Daily Harvest is a company that makes vegan meals, mostly organic, and freezes them for home delivery.

By mid-June, it had received 470 complaints from customers who ate a new product, French Lentil + Leek Crumbles, but developed severe liver and gall bladder problems. On June 23, Daily Harvest issued a recall of the product “due to potential health risk” (also see After 470 reports of illnesses, Daily Harvest recalls French Lentil + Leek Crumbles).

I was especially interested in this event for two reasons: Daily Harvest twice sent me meals to sample (before it introduced this one) and I knew they had to be cooked before eating, which would kill harmful microbes, and I could not imagine what could possibly cause reactions this toxic (as I explained to the New York Times).

This product’s ingredient list seems benign:

organic butternut squash, organic hemp seeds, organic cauliflower rice, organic extra virgin olive oil, organic french lentils, organic red lentils, organic tri-colored quinoa, organic cremini mushrooms, organic tara flour, organic leeks, organic parsley, water, organic cassava root flour, organic flax seeds, organic sacha inchi powder, chia seeds, organic porcini powder, himalayan sea salt, organic apple cider vinegar, organic onion powder, nutritional yeast, organic garlic powder, organic tomato powder, organic white pepper, organic coriander seeds, organic mustard powder, organic thyme.

More than that, on June 25, food safety lawyer Bill Marler was asking the same question: What is it in Daily Harvest’s French Lentil and Leek Crumbles that is causing liver failure? He was sending samples out to his own labs.

On June 28, Daily Harvest responds to customers sickened, hospitalized from 1 of its products.

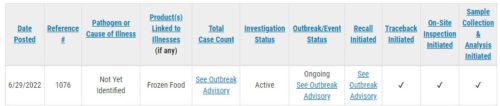

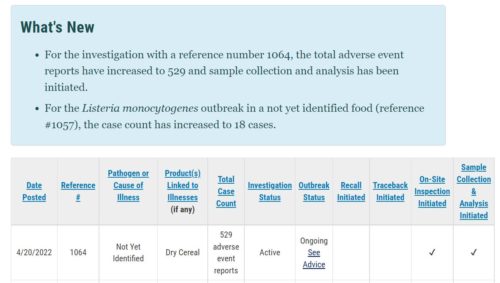

On June 30, the FDA published its Investigation of Adverse Event Reports: French Lentil & Leek Crumbles

On June 17, 2022, in response to consumer complaints submitted to the company, Daily Harvest voluntarily initiated a recall of their French Lentil & Leek Crumbles…From April 28 to June 17, 2022, approximately 28,000 units of the recalled product were distributed to consumers in the continental United States through online sales and direct delivery, as well as through retail sales at the Daily Harvest store in Chicago, IL, and a “pop-up” store in Los Angeles, CA. Samples were also provided to a small number of consumers. Daily Harvest emailed consumers who were shipped the affected product, and other consumers for whom the company had contact information and consumers were issued a credit for the recalled product. Consumers who may still have the recalled product in their freezers should immediately dispose of it.

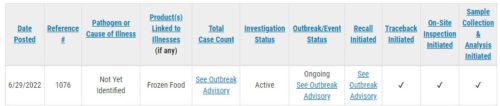

On July 1, the FDA announced the recall and issued an advisory for these events.

Also on July 1, Daily Harvest issued UPDATES ON OUR VOLUNTARY RECALL OF FRENCH LENTIL + LEEK CRUMBLES

Rachel here – I want to give you another update on the French Lentil + Leek Crumbles recall. As you know, we’ve been conducting exhaustive testing over the course of the last two weeks. Despite this, we still have not identified a possible cause. I am sorry that it’s taking as long as it is to pinpoint exactly what may have made people sick. We are deeply committed to finding answers for those impacted. We’re working with top doctors, microbiologists, toxicologists as well as 3 independent labs. While additional testing is underway, results to date rule out the following:

-

Hepatitis A

-

Norovirus

-

A range of mycotoxins, including aflatoxins

-

Food-borne pathogens including Listeria, E.Coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus Aureus (Staph), B.Cereus, and Clostridium Species

-

Major allergens including egg, soy, milk, and gluten

I assure you, we will not stop until we get to the bottom of this. We’re continuing to work in close cooperation with the FDA, CDC and other health agencies. The FDA released an update on their investigation yesterday, which can be found here on their website.

I’m baffled. I can’t understand why toxin testing hasn’t come up with anything. The illnesses are real and all traced to this product.

