Meat on the agenda: Bacon and Fast Food antibiotics

I’m collecting reports about meat.

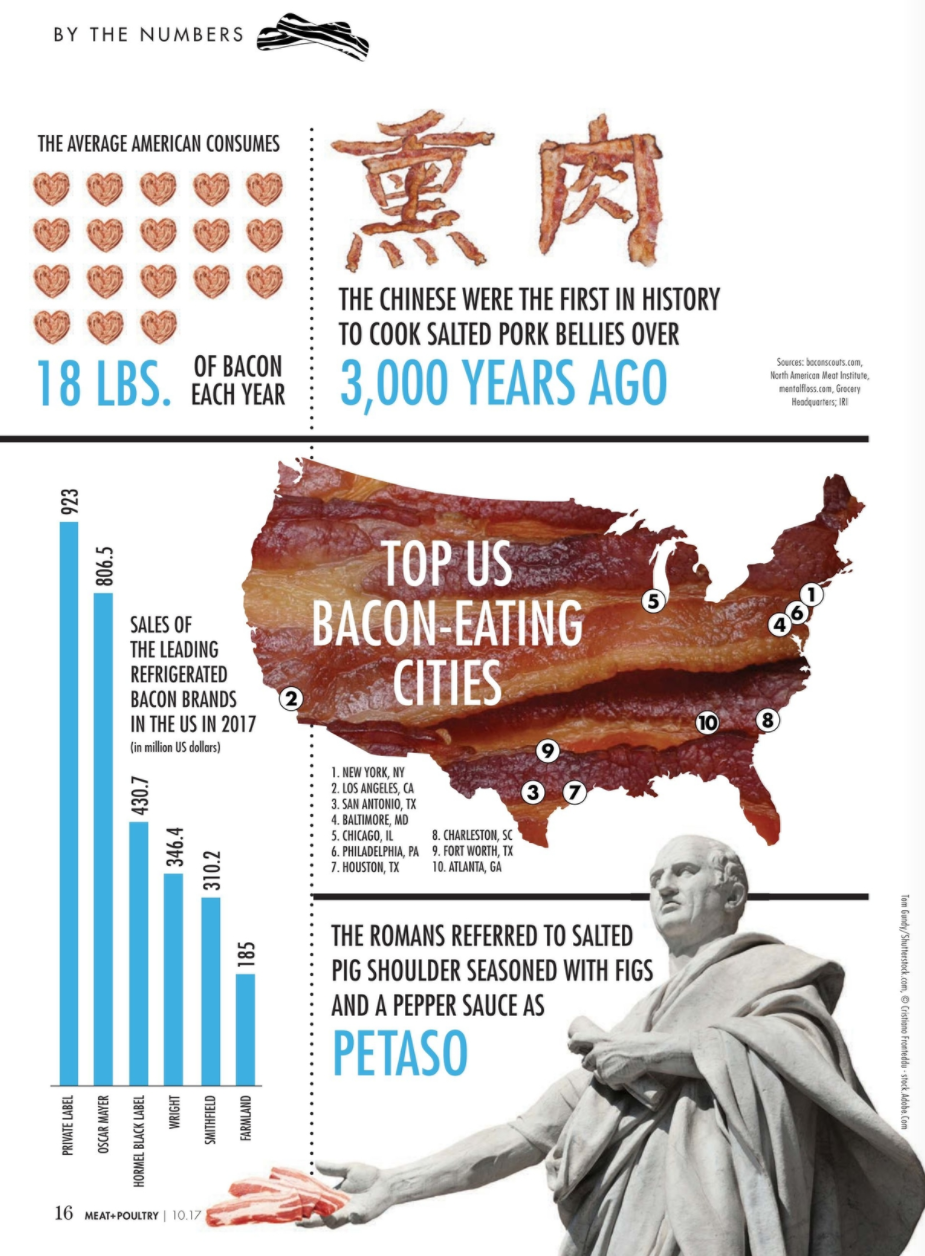

