President Trump’s $2 Trillion relief package is the “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020.’’

This 880-page (!) bill addresses food systems in several ways, most of them in “Title I Agricultural Programs” which starts on page 609 like this:.

For an additional amount for the ‘‘Office of the Secretary’’, $9,500,000,000, to remain available until expended, to prevent, prepare for, and respond to coronavirus by providing support for agricultural producers impacted by coronavirus, including producers of specialty crops, producers that supply local food systems, including farmers markets, restaurants, and schools, and livestock producers, including dairy producers: Provided, That such amount is designated by the Congress as being for an emergency requirement pursuant to section 22 251(b)(2)(A)(i) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency 23 Deficit Control Act of 1985.

This sounds good (in Ag-speak, specialty crops are fruits and vegetables), but what this means in practice, according to the New York Times, is

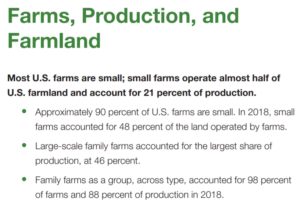

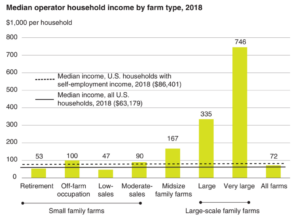

- About $23.5 billion in assistance to farmers ($9.5 in subsidies, $14 in borrowing authority)

But this will go mainly to soy and corn producers, key Trump constituents in an election year. This amount follows nearly $26 billion in aid already provided to offset losses from the China trade war. This new funds exceed USDA’s entire discretionary budget request for next year. The USDA Secretary may allocate the funds as he wishes, with no oversight.

So much for welfare for the rich.

As for the poor, the bill provides

- About $25 billion for food assistance (domestic food programs $8.8 billion, SNAP $15.8 billion).

This too sounds like a lot but all it does is account for the expected increase in demand from people newly out of work. It does not in any way increase the amount that individuals and families receive.

How did this happen? Chalk it up to effective lobbying by agribusiness.

The gains for agribusiness were accomplished, says the Times, by “A small army of groups mounted the fast-moving campaign for aid, including the politically powerful American Farm Bureau Federation and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. Joining them were other smaller players representing producers of goods like turkey, pork and potatoes or sunflowers, sorghum, peanuts and eggs.”

Earlier, Politico reported that nearly 50 organizations representing farmers, equipment manufacturers and agricultural lenders sent a letter stating their needs as a result of declining demand from school and restaurant shutdowns and direct-to-consumer sales.

The bill does little to help the folks who most need help. Anti-hunger groups tried, but failed.

Poor people need to vote. And organize.