My 2012 book with Mal Nesheim, Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics, includes a chapter on the use of calories in international relations.

I thought of this chapter while reading a story in yesterday’s New York Times.

Apparently, the Israeli military restricted the amount of food available to residents of Gaza during the blockade that lasted from from 2007 to mid-2010.

The Israeli military calculated the number of calories that the blockaded residents would need to avoid malnutrition.

The purpose of the blockade was to weaken support for Hamas, the militant group that won legislative elections in 2006 and took full control of Gaza in 2007 after a brief factional war…In the calculation, Israel applied an average daily requirement of 2,279 calories per person, in line with World Health Organization guidelines.

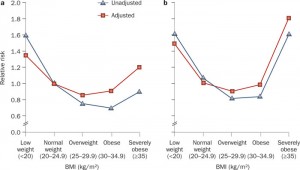

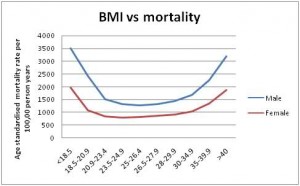

I’m not sure where the 2,279 figure comes from. Calorie estimations established jointly by the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization say that adult men aged 20-70 need 2400 to 3000 calories a day on average, depending on age, weight, and physical activity level. Adult women need 1800 to 2400.

The FAO sets a calorie cut point for populations to define hunger. It defines populations consuming 1,800 calories per capita per day, on average, as chronically undernourished and hungry.

On this basis, 2,279 will be adequate for some adults—those who are female, smaller, older, and less active. It is unlikely to be adequate for younger, bigger, more active men.

The Israeli Defense Ministry released this document under a court order. It would be interesting to see how it arrived at this figure.

For an interesting discussion of the use of calories as an instrument of state power, see Nick Cullather’s “The Hungry World: America’s Cold War Battle against Poverty in Asia.”