Here’s what I said about it.

Some years ago, I was in Woods Hole and hopped on the ferry to Martha’s Vineyard to visit Jessica Harris at her cottage in the historic African-American community at Oak Bluffs. I knew her as the distinguished culinary historian, cookbook author, and scholar of the African food diaspora. In the early years of NYU’s food studies program, she taught brilliant courses on food and culture that I sat in on whenever I could. She is now retired from a long teaching career at Queens College.

During that Oak Bluffs visit, Harris showed me boxes packed with old postcards depicting Africans – and their descendants throughout the world – growing, carrying, preparing, and eating food. I couldn’t stop looking at them, and I’ve never stopped wondering what happened to them. This book is the answer, and a perfect fit with the University of Mississippi’s series on Atlantic Migration and the African Diaspora, which Harris edits.

In addition to her other accomplishments, Harris is a passionate deltiologist, a term new to my vocabulary meaning one who collects – and sometimes studies – postcards, which Harris had been doing for fifty years. She begins the book with three short essays – a description of when, how, and where she amassed her collection; a discussion of what can be learned from postcards and the kinds of questions that need to be asked about them (illustrated with about 25 examples); and a history of the introduction and use of postcards from the 1870s on. She also includes guidelines on how to estimate a postcard’s date (not easy).

But most of the book is devoted to 168 color illustrations of postcards from her collection, almost all from the early 1900s. These illustrate people at work and play from Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States in three categories: farm, garden, and sea; marketplace, venders, cooks; and leisure, entertainments, and festivities. Their captions repeat information printed on the front, state whatever is printed or written on the back, and, if the card is stamped, give the date it was mailed. For example, a photograph of a Caribbean sugar warehouse (which reminded me of Kara Walker’s magnificent 2014 “sugar baby” sculpture in Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar Factory), is captioned: “Stacking Bags of Raw Sugar. Back: Post Card British Manufacture. Printed for the Imperial Institute by McCorquodale & Co. Ltd. London. A Red Bromide Photograph. (Divided Back.)” (84).

That’s it. Unless the card has this information, the captions say nothing about who took the picture, where, and in what year, who is depicted, its context, its purpose, or whether it was taken in a studio. In her introductory essay, “”Interrogating the Images,” Harris says “I am not a postcard scholar” (19). She collected and selected the cards for their illustration of culinary or cultural history and colonial exploitation, but also for their beauty, curiosity, or inscrutability. If you want to know more, it’s up to you to find that out and develop your own interpretation.

Despite that protestation, Harris cannot avoid taking a scholar’s approach. She points out the colonial attitudes expressed in the images or their titles–“elegant banana seller” (30), or the bare-breasted women selling foods at a “native” market in Dakar that looks like something out of the early years of National Geographic. This market could not possibly be in Dakar, Harris notes, Senegal is a Muslim country, where women did not appear in public unclothed.

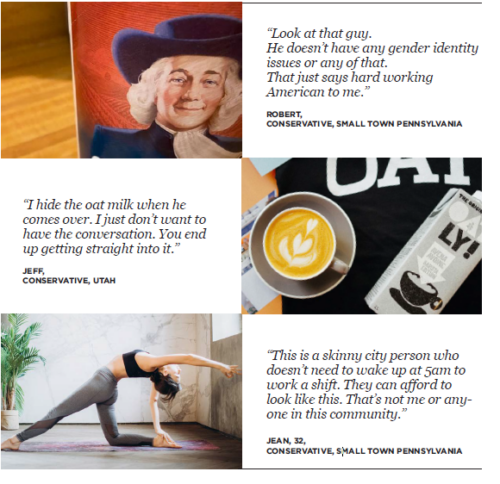

In this era of #BlackLivesMatter, it is uncomfortable to look at images of picturesque poverty or colonial exploitation: “Blacks in a Moorish café” (68), “Zulus at Mealtime” (69), or even “Water coconut vendor” (97) are depicted as exotics. Given its racist history, the United States postcards are particularly problematic: “Polly in the Peanut Patch” (110), “Negro Vegetable Vendor” (123), “Old/Southern Kitchen and Negro Manny” (130) should and do make us squirm. It’s hard to view “Food for contention” (135) as just a charming photograph of a little girl reaching for her brother’s watermelon slice if such images weren’t so fraught with racist meanings.

Each of these images has a story behind it that calls for analysis by food studies scholars. Harris’s Vintage Postcards should inspire all of us to become avid deltiologists.