Advocacy groups sue FDA to get busy on safety standards

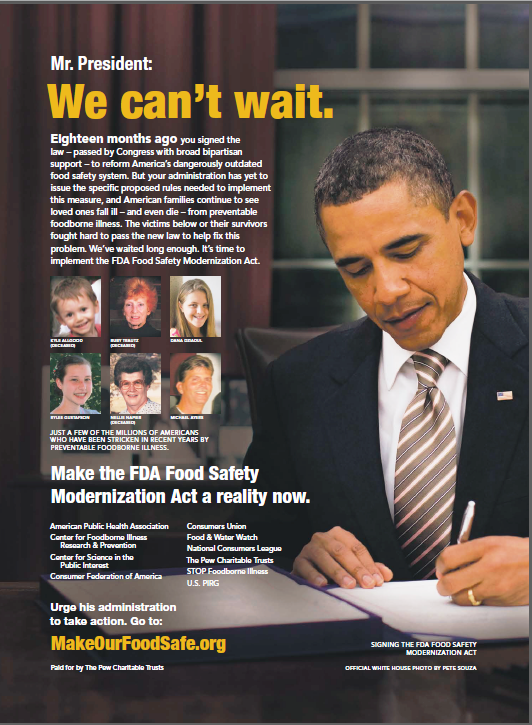

I’ve written previously about the holdup on implementation of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act by the White House Office of Management and Budget, reportedly because anything regulatory is likely to be a campaign issue in this especially contentious election year.

To get things moving, The Center for Food Safety and the Center for Environmental Health have sued the FDA to implement the rules on the grounds that the law requires federal agencies to conclude matters presented to them “within a reasonable amount of time.”

The suit complains that the FDA is failing to meet required deadlines for at least seven new food regulations and that nine more are coming due in 2013. It asks the court to order the agency to enforce the law right now.

In several instances, the FDA has attempted to make FSMA’s deadlines only to have its work held up at the White House Office of Management and Budget. FDA reported sending its proposed Foreign Supplier Verification Program to the OMB in November and its proposed produce safety standards in December, though the OMB has yet to release either regulation. Both were required by FSMA on Jan. 4.

FSMA also required FDA to establish standards for analyzing and documenting hazards and implementing preventative measures by July 4 of this year, the suit recounts.

The plaintiffs are especially alarmed that the FDA is not enforcing policies that are “self-executing,” meaning the new preventive standards for example.

From where I sit, the preventive standards are the critical factor in stopping outbreaks of foodborne illness before they happen.

While we are waiting for politics to resolve, the CDC keeps adding new outbreak home pages.

- Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Braenderup Infections Associated with Mangoes is the latest.

- Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Typhimurium Infections Linked to Cantaloupe isn’t over yet.

Would implementation of preventive standards help? Yes it would, especially if the problem is in the packing houses (packing houses can be cleaned).