Has Mars joined the food movement?

Mars, the very same company that has been trying for years to position chocolate as a health food, appears to be joining the food movement, and big time.

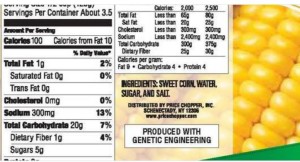

Take a look at its GMO disclosure statement on the back of this package of M&Ms.

If it’s too small to read, the statement is in between MARS and the green Facts Up Front labels)

PARTIALLY PRODUCED WITH

GENETIC ENGINEERING

And this is before Vermont’s GMO labeling rules come into effect in July.

Mars also has come out in support of the FDA’s proposals on voluntary sodium reduction. The company explains that through its “new global Health and Wellbeing Ambition,

Mars Food will help consumers differentiate and choose between “everyday” and “occasional” options. To maintain the authentic nature of the recipe, some Mars Food products are higher in salt, added sugar or fat. As these products are not intended to be eaten daily, Mars Food will provide guidance to consumers on-pack and on its website regarding how often these meal offerings should be consumed within a balanced diet. The Mars Food website will be updated within the next few months with a list of “occasional” products – those to be enjoyed once per week – and a list of “everyday” products – including those to be reformulated over the next five years to reduce sodium, sugar, or fat.

Last year, the company supported the FDA’s proposal to require added sugars labeling with a Daily Value percentage on the Nutrition Facts panel.

It also said it would stop using artificial dyes in its candies.

How to interpret these actions? I’m guessing they mean that the movement for good, clean, fair food has gained enough traction to put long-established food brands on notice: make your products healthier for people and the environment, or else.

Americans these days don’t want artificial and unsustainably produced ingredients in the food they buy and eat. For the makers of highly processed foods – ultraprocessed in today’s terminology – there isn’t a lot that they can do to make the products appear fresh and natural.

But Campbell’s is certainly trying. A few months after announcing that it will phase out genetically modified organisms (GMOs), the iconic soup company said on Friday that it will remove Bisphenol-A (BPA) from its cans by next year.

BPA, you will recall, is a chemical typically used in polycarbonate plastic containers and in the epoxy linings of food cans. It’s also an endocrine disrupter, which means it can interfere with the work our hormones are doing. Some research finds BPA to have effects on childhood development and reproduction.

Although the FDA doesn’t believe evidence of potential harm is sufficient to ban BPA from the food supply, the agency discourages use of BPA-polycarbonate or epoxy resins in baby bottles, sippy cups or packaging for infant formulas. For the past year or so, other retailers have been working hard to phase out BPA and to reassure customers that their cans and packages are safe.

All of these companies sell highly processed foods in an era when the public is demanding – and voting with their dollars – for fresh, natural, organic, locally grown and sustainably produced ingredients.

They can’t provide those things, but they can tout the bad, or unpopular, things that aren’t part of their product, the “no’s”: no unnatural additives, no artificial colors or flavors, no high fructose corn syrup, no trans fat, no gluten and, yes, no GMOs or BPA.

Let me add something about companies labeling their products GMO-free. In my view, the food biotechnology industry created this market – and greatly promoted the market for organics, which do not allow GMOs – by refusing to label which of its products contain GMOs and getting the FDA to go along with that decision. Whether or not GMOs are harmful, transparency in food marketing is hugely important to increasing segments of the public. People don’t trust the food industry to act in the public interest; transparency increases trust.

Vermont voted last year to mandate GMO labeling in the state – the US Senate rejected a bill in mid-March attempting to undermine it – and food conglomerates such as Campbell’s, General Mills, ConAgra, Kellogg and Mars have committed to labeling their products as containing GMO.

In addition to removing BPA from packaging and GMO from products, at least 11 other companies have announced recently that say they are phasing out as many artificial additives as possible, as quickly as they can.

Taco Bell, for example, will get rid of Yellow Dye #6, high fructose corn syrup, palm oil and artificial preservatives, and replace them with “natural” ingredients. Huge food companies such as Kraft, Nestlé (no relation) and General Mills are heading in the same direction.

All this may well benefit consumers to an extent. It also makes perfect sense from a business perspective: the “no’s” sell. But what everyone needs to remember is that foods labeled “free from” still have calories and may well contain excessive salt and sugars. The healthiest diets contain vegetables and lots of other relatively unprocessed foods. No amount of subtraction from highly processed foods is going to change that.