I thought it might be time for a summary of why USDA’s new requirements for poultry inspection are so controversial. Some groups think they are a big step forward; others most definitely do not.

The USDA says its new rules, which are largely based on research published in 2011:

- Will place new requirements on the poultry industry.

- Will prevent 5000 illnesses a year from Salmonella and Campylobacter

- Puts trained USDA inspectors where they will do the most good.

- Require poultry facilities to test for Salmonella and Campylobacter at two points during production (USDA will continue to do its own testing).

- Giving poultry producers the option of doing their own inspections.

- Caps the maximum line speed at 140 birds per minute (rather than the 175 the industry wanted).

- Estimates the public health benefit at $79 million.

It also says

More inspectors will now be available to more frequently remove birds from the evisceration line for close food safety examinations, take samples for testing, check plant sanitation, verify compliance with food safety plans, observe live birds for signs of disease or mistreatment, and ensuring plants are meeting all applicable regulations.

To read the Federal Register notice (when it’s ready), click here.

The main issues

Line speed: this refers to the evisceration line and is the speed at which workers must deal with the chickens. The current speed is 140 birds per minute. This means 2.33 birds per second. It’s hard to imagine that any worker could manage that—or any inspector could see anything—at that speed.

The National Council of La Raza wrote USDA in 2012 that raising the line speed posed a hazard to worker safety and “would recklessly threaten the health and safety of poultry workers.” USDA listened. The NCLR must be pleased.

The poultry industry is not pleased. The National Chicken Council complains that “politics have trumped sound science, 15 years of food and worker safety data and a successful pilot program with plants operating at 175 birds per minute.”

Politico ProAg points out that the new system will cost the poultry industry $259 million—what it would have gained if line speeds increased to 175 per minute.

Privatization of inspectors. The new rules shift responsibility for inspecting chickens, no matter how impossible, to company employees—the fox guarding the chickens, as it were. Food and Water Watch argues that this poses a conflict of interest since it’s in the managers’ interest to keep the lines moving as fast as possible and not to find anything wrong. Food and Water Watch says the new system “will transfer most poultry inspection from government inspectors to the companies so they can police themselves.” Several members of Congress have also complained. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report noting that USDA doesn’t really have data on which to base this change.

Change in function of USDA inspectors. Up to 1,500 USDA phased out of poultry production may have to relocate or retire. USDA estimates it will save $90 million over the next three years from this reduction.

Turkeys. The new system allows turkey plants to raise line speeds to 55 per minute, up from 51 birds per minute. The National Turkey Federation says most turkey plants will comply.

Waivers. The Washington Post says the new system “provides a waiver to 20 plants that are already in a pilot program, letting them operate at 175 birds per minute.”

Voluntary. The program is voluntary. Plants can continue doing things the way they are.

What to make of all this? The testing requirements are a huge step forward. The inspection changes seem mixed. It’s hard to believe that line inspection is useful even at 140 birds per minute.

I’d rather have USDA inspectors making sure prevention controls are in place and adhered to, the testing is done honestly, and keeping an eye out for unsafe worker conditions (which, alas, is not their job).

Let’s give it a try and see how it works in practice.

In the meantime, here’s what else is happening on the poultry safety front:

Other related news

Salmonella is not an adulterant, says USDA. If it were, anything contaminated with it could not be sold. USDA denied the petition from Center for Science in the Public Interest to have four antibiotic-resistant strains of salmonella declared as as adulterants in ground meat and poultry products.

After thoroughly reviewing the available data, FSIS has concluded that the data does not support giving the four strains of [antibiotic-resistant] salmonella identified in the petition a different status as an adulterant in raw ground meat and raw ground poultry than salmonella strains susceptible to antibiotics.

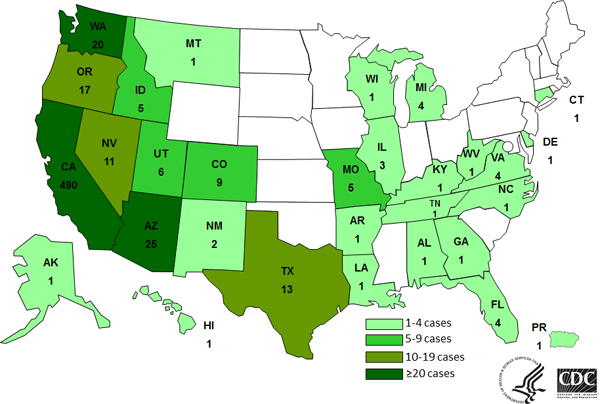

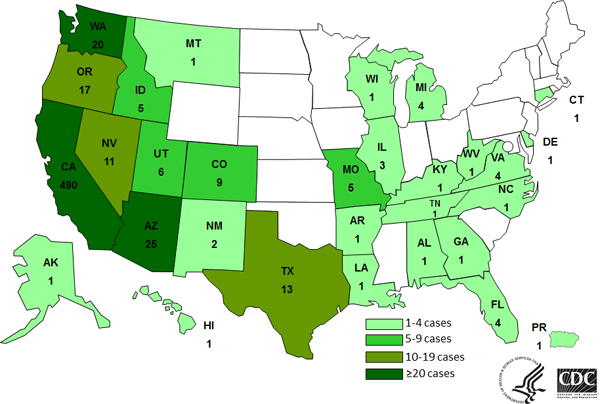

The Foster Farms Salmonella outbreak is over, says the CDC.

The CDC announced today a total of 634 persons infected with seven outbreak strains of Salmonella Heidelberg were reported from 29 states and Puerto Rico from March 1, 2013 to July 11, 2014.

Epidemiologic, laboratory, and traceback investigations conducted by local, state, and federal officials indicated that consumption of Foster Farms brand chicken was the source of this outbreak of Salmonella Heidelberg infections.

38% of ill persons were hospitalized, but no deaths were reported.

Most ill persons (77%) were reported from California, but cases were reported in other states as well.

And that’s why all of this matters so much.