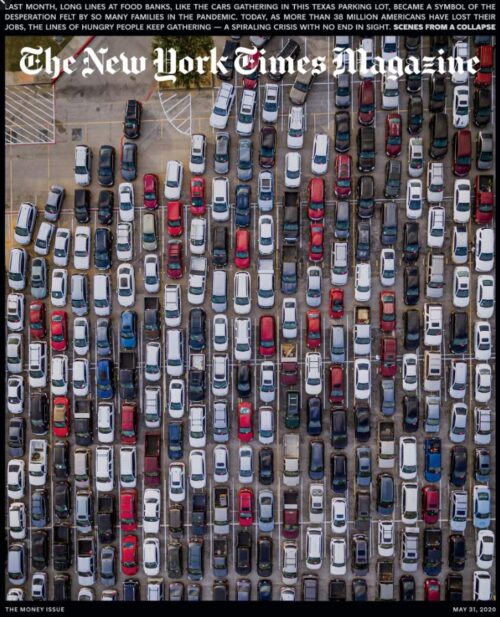

The continuing saga of the food boxes

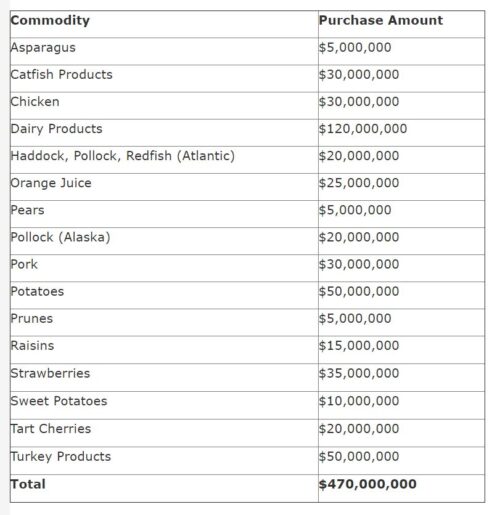

The USDA says 20 million food boxes have been delivered to food banks through the Farmers-to-Families program, which aimed to buy food from farms that had no way of selling what they produced, package it in boxes, and deliver them to food banks. The announcement comes with a very long list of testimonials, and a video that you can watch here.

The USDA’s website about this is here. The program is described here.

Not everyone is quite so enthusiastic. The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition says that the food box program is not exactly doing much for small farms.

Most of the news coverage on the CFAP Food Box Program, and the Congressional attention that follows, has focused on large contracts awarded to companies without much experience in the distribution of specialty crops. This also caused the larger specialty crop industry to raise concerns about the early shortcomings of the program.

What has received much less attention has been how the program has or has not benefited local and regional food producers despite the fact that the program was clearly intended to support these farmers. Grant applicants were required to discuss how their proposed project supports the mission of facilitating agricultural markets and how they “intend to engage small farmers (e.g those farms servicing local and region interests and farmers markets).”

And Chuck Abbott, of FERN’s Ag Insider, says USDA offers few yardsticks for measuring its food-box program.

For USDA, the most important number in its food-box giveaway program is how many boxes are donated — 18.4 million as of Friday, according to a tally on the homepage of the agency that runs the program. Officials declined to provide other details, such as the average cost of the boxes or how long the $3-billion initiative will be in operation.

I would like to know:

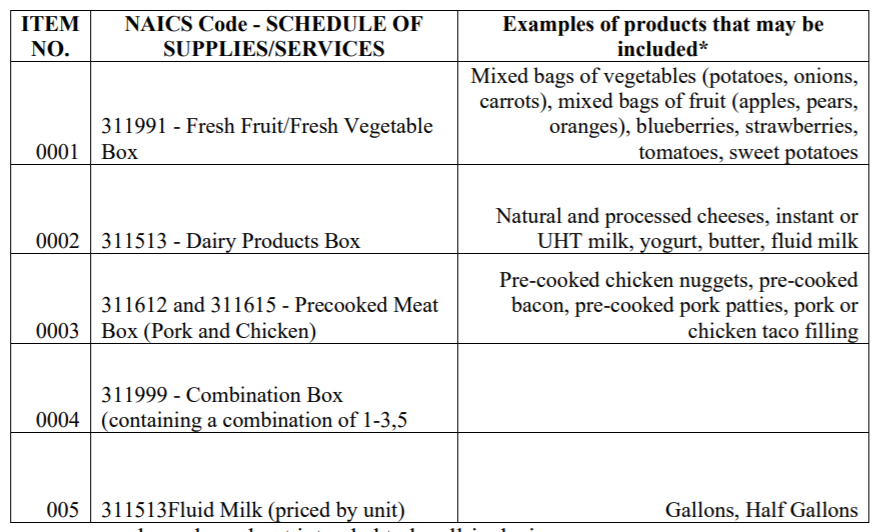

- What’s in the boxes?

- What food? How much food?

- What is its quality?

- How are food banks handling this?

- Are recipients happy with it?

- Is the program helping small farmers stay in business?

Does anyone know? I haven’t seen answers to these questions yet.