For years, some people – not me – have been saying that eating one extra 50-calorie cookie a day can make you put on 5 pounds per year. This calculation comes from basic math: if about 3500 extra calories make you put on a pound of body fat, then 50 times 365 is 18,250 extra calories which, divided by 3500, equals about 5 pounds.

This never made sense to me. It is impossible to know how much you are eating each day within 50 calories let alone how many calories you are using in daily activities. Yet people used to be able to keep their weight steady without thinking about calories at all.

This is because the body regulates weight and can easily compensate for such small changes in calorie intake or output with small changes in metabolic rate. It takes more calories to move heavier bodies, and fewer to move lighter ones.

For years, I’ve been thinking that it must take a lot more than 50 extra calories a day – I guessed hundreds – to make people gain weight. I thought this for two reasons:

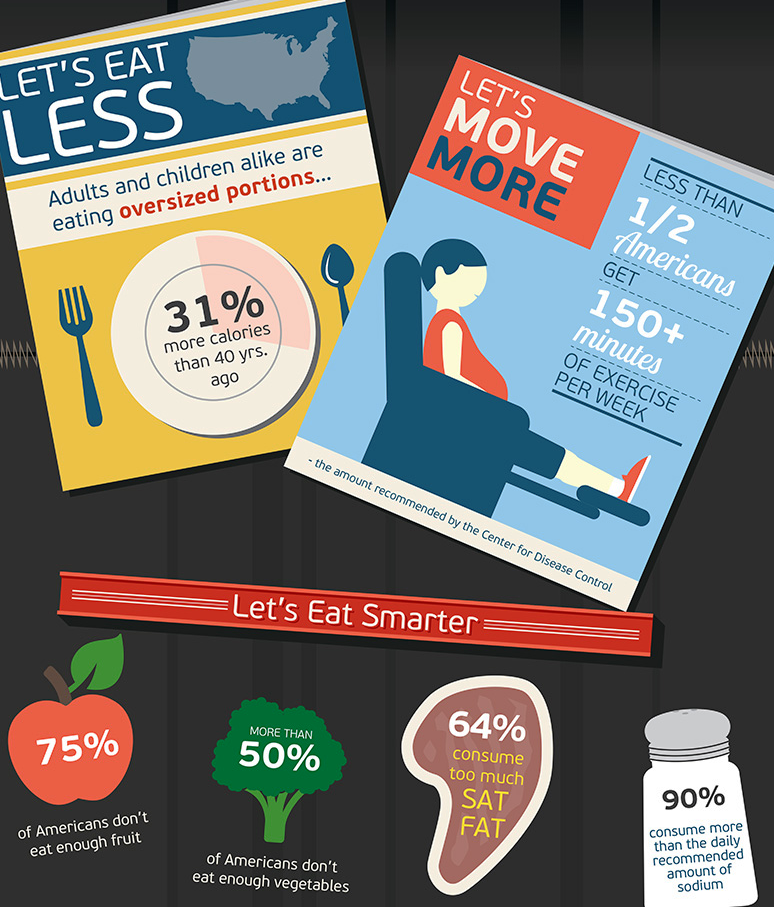

First reason: Portion sizes have increased greatly in recent years, and larger portions have more calories. Sometimes, they have a lot more. Foods eaten outside the home often have more calories in them than anyone suspects.

That’s why calorie labeling matters. Labeling may underestimate the actual calories present in a food according to Tufts researchers (see this week’s Time for commentary and also see the industry response). But even so, a new study shows that labeling encourages people to cut down on food intake, at least at Starbucks. Make that two new studies: one from the Rudd Center at Yale comes to the same conclusion.

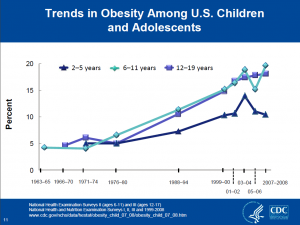

Second reason: I keep hearing from pediatricians who treat overweight kids that they have kids in their practices who drink from 1,000 to 2,000 calories a day from sodas alone. I can’t judge whether these figures are correct or not, but several different kinds of studies suggest that many people today are eating a lot more calories than their counterparts of 25 years ago.

Now Martin Katan and David Ludwig have done the actual calculations in a paper in this week’s JAMA titled “Extra calories cause weight gain–but how much?” Their conservative estimate is that it would take an excess of 370 calories to gain 35 pounds in 28 years. To become obese in 25 years, you would need to eat 680 calories a day more than you expended.

To become 58 pounds overweight at age 17, they predict that a child would need to overconsume 700 to 1,000 calories a day from the age of 5 or so.

These figures are quite consistent with what those pediatricians were telling me. By other estimates, average caloric intake has increased by 200-500 calories a day since the early 1980s, along with a 700 calorie-a-day rise in the availability of energy in the food supply (from 3,200 to 3,900 per day per capita).

As Katan and Ludwig conclude:

small changes in lifestyle would have a minor effect on obesity prevention. Walking an extra mile a day expends, roughly an additional 60 kcal compared with resting – equal to the energy in a small cookie. Physiological considerations suggest that the apparent energy imbalance for much of the US population is 5- to 10-fold greater, far beyond the ability of most individuals to address on a personal level. Rather, an effective public health approach to obesity prevention will require fundamental changes in the food supply and the social infrastructure.

This is because on the personal level, prevention of weight gain means eating hundreds of calories a day less. Moving more, useful as it is, will not do the trick unless people eat less as well.

On the societal level, we need measures to make it easier for people to eat less.

I can think of a bunch of examples. You?