Chipotle’s food safety issues: the saga continues

Food Safety News continues to be incredulous at Chipotle’s apparent denial of responsibility for the safety of food served in its outlets.

For sure, what has happened at Chipotle restaurants is unusual—illnesses caused by multiple toxic microbes at multiple locations:

- Seattle — E. coli O157:H7, July 2015, five sick people, source unknown;

- Simi Valley, Calif. — Norovirus, August 2015, 234 people, source was sick employee;

- Minnesota — Salmonella Newport, August and September 2015, 64 sick people, source was tomatoes but it remains unclear at what point in the field-to-fork chain the pathogen was introduced;

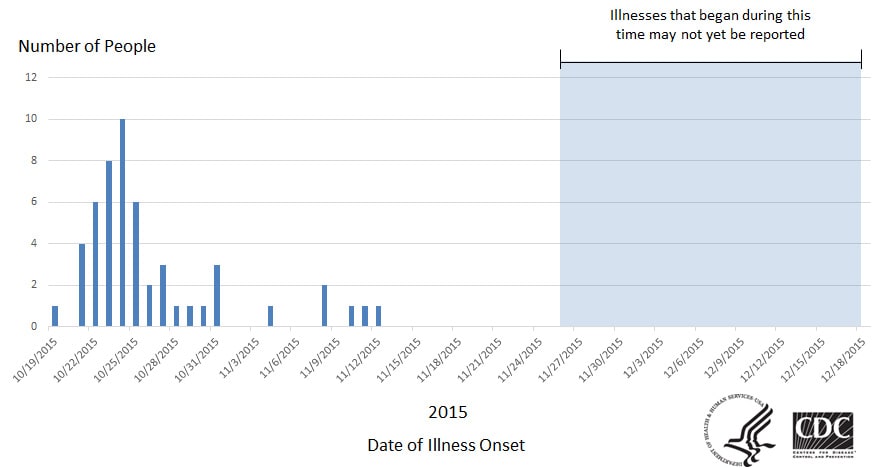

- Nine states — E. coli O26, began October 2015 and declared over Feb. 1, 55 sick people, source unknown, states involved are California, Delaware, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington; and

- Three states — E. coli O26, began December 2015 declared over Feb. 1, five sick people, source unknown, states involved are Kansas, Oklahoma and Nebraska; and closing out in

- Boston — Norovirus in December, 151 sickened.

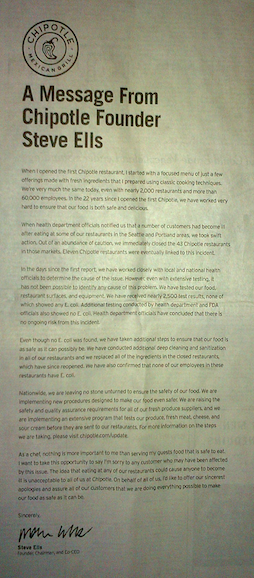

Chipotle did the obvious right thing. It brought on board the most experienced and highly regarded food safety experts: Mansour Samadpour (he has a food safety consulting company), James Marsden (to head up its food safety initiatives), Dave Theno (formerly of Jack in the Box) and David Acheson (former FDA food safety official).

Perhaps before they had time to weigh in, Chipotle’s counsel wrote a letter to the CDC complaining about the way the agency was conducting its investigation.

The CDC recently responded in no uncertain terms as Food Safety News discussed.

Food safety lawyer Bill Marler says:

My thought: “In 23 years being involved with every major food illness outbreak in the US, I have never seen a company take on the CDC or public health in this manner. Frankly, it is bizarre given that Chipotle was involved in multiple Salmonella, Norovirus and E. coli cases in 2015. As the CDC states in its responsive letter, it has to protect the public health and that is what it did.”

His view of the score: CDC 1, Chipotle Lawyer 0.

Chipotle’s food safety consultants have their work cut out for them. Let’s hope they figure out the problem and find ways to solve it—soon.