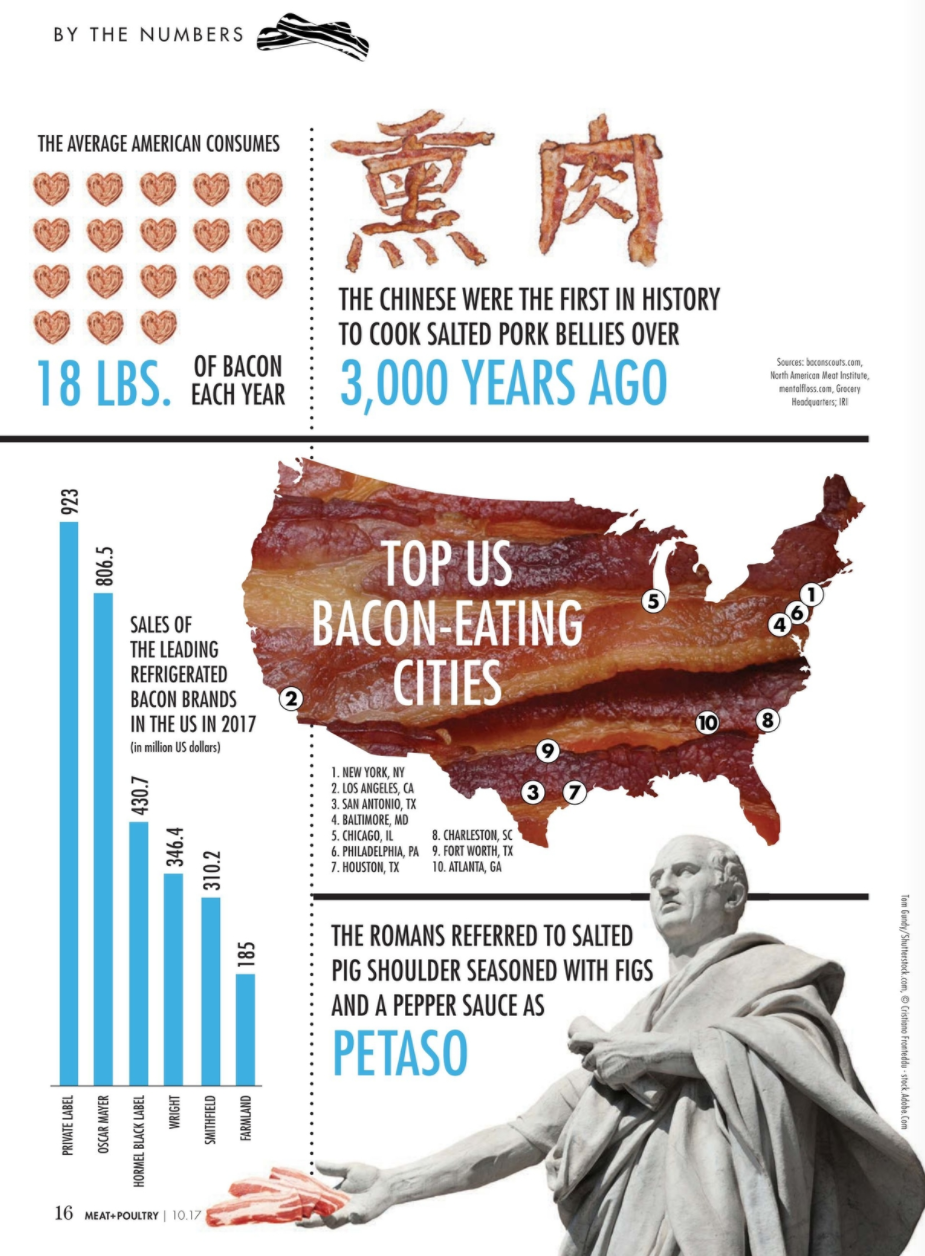

The first is The Bacon Report from MeatPoultry.com.

