Pet obesity: Like it or not, it’s not going away

I subscribe to Pet Food Industry and greatly admire the superb quality of its reporting.

Here’s an example:

Pet obesity 2023: owners oblivious, vets scared to talk: Pet owners may be largely unaware that there is a problem, especially with their own dogs and cats, despite years of warnings.

Several items in this article got my attention.

A. It is based on a survey by The Association for Pet Obesity (APOP). Pet obesity is such a widespread problem that it has induced formation of a society to address it.

B. Pet owners do not recognize that their pets are overweight.

The survey found only 28% of cat owners and 17% of dog owners to say their pets were overweight. Instead, 84% of dog owners and 70% of cat owners said their pets’ weights were healthy.

Veterinarians say 59% of dogs and 61% of cats are overweight or obese, and percentages are rising.

C. Veterinarians are reluctant to discuss obesity with pet owners.

Although the survey found 84% of veterinarians to report encountering “pet owners who appeared embarrassed or angry when told their pet was overweight,” only 4% of owners thought their veterinarian would be uncomfortable discussing the issue.

Comment

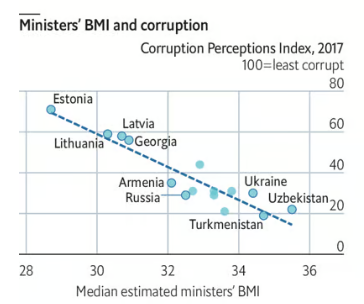

None of this should be surprising, as I think about it. Doctors avoid discussing obesity with human patients (embarrassment, stigma, and lack of time, empathy, or satisfactory treatment approaches). Obesity has become the “O” word.

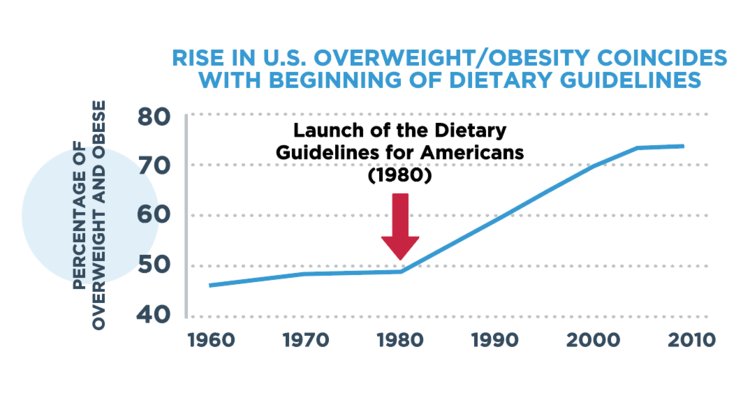

An astonishing 75% of U.S. adults are overweight or obese, and children are also getting there.

We, as a society, need to prevent this kind of weight gain for ourselves, our kids, and our pets.

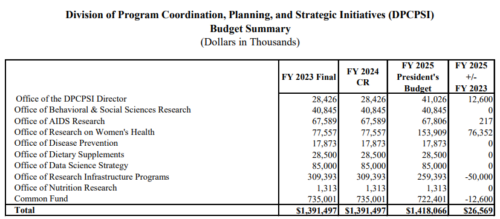

How to do this requires policies, and lots of them, all at once. Policies require politics. Politics requires advocacy.

We need all of these, and right away.

Resources

Sunday’s New York Times has an entire section on pets.

Information about my book with Malden Nesheim on pet food issues, Feed Your Pet Right, is here.