Infant formula: what’s the shortage really about?

The White House says it is taking steps to alleviate the nationwide shortage of infant formula.

House speaker Nancy Pelosi has written a letter to democrats demanding action.

Nationwide shortage of infant formula?

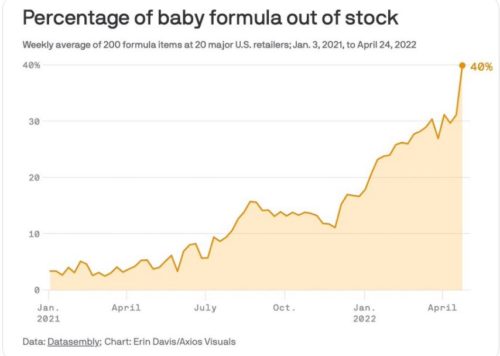

At retailers across the U.S., 40% of the top-selling baby formula products were out of stock as of the week ending April 24…Prices of baby formula, which three-quarters of babies in the U.S. receive within their first six months, have also spiked…Supply-chain snarls related to COVID-19 are contributing to the shortage of formula around the U.S. They include manufacturers having more difficulty procuring key ingredients, packaging hangups and labor shortages…In addition, a major baby formula recall in January exacerbated shortages.

I wrote about the Abbott recall earlier, on February 22 and March 8.

Politico’s Helena Bottemiller Evich has been following this story closely in Politico. You can find her articles here.

Her writing is getting action.

For example, Representative Rosa deLauro released a whistleblower report warning about food safety concerns months before infants died and the FDA investigated.

Food safety lawyer Bill Marler posted a link to the redacted whistleblower report.

He says: Mr. Abbott, you are going to jail for manufacturing tainted infant formula.

The legal jargon aside, if you are a producer of food and knowingly or not manufacturer and sell adulterated food, you can (and should) face fines and jail time. For Abbott, at least 4 kids were sickened and of those two died, from drinking infant formula.

Here is the most recent inspection report at the plant – APPLIED – FOI II – BR Abbott Nutritions- FEI# 1815692 9-2021 EIR.

In the meantime, Bottemiller Evich keeps the focus on how hard this situation is for parents of infants with special nutritional needs. She also has a Twitter thread on this “slow-moving train wreck.” She reproduces this graphic from @erindataviz/@datasembly:

The Seattle Times has a particularly useful guide to what to do—and what not to do—if you can’t find the formula you need.

As to what this is really about, see:

The Morning. This New York Times column attributes this particular shortage to general shortages, monopoly concentration in the formula business, bureaucratic inflexibility, and, most of all, American gerontocracy and overall indifference to the welfare of young children.

A blogger about the politics of monopoly, Matt Stoller, expands on these themes: baby formula monopoly, FDA collusion, and USDA’s methods for dealing with infant formula in the WIC program (this last alone is reason to read this piece). In response, the USDA says it is granting states flexibility in apply the WIC rules.

And the Cato Institute has an informative piece on trade restrictions that prevent import of formula from other countries, including the European Union; this pieces also discusses the WIC problem (Government is major buyer; Abbott is major supplier).

Comment: This is a really bad situation that is finally starting to get attention. Babies are completely dependent on infant formula if they are not being breastfed. It needs to contain all the right nutrients, but it also needs to be safe.

The FDA says it is taking steps to alleviate the formulat shortage.

Why hasn’t it acted more swiftly? Perhaps because of what Bottemiller Evich wrote about previously? See The FDA’s Food Failure.

Basically, we are seeing the results of unregulated monopolies and captured government. With the most vulnerable members of society—and society’s future—at risk.

Additional links

- Letter from 8 Senators headed by Cory Booker to USDA Secretary Vilsack calling for greater formula competition

- Letter from USDA Secretary Vilsack calling on Abbott to provide rebates for competitive formula

- Politico: Senator Tammy Duckworth calls on the FTC to examine lack of competition in the formula market

- Center for Science in the Public Interest urges policymakers in Washington to deploy additional tools

- Congressional subcommittee to investigate shortages

- Background Press Call by Senior Administration Officials to Address Infant Formula Shortage

- Readout of President Biden’s Virtual Meetings with Retailers and Infant Formula Manufacturers

- Associated Press — Parents swap, sell baby formula

- The New York Times — What Parents Need to Know

- USDA’s Q and A page about options for exchanging Abbott formula for other kinds

- USDA’s page on the Abbott recall

- USDA’s guidance for keeping infants safe in the midst of formula shortages

- FDA’s details on Abbott product recalls

- CDC’s report on its Cronobacter investigations, now closed

- Wall Street Journal: What caused the baby formula shortage?

- Bill Marler: Abbott caused the infant formula crisi, but the FDA and public health enabled it

- Abbott and FDA agree on pathway to opening Sturgis MI plant

- Abbott denies its formulas were responsible in an 11-tweet Twitter thread

Additional links that came later

- The Washington Post – Biden invokes Defense Production Act to boost baby formula supply

- WhiteHouse.gov – Letter from President Biden to Secretary Xavier Becerra and Secretary Thomas Vilsack on addressing infant formula shortage

- Fact sheet: President Biden announces new actions to address infant formula shortage

- Memorandum on the delegation of authority under the Defense Production Act to ensure an adequate supply of infant formula