Labor Day: an ever-timely food politics reminder

Enjoy the holiday!

The Food and Environment Reporting Network (FERN) announces that its long-time reporter, Leah Douglas, is leaving to take a job with Reuters.

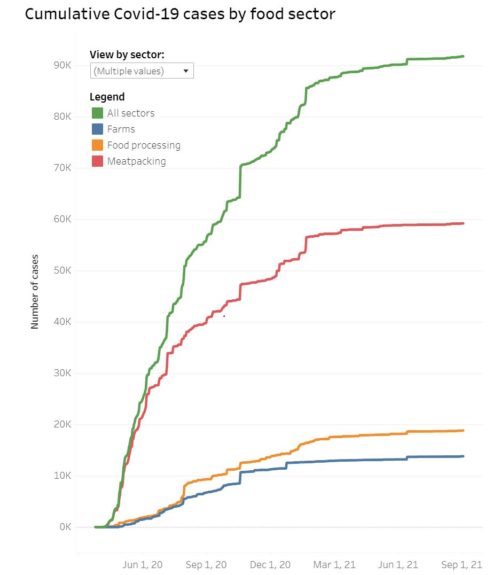

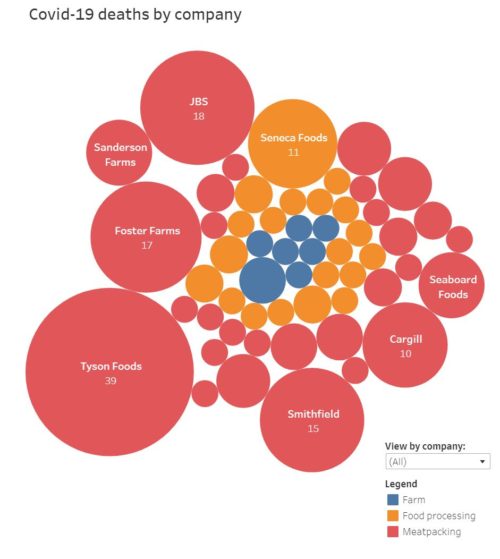

FERN is also giving up its counts of Covid cases and deaths among farm workers and meat-packing workers.

This week we wrapped up the mapping project of Covid-19 outbreaks at food-production facilities and farms around the nation. This nearly 18-month-long project, spearheaded and updated almost daily by staff writer and associate editor Leah Douglas, came to an end largely because of a lack of reliable data.

As Leah explains, companies and states have decided to keep much of their data secret, even with the rise of the Delta variant. But to date she has counted nearly 100,000 cases and 466 deaths among food system workers.

Here is an example of the data she produced. In the absence of any industry or government tracking, her project was all we had.

And here’s another one.

You can see why these companies don’t want anyone to have these data. Leah did a great job of working with what she could find.

I will miss her work on this project but look forward to seeing what she does for Reuters.

Congratulations Leah!

The summer is a good time to catch up on reports. Early in July, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO)—a government watchdog agency—sent a firm letter to USDA chiding that agency for not implementing GAO’s recommendations in a timely manner.

In November 2020, we reported that on a government-wide basis, 77 percent of our recommendations made 4 years ago were implemented…[but] USDA’s recommendation implementation rate was 46 percent. As of May 2021, USDA had 171 open recommendations. Fully implementing all open recommendations could significantly improve USDA’s operations.

Among the GAO’s recommendations were two of particular interest:

I. Strengthen Protections for Wage Earners. See: Workplace Safety and Health: Better Outreach, Collaboration and Information Needed to Help Protect Workers at Meat and Poultry Plants. GAO-18-12. Washington, D.C.: November 9, 2017.

Recommendation: The FSIS Administrator should work with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to assess the implementation of their agencies’ joint memorandum of understanding (MOU) regarding worker safety at meat and poultry plants and make any needed changes to ensure improved collaboration, and also set specific time frames for periodic evaluations of the MOU.

Comment: This is about the failure of OSHA and USDA to protect meat-processing and -packing workers from Covid-19 (for data on the effects of Covid-19 on these workers, see Leah Douglas’s regular reports on the Food and Environment Reporting Network. GAO is essentially calling on the two agencies to get busy on protecting workers at those plants.

II. Improve Cybersecurity. See Cybersecurity: Agencies Need to Fully Establish Risk Management Programs and Address Challenges. GAO-19-384. Washington, D.C.: July 25, 2019.

Recommendations: The USDA should (1) develop a cybersecurity risk management strategy that includes the key elements identified in this report; and (2) establish and document a process for coordination between cybersecurity risk management and enterprise risk management functions.

Comment: The GAO is asking USDA to work with other agencies to improve cybersecurity at meat-processing plants. Why? Because the meat industry’s weak cybersecurity—a long-standing problem—was recently exposed when hackers did a ransomware attack on JBS meat plants that cost the company $11 million to resolve.