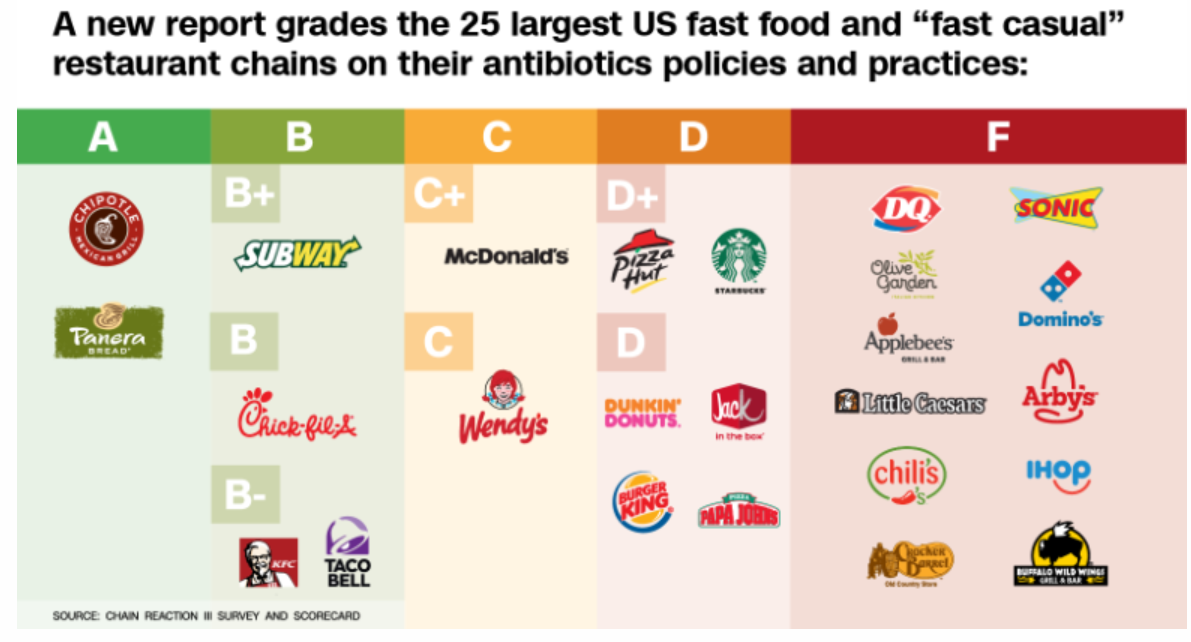

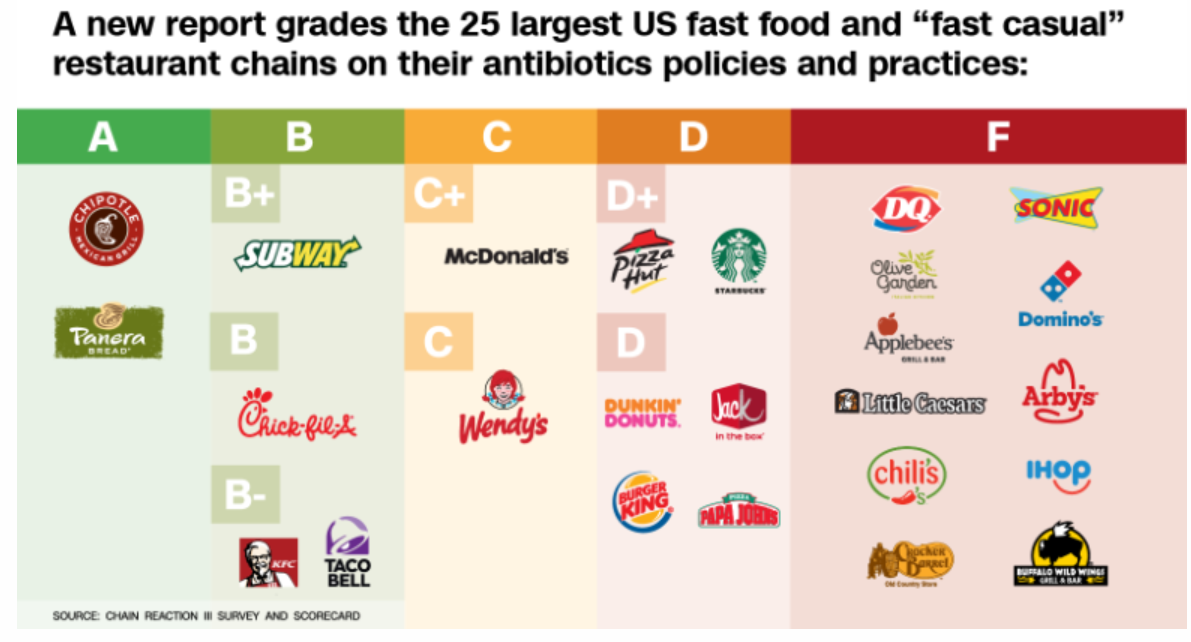

And here’s Restaurant Report Card: What’s in your fast food meat?

I’m collecting reports about meat.

The first is The Bacon Report from MeatPoultry.com.

And here’s Restaurant Report Card: What’s in your fast food meat?

I’ve never understood why people who do not want to eat meat for reasons of health, animal welfare, environmental protection, or religion want to eat meat substitutes when vegetarian and vegan diets can be delicious on their own.

Because one of my food rules is “never eat anything artificial,” meat substitutes are not on my food radar.

Nevertheless, I am fascinated by the intense interest of venture capitalist investors—and many eaters—in plant-based or lab-based concoctions that look and more-or-less taste like meat (I’ve tried as many of them as I can, but find them all too salty).

Global Meat News

The industry newsletter, GlobalMeatNews.com, is a great place to keep up with what’s happening with meat substitutes. From it, I learn:

Impossible Burger

And then, there is the fuss over this lab-based substitute so realistic that it appears to “bleed.” It has had some difficulty with the FDA over the safety of this ingredient.

—Impossible Burger FOIA documents

—On-line searchable database of synthetic biology derived ingredients, including Impossible Food’s “heme”.

