More on the 2020 Dietary Guidelines

I only have a few more comments about the Dietary Guidelines beyond what I posted last week.

One is my surprise that the USDA did not do a new food guide. The existing one, after all, dates from the Obama administration. It has not changed.

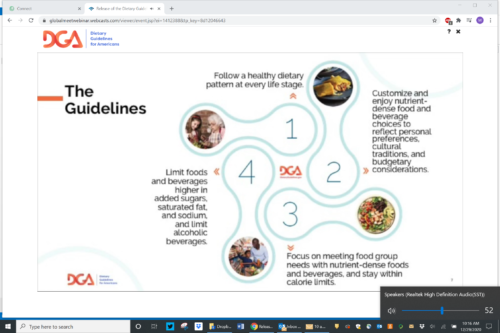

Here’s how it is explained in the new guidelines:

My translation: Eat more plant foods, eat less meat, avoid ultraprocessed foods (including sugary beverages).

This requires a translation because the guidelines say nothing about ultraprocessed junk foods, and they try hard to avoid singling out foods to avoid.

These guidelines are similar to those in 2015 and are, therefore, woefully out of date.

They do mention the pandemic, once:

The importance of following the Dietary Guidelines across all life stages has been brought into focus even more with the emergence of COVID-19, as people living with diet-related chronic conditions and diseases are at an increased risk of severe illness from the novel coronavirus (p. 4).

They do mention food insecurity several times, for example:

In 2019, 10.5 percent of households were food insecure at least some time during the year. Food insecurity occurs when access to nutritionally adequate and safe food is limited or uncertain. Food insecurity can be temporary or persist over time, preventing individuals and families from following a healthy dietary pattern that aligns with the Dietary Guidelines. The prevalence of food insecurity typically rises during times of economic downturn as households experience greater hardship. Government and nongovernment nutrition assistance programs help alleviate food insecurity and play an essential role by providing food, meals, and educational resources so that participants can make healthy food choices within their budget (p. 50).

And they do mention food assistance programs (on page 81), although they do not discuss how the USDA has been relentless in trying to cut those programs.

Nothing about food systems. Nothing about the effects of food production and consumption on climate change and sustainablity.

Nothing about eating less meat other than implying that eating less processed meat might be a good idea.

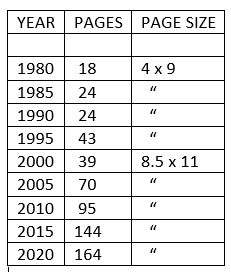

One other point: the complexity is increasing. Here is the history of the page numbers:

As I’m fond of saying, Michael Pollan can do all this in seven words: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

If we can’t do better than this 164 pages of obfuscation, isn’t it about time to stop requiring these things every five years?

Here’s what other people are saying about them

- New York Times report (I’m quoted)

- Wall Street Journal (quotes American Beverage and Beer Associations)

- New York Daily News (I’m quoted)

- CNN (I’m quoted)

- Bipartisan Policy Center [Dan Glickman (Dem) and Ann Veneman (Rep), former USDA secretaries]

- Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (accuses guidelines of racial bias)

- USA Today

- National Fisheries Institute

- Produce for Better Health Foundation