The FDA’s recommendation: “Consumers should not eat, sell, or serve recalled products. Consumers who may still have the recalled product in their freezers should throw it away.”

Bill Marler agrees with don’t eat it, but he wants the product saved as evidence. He has questions and suggestions:

His hypothesis: the Tara ingredient.

We believe that the illnesses may well be linked to a common ingredient called Tara that comes exclusively from Peru (this due because it is a unique ingredient to the French Lentil + Leek Crumbles AND to certain Revive Smoothies where people are reporting identical symptoms).

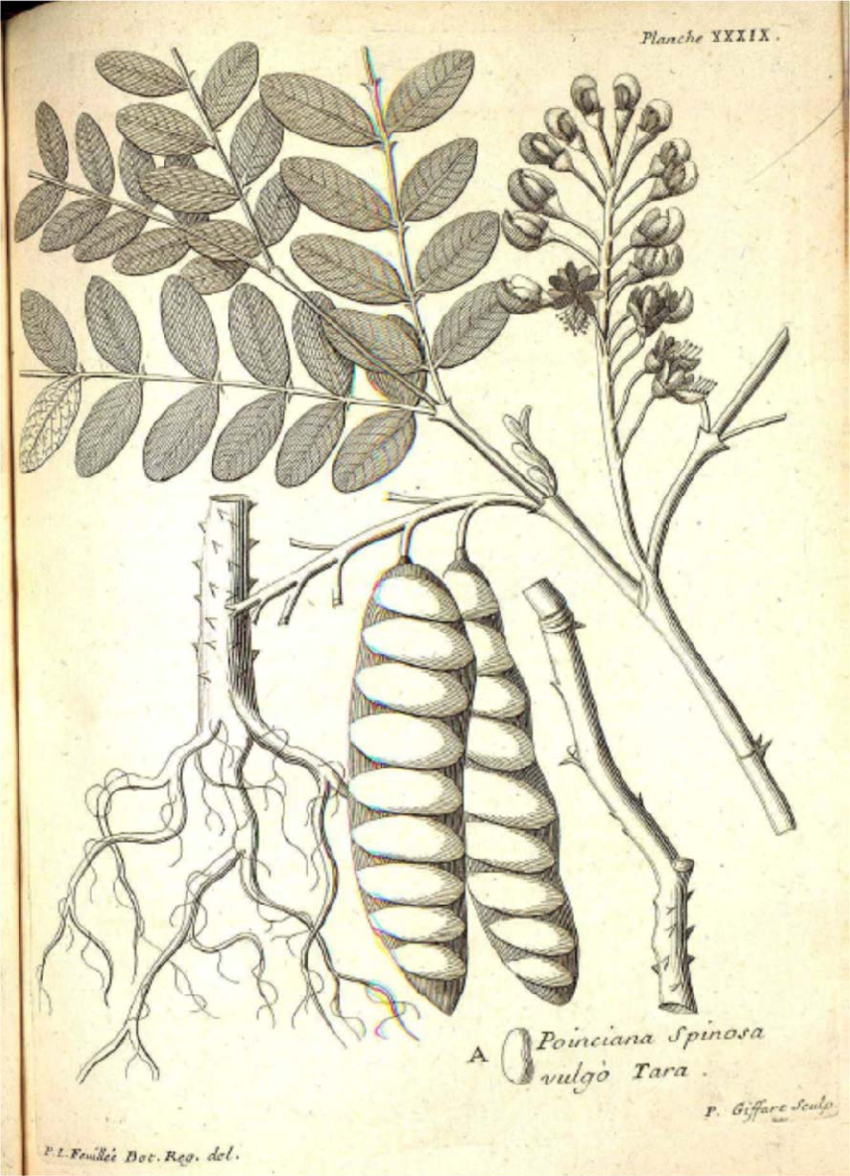

Here’s what Wikipedia says about Tara:

Tara gum…is produced by separating and grinding the endosperm of T. spinosa seeds…The major component of the gum is a galactomannan polymer similar to the main components of guar and locust bean gums that are used widely in the food industry….Tara gum has been deemed safe for human consumption as a food additive… Medicinal uses in Peru include gargling infusions of the pods for inflamed tonsils or washing wounds; it is also used for fevers, colds, and stomach aches. Water from boiled, dried pods is also used to kill fleas and other insects.

Bill Marler is on the case. He has 175 clients so far.

I’ve heard privately from people who experienced sickness after eating this product. I’ve read about others like this one:

I wish everyone a speedy recovery, and hope the toxin gets identified soon. Stay tuned.