–FOE website on the risks of synthetic biology to health and environment.

My opinion (for what it’s worth)

If people would rather eat these things than real meat, that’s fine for them. I’m not concerned about the safety issues; the probability of this protein’s being unsafe seems small.

I will be following this topic with great interest. Stay tuned.

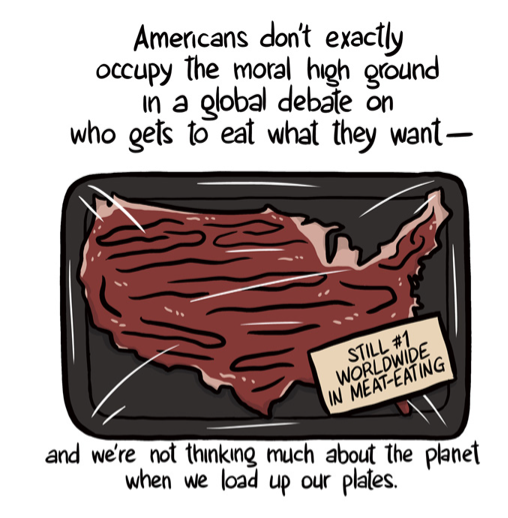

I love Civil Eats’ Infographic explaining the global meat situation. Here’s how it begins. Click on the link to see the rest of it. Definitely worth a look.

Katy has a terrific show on Heritage Radio that I’ve been on several times and I was happy to do a blurb for her new book:

Katy Keiffer has produced a thorough and well researched analysis of everything that’s wrong with industrial meat production. Her book is worth reading for its focus on animal welfare, antibiotic resistance, and worker safety, but even more for its critique of the effects of animal feed production on international trade and land grabs. This book is for everyone who cares about how meat-eating affects our planet.

Global Meat News is another one of those industry newsletters I follow closely. It’s been tracking what’s been happening with meat in Brazil. This is a great place to find out about this quickly.

