Why voluntary guidelines for marketing to kids can’t work

Some of the reaction to yesterday’s post commenting on guidelines for voluntary restrictions on marketing to kids focused on political realities. Given that our current Congress is highly unlikely to enact mandatory guidelines, improving voluntary guidelines is the best we can do.

Maybe, but some members of Congress are willing to take action.

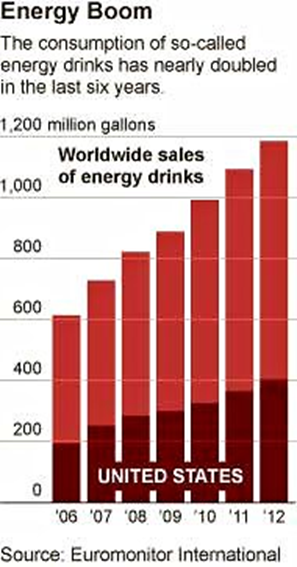

Take a look at Buzz Kill, a report on the marketing of highly caffeinated energy drinks by the staff of Senators Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) in coordination with the staff of Senators Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.), and Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.)

Concerned about the effects of these drinks on the health of America’s youth, the Senators held hearings and sent a questionnaire to the 16 major companies that make these drinks “to assess the extent to which the energy drink industry as a whole will commit to voluntary measures that will better protect young consumers and prevent misuse.”

Buzz Kill summarizes what they learned from the 12 companies that responded.

- Only 4 of the 12 companies said they would not market to youth under age 18 (these companies constitute 90% of the market).

- Only one company committed to all specific measures: labeling products as not intended for youth under age 18, restricting advertising buys to media where no more than 35 percent of the audience is under age 18, restricting social media access for youth under age 18, and avoiding featuring youth under age 18 in energy drink marketing campaigns.

- All but one of the responding companies said they would not market, sample, or sell their products in K-12 school settings, but 2 companies used equivocal language.

- 6 of 10 companies said they were willing to report adverse advents; 3 of 10 said they would do so under specified conditions, and 1 refused to report.

- 3 companies that belong to the American Beverage Association, which says its members are committed not to market caffeinated energy drinks as sports drinks, do so.

- Most of the 12 companies label caffeine content on their products, and say they will not promote rapid or excessive consumption or the mixing of energy drinks with drugs or alcohol.

- 4 of the 12 companies (representing 90% of the market) refuse to commit to protecting adolescents from targeted marketing campaigns.

Summary: the companies that own 90% of the energy drink market are largely unwilling to do much to stop marketing their products to kids under age 18.

Buzz Kill comes with recommendations. Here’s the first:

To protect youth, all energy drink manufacturers should cease marketing of energy drink products to children and teens under the age of 18 and sales of these products in K-12 school settings. Companies should engage with distributers and other third-party entities to ensure all contractual partners are bound by this commitment. Additionally, companies should put in place social media and online restrictions, and cease online appeals and marketing to children and teens.

It also comes with an ask: write a letter to the companies asking for stronger voluntary commitments.

It says nothing about regulation. But Buzz Kill provides plenty of evidence that nothing short of regulation will get these companies to stop such practices.

The Europeans are regulating energy drinks. We can too.