Secretary Sonny Perdue has released his blueprint for the 2018 farm bill.

Its goal is to “improve services while reducing regulatory burdens on USDA customers” [translation: Big Ag].

USDA, he says, supports legislation that will do a great many things for farm production, conservation, trade, food and nutrition services, marketing, food safety, research and education, and natural resources.

There are a lot of words here and it’s hard to know what they mean, even reading between the lines.

For example, here are USDA’s principles for SNAP (food stamps), with my [translations and questions]:

• Harness America’s agricultural abundance to support nutrition assistance for those truly in need. [This sounds like a food distribution program, but I’m wondering how “truly in need” will be defined.]

• Support work as the pathway to self-sufficiency, well-being, and economic mobility for individuals and families receiving supplemental nutrition assistance. [This means work requirements, but where will the jobs come from?]

• Strengthen the integrity and efficiency of food and nutrition programs to better serve our participants and protect American taxpayers by reducing waste, fraud and abuse through shared data, innovation, and technology modernization. [This means spending hundreds of millions a year on fraud prevention].

• Encourage state and local innovations in training, case management, and program design that promote self-sufficiency and achieve long-term, stability in employment. [The jobs?]

• Assure the scientific integrity of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans process through greater transparency and reliance on the most robust body of scientific evidence. [Weren’t they always based on the available science? This sounds like a way to prevent the guidelines from suggesting eating less of junk foods].

• Support nutrition policies and programs that are science based and data driven with clear and measurable outcomes for policies and programs. [This one translates to you can’t set nutrition policies unless you can demonstrate beneficial outcomes—fine in theory, but policy-blocking in practice].

Reading through the other sections is equally non-reassuring. Where is a vision for a farm bill that promotes health, sustainable agriculture, and small or mid-size farms, protects farm workers, and reduces greenhouse gases?

Maybe the next one?

USDA’s charts make it easy to understand basic aspects of farming in the United States. This one covers about 175 years of American history. The number of farms fell fast after the end of World War II and is still declining, while the size of farms increased.

Where are the jobs in the food and agriculture industries? Mostly in food and beverage service and stores.

Farming? A mere 1.4%.

Sales of organic foods continue to increase at a faster pace than sales of conventional foods. This alone makes people suspicious of the organic enterprise.

Another reason is confusion about what organic production methods are, exactly. If you are part of the food movement, you probably want your foods to be organic, local, seasonal, and sustainable. You might also want them produced by farm workers who have decent wages and living conditions.

Unfortunately, these things do not necessarily go together.

That these are different is illustrated by a recent article in the New York Times about industrial organic production in Mexico. The story makes it clear that organics do not have to be local, seasonal, sustainable, or produced by well paid workers.

While the original organic ideal was to eat only local, seasonal produce, shoppers who buy their organics at supermarkets, from Whole Foods to Walmart, expect to find tomatoes in December and are very sensitive to price. Both factors stoke the demand for imports.

Few areas in the United States can farm organic produce in the winter without resorting to energy-guzzling hothouses. In addition, American labor costs are high. Day laborers who come to pick tomatoes in this part of Baja make about $10 a day, nearly twice the local minimum wage. Tomato pickers in Florida may earn $80 a day in high season.

The cost issues are critical. Dairy farms in general, and organic dairy farms in particular, are entirely dependent on the cost of feed for their animals, and the cost of organic feed has become almost prohibitively expensive. This has caused organic dairy producers to cut back on production or go out of business. As another New York Times article explains,

The main reason for the shortage is that the cost of organic grain and hay to feed cows has gone up sharply while the price that farmers receive for their milk has not.

While the shortage may be frustrating for consumers, it reveals a bitter truth for organic dairy farmers, who say they simply need to be paid more for their milk.

Why is the price of feed rising? Simple answer: because 40% of feed corn grown in the United States is being used to produce biofuels.

Why do farmers grow corn for biofuels? Because the government gives them tax credits and other subsidies to do so.

But in a small step in the right direction, the ethanol tax credit program was allowed to expire last week,”ending an era in which the federal government provided more than $20 billion in subsidies for use of the product.”

One person quoted in the article connected the dots:

Production of ethanol, with its use of pesticides and fertilizer and heavy industrial machinery, causes soil erosion and air and water pollution. And it means that less land is available for growing food, so food prices go up.

Organics do not exist in isolation. Their production is connected to every other aspect of the food system.

Wouldn’t it be nice to have a food system that promoted organic, local, seasonal, sustainable agriculture and paid farm workers a living wage?

Wouldn’t it be nice if the 2012 Farm Bill supported that kind of a food system if not instead of than at least along side of the one we have now?

I will be watching to see what Congress does with the Farm Bill. Stay tuned.