controversial:

- Limits on starchy vegetables to two servings a week. As I noted a few days ago, the Senate passed an amendment to the USDA’s appropriations bill to block any restrictions on potatoes. Most observers think this means that unlimited potatoes will stay in the school meals.

- Preventing tomato paste on pizza from counting as a vegetable. According to FCN, language in the appropriations bill “also stipulates that tomato paste used to make pizzas can be counted toward the weekly total of vegetable servings.”

Does the Senate think this can pass the laugh test?

Historical note: Remember when the Reagan administration proposed to allow ketchup to count as a vegetable in school meals:

An additional proposed change in crediting policy would allow vegetable and fruit concentrates to be credited on a single-strength reconstituted basis rather than on the basis of the actual volume as served.

For example, one tablespoon of tomato paste could be credited as 1/4 cup single-strength tomato juice. Previously, it was only credited as 1 tablespoon, the volume as served (Federal Register 9-4-81).

Meaning ketchup!

The press had a field day. The ensuing bipartisan hilarity and what Nutrition Action (November 1981) called a “maelstorm of criticism from Congress, the press, and the public alike” induced the USDA to rescind the rules one month later.

- The Washington Post (9-26-81) quoted the budget director’s comment that USDA “not only has egg on its face, but ketchup too.”

- Republican Senator John Heinz (whose company owns Heinz ketchup) said “Ketchup is a condiment. This is one of the most ridiculous regulations I ever heard of, and I suppose I need not add that I know something about ketchup and relish–or did at one time.”

- The New York Times (9-28-81) noted that “Democrats are still chortling at what they hail as ‘the Emperor’s New Condiments’—the attempt to declare ketchup a school-lunch vegetable.”

Times have changed. Senators used to have the health of American school children in mind. Now, they undermine efforts by USDA to improve meals for kids.

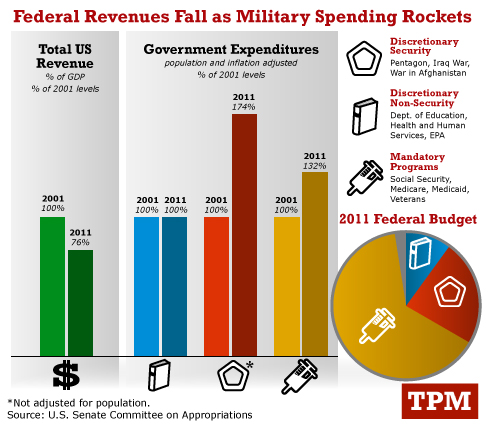

The Senate’s action has nothing to do with public health and everything to do with political posturing and caving in to lobbyists.

The Senate should reconsider its actions. The USDA should not back down on this one.

Additions, November 17: background documents and additional links

- The School Nutrition Association’s summary of its concerns about the USDA’s proposed rules

- The full set of comments from the School Nutrition Association

- A letter from Senator Amy Klobuchar complaining to USDA about the proposed rules