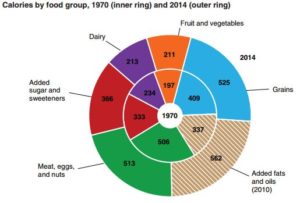

The USDA has just issued a report on trends in per capita food availability from 1970 to 2014.

Here’s my favorite figure:

The inner ring represents calories from those food groups in 1970. The outer ring includes data from 2014.

The bottom line: calories from all food groups increased, fats and oils and the meat group most of all, dairy and fruits and vegetables the least.

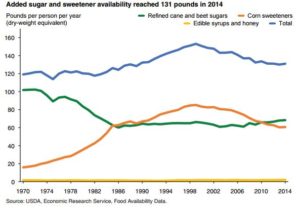

The sugar data are also interesting:

Total sugars (blue) peaked at about 1999 in parallel with high fructose corn syrup (orange). Table sugar, sucrose, has been flat since the 1980s (green).

Eat your veggies!

Marta Zaraska. Meathooked: The History and Science of Our 2.5-Million-Year Obsession with Meat. Basic Books, 2016.

If this were just another diatribe against meat-eating, I would not have bothered to read it but this book is much more interesting than that. The Polish-Canadian journalist Marta Zaraska describes herself as a “sloppy vegetarian,” someone who doesn’t eat much meat but

can’t seem to completely let go of meat either. There is something in it—in its cultural, historic, and social appeal, or maybe in its chemical composition—that keeps luring me back.

And that’s what this book is about: the cultural, historic, and social (and maybe even the chemical) appeal of eating meat. Zaraska identifies the reasons—the hooks—of this appeal, linked as they are to genetics, culture, history, and the politics of the meat industry and government.

Although Zaraska clearly thinks eating less meat would be good for health, animal welfare, and the environment, that’s not really the book’s goal. Instead, it’s to understand why most people don’t want to be vegetarian, let alone vegan, and why even small steps in that direction are worth taking.

What’s impressive about this book is the friendliness, human understanding, and charm of its writing, and the global scope of the interviews on which it draws (full disclosure: it briefly quotes my work).

A couple of scientific points didn’t ring right (beans do have methionine, just not as much as is needed), and I’m not sure that mock meats, meat substitutes, and edible insects will satisfy the “hooks” she describes so well, but these are minor quibbles.

Thanks to a reader for sending these items from a journal that I don’t usually come across. These bring the casually collected total since last March to 145 studies favorable to the sponsor versus 12 that are not.

Consuming the daily recommended amounts of dairy products would reduce the prevalence of inadequate micronutrient intakes in the United States: diet modeling study based on NHANES 2007–2010. Erin E Quann, Victor L Fulgoni III and Nancy Auestad. Nutrition Journal 2015; 14:90 DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-0057-5

Association of lunch meat consumption with nutrient intake, diet quality and health risk factors in U.S. children and adults: NHANES 2007–201Sanjiv Agarwal, Victor L. Fulgoni III and Eric P. Berg. Nutrition Journal. 2015;14:128. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-011f8-9

A review and meta-analysis of prospective studies of red and processed meat, meat cooking methods, heme iron, heterocyclic amines and prostate cancer. Lauren C. Bylsma and Dominik D. Alexander. Nutrition Journal. 2015;14:125. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-0111-3

Are restrictive guidelines for added sugars science based? Jennifer Erickson and Joanne Slavin. Nutrition Journal. 2015;14:124. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-015-0114-0

Cow’s milk-based beverage consumption in 1- to 4-year-olds and allergic manifestations: an RCT. M. V. Pontes, T. C. M. Ribeiro, H. Ribeiro, A. P. de Mattos, I. R. Almeida, V. M. Leal, G. N. Cabral, S. Stolz, W. Zhuang and D. M. F. Scalabrin. Nutrition Journal. 2016;15:19. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-016-0138-0

Whole grain consumption trends and associations with body weight measures in the United States: results from the cross sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2012. Ann M. Albertson, Marla Reicks, Nandan Joshi and Carolyn K. Gugger. Nutrition Journal 2016;15:8. DOI: 10.1186/s12937-016-0126-4