Coca-Cola, which bought Odwalla juices in 2001, is discontinuing the brand and getting rid of 300 jobs and 230 trucks.

Why? People aren’t buying it: too much sugar, and too much competition.

This is the end of a long saga. Odwalla started out selling unpasteurized juices and was doing fine until it got too big.

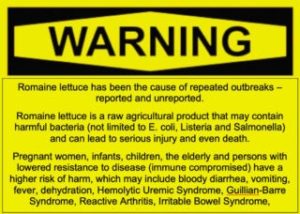

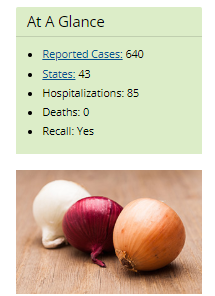

Against company policy, it used apples that had fallen on the ground to make apple juice. Some were contaminated with E. coli O157:H7, which carried a shiga toxin that caused illnesses and deaths. In 1998:

Odwalla, based in Half Moon Bay, Calif., pleaded guilty to 16 counts of unknowingly delivering ”adulterated food products for introduction into interstate commerce” in the October 1996 outbreak, in which a batch of its juice infected with the toxic bacteria E. coli O157:H7 sickened people in Colorado, California, Washington and Canada. Fourteen children developed a life-threatening disease that ravages kidneys.

Odwalla paid a $1.5 million fine and was put on probation. Coca-Cola bought the company anyway.

Food safety lawyer Bill Marler, who represented some of the victims, some of whom have lifelong complications, says Good riddance to bad rubbish.

During the course of the litigation, we uncovered that Odwalla had attempted to sell its juice in 1996 to the U.S. Army – no, not as a biological weapon – but to be sold in base grocery stores to our men and women service members and their families. The Army rejected the product – because it was not fit for military consumers.

His post includes the Army’s letter of rejection: “We determined that your plant sanitation program does not adequatel assure product whoolesomeness for military consumers.”

It also includes some emails suggesting that Odwalla did not want to test for pathogens because they might find some: “IF THE DATA is bad, what do we do about it. Once you create a body of data, it is subpoenable.”

I wrote about the Odwalla events in my book, Safe Food.

The Odwalla outbreak provided convincing proof that unpasteurized and uncooked “natural” foods could contain the same pathogens as meat and poultry if they had the bad luck to come in contact with contaminated animal manure or meat. For the industry, the lessons were mixed. If food companies failed to reduce pathogens, their liability costs could be substantial–in money, time, legal penalties, and reputation—but these problems could be temporary and soon overcome (p. 99).

The end of a saga, indeed.

How’s that for reassuring?

How’s that for reassuring?