I keep getting questions about saturated fat. Does it really pose a health risk? If so, how serious a risk? And isn’t eating real food OK even if it contains saturated fat? Good questions. Here are a couple of recent examples:

Reader #1: I think that the idea that saturated fats in meat and dairy are unhealthful is errant, based on correlative – not causative – scientific studies…I propose that instead of demonizing one nutrient over another, we favor whole, high-quality foods of both animal and plant origin…designed by nature (and thousands of years of trial and error) to meet the needs of their respective populations. What do you say?

Reader #2: I wonder how the government can be so focused on low-fat milk. Is that really such a huge problem? Isn’t the bigger problem that the state of NY is telling people pretzels make a healthy snack? Isn’t it soda and cheese doodles and eating every dinner from a box that is the problem? Whole milk, really? I’d appreciate your clarity on this… we are full fat milk and cheese people, and all of this perplexes me.

I can understand why anyone might be confused about saturated fat. Food fats are complicated and it helps to be a biochemist (as I once was) to sort out the issues related to degree of saturation and whether the omegas are 3, 6, or 9 (I explain all this in the chapter on fats and in an appendix to What to Eat).

And yes, the science is complex and sometimes seems contradictory but scientific committees for the past 50 years have concluded one after another that substituting other kinds of fatty acids for saturated fatty acids would reduce levels of blood cholesterol and the risk for coronary heart disease.

And no, those scientists cannot have all be delusional or paid off by the meat or dairy industries. They—like scientists today—mostly call the science the way they see it.

What makes the research especially hard to sort out is that all food fats—no exceptions—are mixtures of saturated, unsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (just the proportions differ), that some saturated fatty acids raise blood cholesterol levels more than others do, and that one kind—stearic acid—seems neutral with respect to blood cholesterol.

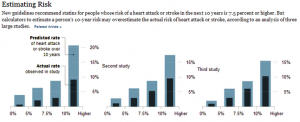

But overall, the vast majority of expert committees typically conclude that we would reduce our heart disease risks if we kept intake of saturated fat below 10% of calories, and preferably at or below 7%. On average, Americans consume 11-12% of calories from saturated fat, which doesn’t sound too far off but the average means that many people consume much more.

As is often the case with studies of single nutrients, research sometimes comes to different conclusions. Several studies—all quite well done—have appeared just in the last year or so.

One of these is a meta-analysis (a review of multiple studies). It concludes:

…there is no significant evidence for concluding that dietary saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of CHD [coronary heart disease] or CVD [cardiovascular disease]. More data are needed to elucidate whether CVD risks are likely to be influenced by the specific nutrients used to replace saturated fat [my emphasis].

What saturated fat gets replaced with is the subject of three other well conducted studies that come to a different—the mainstream—conclusion. One, another recent meta-analysis, confirms decades of previous observations (sorry about the annoying abbreviations):

These findings provide evidence that consuming PUFA [polyunsaturated fatty acids] in place of SFA [saturated fatty acids] reduces CHD events in RCTs [randomized clinical trials]. This suggests that rather than trying to lower PUFA consumption, a shift toward greater population PUFA consumption in place of SFA would significantly reduce rates of CHD.

Translation: replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats would be healthier.

Another meta-analysis comes to the same conclusion:

The associations suggest that replacing SFAs with PUFAs rather than MUFAs [monounsaturated fatty acids] or carbohydrates prevents CHD over a wide range of intakes.

A very recent consensus statement concludes:

the evidence from epidemiologic, clinical, and mechanistic studies is consistent in finding that the risk of CHD is reduced when SFAs are replaced with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). In populations who consume a Western diet, the replacement of 1% of energy from SFAs with PUFAs lowers LDL cholesterol [the “bad” kind] and is likely to produce a reduction in CHD incidence of ≥2–3%. No clear benefit of substituting carbohydrates for SFAs has been shown, although there might be a benefit if the carbohydrate is unrefined and has a low glycemic index.

The advisory committee to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans reviewed this and other research relating saturated fatty acids to heart disease risk and concluded:

Cholesterol-raising SFAs, considered SFA minus stearic acid…down-regulate the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor by increasing intracellular cholesterol pools and decreasing LDL cholesterol uptake by the liver.

The committee’s research review addressed the question, “What is the Effect of Saturated Fat Intake on Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Disease or Type 2 Diabetes, Including Effects on Intermediate Markers such as Serum Lipid and Lipoprotein Levels?” It judged the evidence strong

that intake of dietary SFA is positively associated with intermediate markers and end point health outcomes for two distinct metabolic pathways:

1) increased serum total and LDL cholesterol and increased risk of CVD and

2) increased markers of insulin resistance and increased risk of T2D [type-2 diabetes]. Conversely, decreased SFA intake improves measures of both CVD and T2D risk.

The evidence shows that 5 percent energy decrease in SFA, replaced by MUFA or PUFA, decreases risk of CVD and T2D in healthy adults and improves insulin responsiveness in insulin resistant and T2D individuals.

How much saturated fat might increase the risk of heart disease or type-2 diabetes depends on how much you eat as well as what you eat.

What to do to reduce your dietary risks for heart disease? Take a look at the top 15 sources of saturated fats in U.S. diets:

- Regular cheese

- Pizza

- Grain-based desserts (cakes, cookies, pies, pop-tarts, donuts, etc)

- Dairy desserts

- Chicken and chicken mixed dishes (e.g. fingers)

- Sausage, franks, bacon, and ribs

- Burgers

- Mexican mixed dishes

- Beef and beef mixed dishes

- Reduced fat (not skim) milk

- Pasta and pasta dishes

- Whole milk

- Eggs and egg mixed dishes

- Candy

- Butter

- Potato/corn/other chips

- Nuts/seeds and nut/seed mixed dishes

- Fried white potatoes

Explanation: These foods do not necessarily have the most saturated fat. If the list surprises you, recall that all food fats have some saturated fats. These foods are leading sources because they contain some saturated fat and many Americans eat them.

It is surely no coincidence that these foods are also among the leading sources of calories in U.S. diets. The health effects of diets, let me repeat, have to do with quantity as well as quality.

If you do not habitually eat most of the foods on this list, and are not gaining weight, saturated fatty acids are much less likely to be a problem for you.

And just because saturated fats raise the risk of heart disease does not mean they are poisons. Eat fats. Just not too much.