Here is the online version of my commentary in New Scientist, March 14, 2015:24-25.

I submitted an illustration with it, which the editors did not use. It’s from the Ontario Medical Association.

Cigarettes get plain packets – will junk food be next?

The tobacco industry is fighting moves to sell cigarettes in plain packs by claiming food manufacturers will be hit next. Will they?

ANTI-SMOKING advocates will be delighted. MPs have today voted in favour of introducing uniform packaging for cigarettes in the UK. That plain wrappers will undoubtedly further reduce smoking, especially among young people, is best confirmed by the tobacco industry’s vast opposition to this government measure and positive evidence from Australia, the first country to adopt it.

Along with lobbying and appeals to the World Trade Organization, the tobacco industry, when under attack, inevitably wheels out well-worn arguments about the nanny state, personal freedom, lack of scientific substantiation, and losses in jobs and tax revenues.

So to perk up its tired and thoroughly discredited campaign, the tobacco folks have added a new argument. Requiring plain wrappers on cigarettes, they say, is a slippery slope: next will be alcohol, sugary drinks and fast food. This argument immediately raises questions. Is it serious or just a red herring? Should the public health community lobby for plain wrappers to promote healthier food choices, or just dismiss it as another tobacco industry scare tactic?

Let me state from the outset that foods cannot be subject to the same level of regulatory intervention as cigarettes. The public health objective for tobacco is to end its use. So for cigarettes the rationale for plain wrappers is well established. Company logos, attractive images, descriptive statements, package colours and key words all promote purchases. Plain wrappers discourage buying, especially along with other measures such as bans on advertising, smoke-free policies, taxes and health warnings.

Australia’s pioneering law specified precise details of pack design, warning images and statements. The result: cigarette brands all look much alike. Most reports say plain packaging boosts negative perceptions of cigarettes among smokers and increases their desire to quit. Australia expects plain packaging to further reduce its smoking rate, which, at 12.8 per cent, is already among the world’s lowest. Along with the UK, New Zealand and Ireland are well on the way to adding plain packaging to their anti-smoking arsenal. More nations are considering it.

Which is all bad news for the tobacco industry. So it ramps up the slippery slope argument, hoping the food industry will support its fight against plain wrappers. It cites examples such as the regulation of infant formula in South Africa, where pictures of babies on labels are forbidden; that’s a big problem for the Gerber food brand – Gerber’s company logo is a smiling baby.

But those peddling the slippery slope idea ignore the fact that the health message for tobacco is simple: stop smoking. But beyond tobacco, it is more complex. For alcohol it is a little more nuanced: drink moderately, if at all. For food it is much more nuanced. Food is not optional; we must eat to live. Nutritional quality varies widely. Foods are spread across a spectrum from unhealthy to healthy, from soft drinks (no nutrients) to carrots or fish (many nutrients). Most fall somewhere in between. What’s more, an occasional soft drink is fine; daily guzzling is not. So the advice is to choose the healthy and avoid or eat less junk, both in the context of calorie intake and expenditure.

Is there any evidence that plain packaging for unhealthy foods would reduce demand? Research has focused on marketing’s effect on children’s food preferences, demands and consumption. Brands and packages sell foods and drinks, and even very young children recognise and desire popular brands. When researchers compare the responses of children to the same foods wrapped in plain paper or in wrappers with company logos, bright colours or cartoon characters, kids invariably prefer the more exciting packaging.

But the problem is deciding which foods and beverages might call for plain wrappers. For anything but soft drinks and confectionery, the decisions look too vexing. Rather than having to deal with such difficulties, health advocates prefer to focus on interventions that are easier to justify – scientifically and politically.

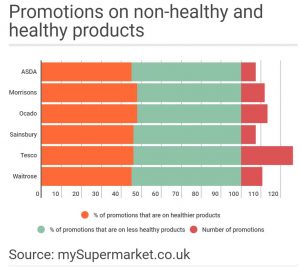

We know that some regulations and market interventions –analogous to, if not the same as those aimed at smoking cessation – are essential for reducing the damage from harmful products. If not plain packaging, then what? Studies suggest small benefits from a long list of interventions such as taxes, caps on portion size, front-of-package traffic-light labels, nutrition standards for school meals, advertising restrictions, and elimination of toys from fast food meals and cartoons from packaging. Rather than dealing with the impossible politics of plain wrappers on foods, health advocates increasingly favour warning labels.

These first appeared on cigarette packs in the 1960s and have been considered for food products since the early 1990s. Heart disease researchers suggested that foods high in calories and fat should display labels such as: “The fat content of this food may contribute to heart disease.” More recently, health advocates in California and New York proposed warning labels on sugary drinks. The Ontario Medical Association takes a similar view: “To stop the obesity crisis, governments must apply the lessons learned from successful anti-tobacco campaigns.” It has mocked up examples of warnings on foods.

Although no warning label law has passed so far, such messages are the logical next step in promoting healthy food choices, in the same way that plain wrappers are the next logical step for all cigarette packages. Health advocates should recognise the slippery slope argument for the typical tobacco ploy that it is.