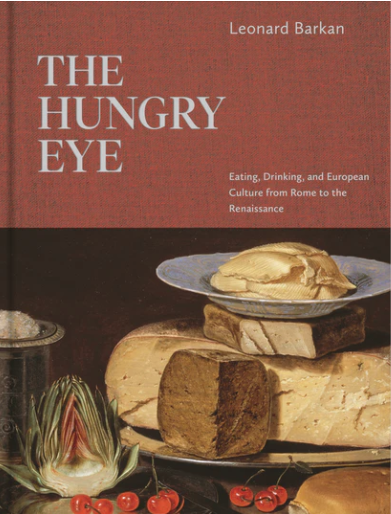

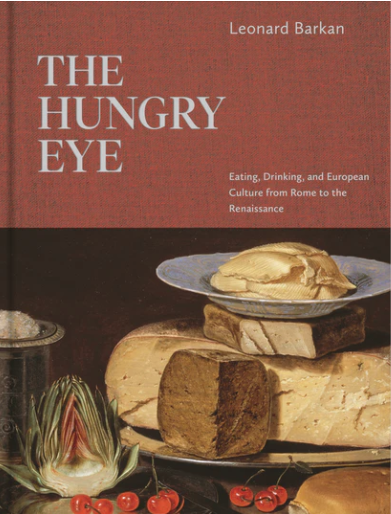

Leonard Barkan. The Hungry Eye: Eating, Drinking, and European Culture from Rome to the Renaissance. Princeton University Press, 2021.

What a treasure.

I still get asked all the time: “What is Food Studies?”

Leonard Barkan, Professor of English and Art, and my esteemed NYU colleague until he was seduced away by Princeton, directly answers that question in this book.

…food and drink can scarcely enter cultural discourse without forming either the center or the outer periphery of an argument.” (p. 142)

Food, he insists, inserts itself into everything human. The tension between its material (earthy) and metaphorical (symbolical) meanings makes food impossible to ignore.

Barkan reads for the food. In doing so, he invents a new term,”fooding” (analagous to “queering” as an analytic technique), to explore and interpret art and literature.

This book does for food in art and literature what Sidney Mintz did for food and global politics in Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. It should be right up there with Mintz’s book as a foundational text of Food Studies.

Hungry Eye illustrates the concepts with hundreds (literally) of images of mosaics, drawings, and paintings—in full color.

One, to which Barkan often refers, is of a mosaic now in the Vatican, “Unswept Floor,” which depicts the detritus of a sumptuous dinner party. It’s material meaning? Garbage. “…the Unswept Floor is a monument to the possibilities of rendering edibles as art” (p. 33). Its metaphorical meanings? Take your pick: wealth; power; disgust; eat or be eaten; here today, gone tomorrow. [And see Digression below at **]

The book’s them is illustrated with an etching from this painting of a bucolic scene titled “Pensent-ils au raisin?”

Barkan explains,

The cigar in this case is not just a cigar; it fact, it’s scarcely a cigar at all. With this image in front of us and the question, “Are they thinking about the grapes?” having been posed, we know the answer: Hell, no! Who would think of food at a time like this?

Clearly, I would. (p. 14)

Because he is reading for the food.

In this example, you might not pay attention to the old woman with a basket of eggs to the right of all the action in this painting by Titian.

But Barkan does.

But sometimes—and this will continue to be a recurrent theme of this book—food places a demand on the viewer that it be read as the thing itself. What is utterly distinctive about Titian’s egg seller is her extraordinary frontal position in the painting…For me, this is not so ambiguous, nor it is merely an implication…What Titian was offering on behalf of his employers was, along with the representation of a sacred scene, some very familiar nourishment. (p. 93-94)

He reads for food in the Bible,

I would argue that the Bible, and the traditions of representation that follow from it, display an interest in eating and drinking that is more constant than might have been noticed, and furthermore that there are ways in which those instances, taken together, can be seen as systematic rather than merely accidental or marginal. (p. 95)

Eating and drinking, along with the practices that make them possible, are not exclusively metaphors, of course. The New Testament never lets us forget that hunger and thirst are real. Miracles like the filling of the disciples’ nets with fish or the feeding of the five thousand or the four thousand out of a diminutive supply of loaves and fishes, not to mention the rather less solemn instance of producing wine in water jugs when the booze has run out during the wedding at Cana, are significant because the functions of gaining nourishment and experiencing commensality are eminently worthy of the divide efforts undertaken by the Son of God. (p. 99)

You are interested in botanical science or the Columbian Exchange? See what he says about depictions of fruit and vegetables in early 16th Century Italian wall paintings.

The range of species is astonishing: five types of grains, five types of legumes, eight forms of nuts, seven forms of drupes, nineteen forms of berries, six varieties of apple, and four types of aggregate fruits…What is even more remarkable is that we are able to identify each of these species…Up to date, it turns out, in the most radical way, as is clear from the presence of several species from the New World, including multiple types of squash or gourds…and, most astonishing to inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere, zea mays…or corn on the cob. As these representations appeared just over two decades from the date of Columbus’s first voyage, it seems that gastronomic news has traveled quite fast. (p. 192)

The book shows many different representations of The Last Supper. What were the artists trying to tell us about the relationship of the food on the table to Christian symbolism?

What kind of relation, then, might we postulate, in regard to food and wine, between the literal and the metaphorical? There are, after all, seven sacraments, at least in the Catholic church. None of them has undergone the wars of interpretation that the Eucharist has: that, I believes, is because it involves eating and drinking, because it consists of literal ingestion. Once again, it’s the sign at the entrance to the gullet that reads, “The metaphor stops here.” (p. 241.)

As for the literal and metaphorical meanings of the Eucharist itself?

Let us bring this discourse radically down to earth, from theology to experience and from medieval debate to twenty-first-century cyberspace, One has only to google the question “Should I chew the host? To discover that hundreds, possibly thousands of Christians—mostly Catholics, it seems—have spent their time at the altar rail in a desperate state of uncertainty, not about the transcendental meaning of the sacrament or the precise reality of the real presence but about what they should be doing with their teeth and tongue. The answer to this question (spoiler alert) is that is to raise the question whether I am eating Jesus or eating dinner. And the church is silent on this point. (p. 246).

I could go on and on but everyone interested in Food Studies as a discipline, food in art, and anything having to do with food and culture will want to read this book—for its ideas, its gorgeousness, and for sheer pleasure.

I will never again ignore depictions of food in paintings or look at them in the same way.

Thanks Leonard.

**And here’s the digression: When I saw the photos of Unswept Floor, I thought immediately of the bronzed garbage embedded in the road at the site of Boston’s old Haymarket, which I just loved and went to admire every time I went to Boston. But the last time I looked for the pieces, they were gone. I just looked it up—they will be resinstalled at some point—but the best part is that the entire installation was inspired by Unswept Floor, as described here.

Peter Hoffman, the chef-owned of the much loved and late-lamented Savoy restaurant in Manhattan’s SoHo has written an account of its rise and fall along with a close examination of what went into it, foods, ingredients, and emotions.

Peter Hoffman, the chef-owned of the much loved and late-lamented Savoy restaurant in Manhattan’s SoHo has written an account of its rise and fall along with a close examination of what went into it, foods, ingredients, and emotions.