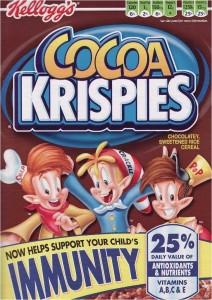

Q: It’s great that San Francisco City Attorney Dennis Herrera put a stop to the absurd “immunity” claim on Kellogg’s Cocoa Krispies, but how do companies get away with this?

A: I confess; I’m a health-claims junkie. I snatched up the immunity-claiming box of Cocoa Krispies the minute I saw it in a supermarket last August. I consider it a treasure: “Now helps support your child’s IMMUNITY.”

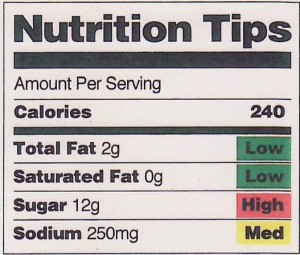

How does Cocoa Krispies perform this miracle? The cereal contains 25 percent of the daily value of antioxidant vitamins A, B, C and E per serving instead of the old 10 percent. Vitamins, Kellogg points out, play an important role in immunity.

Of course they do. All nutrients are involved in immune function. But is it remotely possible that Cocoa Krispies might protect your child against colds or swine flu? I wish.

Antioxidants present an unparalleled marketing opportunity. Kellogg does not have to prove that its cereals are protective. Immunity claims fall into a Food and Drug Administration regulatory gray area. “Supports immunity” is a “structure-function” claim, so called because it promises to support a structure or function of the human body. However you might interpret such claims, they do not really promise to prevent, treat or cure disease.

Congress expressly authorized structure-function claims when it deregulated dietary supplements in 1994. But that law did not apply to foods. Food companies wanted to use these claims, too. At first the FDA balked. When faced with further legislation and court overturns, the FDA gave up. Now it merely says that structure-function claims on supplements must be truthful and not misleading. The FDA says nothing about structure-function claims on food products. It mostly looks away when they appear.

“Misleading” is inevitably in the eye of the beholder. Herrera turns out to be a skeptic.

“The Immunity claims,” he said, “may falsely suggest to parents that cereals like Cocoa Krispies are more healthy for their children than other breakfast foods … [and] mislead parents into believing that serving this sugary cereal will actually boost their child’s immunity.” Kellogg, he said, must produce the evidence or have the claim subject to “immediate termination or modification.”

Faced with this threat and with ridicule in the press, Kellogg wisely decided to phase out the immunity-labeled Cocoa Krispies packages. Consider them collectors’ items.

Much is at stake. Ready-to-eat cereals produce more than $8 billion a year in sales. Kellogg spent about $32 million in 2008 to promote Rice Krispies cereals, and $4 million of that amount went to advertise Cocoa Krispies alone.

Shoppers care about health. If cereals can be advertised with special health benefits, more boxes will fly off the shelves. Food companies consider health claims essential for marketing their products.

This explains why so many companies are adding omega-3 fats, probiotics and antioxidants to so many foods. These ingredients make foods “functional,” meaning that the foods contain something beyond their usual nutritional value. Although little evidence shows that functional foods make healthy people healthier, companies can use functional ingredients to make health claims, no matter how far-fetched. These days, functional foods are about the only processed foods with increasing sales.

Kellogg has plenty of company with functional ingredients and health claims. See, for example, the claims on Nestlé (no relation) Juicy Juice products targeted to toddlers. One product adds antioxidants to “help support immunity.” The other adds omega-3s to “aid brain development.”

Think about it: Will feeding your toddler a sugary juice product really make her smarter? Face it. You are not supposed to think about it. You are supposed to buy – and feel good about doing so.

Absent the FDA, Herrera stepped into the breach. He does not care whether the claims are on Kellogg cereals or Juicy Juice cartons. If companies make such claims, he insists that they produce the evidence for them.

This will not be easy to do. It is one thing to find evidence that specific nutrients are involved in immune function. It is quite another to show that people who eat sweetened cereals or juices containing such nutrients are healthier than those who do not.

That is why the European Food Standards Agency denied hundreds of company petitions for health claims. The agency cannot find much evidence for the health benefits of foods with added functional ingredients. Its decisions have put European food marketers into crisis. How are they supposed to sell products without health claims?

As I keep saying, health claims are about marketing, not health. If it were up to me, I would remove all health claims from food packages. Foods are not drugs. Health claims cannot help but mislead.

So let’s congratulate Herrera for filling a regulatory gap. His colleagues – and the press – are doing their job on this one. FDA: Get to work!