Food trends predicted for 2021

I’ve been collecting predictions of what’s going to happen to the food industry this year. Here are some, about cooking, sales, products, flavors, regulations, e-sales, robotics, and agriculture.

- Waitrose identifies top 2021 consumer food trends: Home cooking, support for British producers and winter barbecues are just some of the key trends highlighted in Waitrose’s 2021 food and drink report. Read more

- Food industry trends for 2021: Key industry figures predict where the challenges and opportunities will be found in 2021. Read more

- 2021 Food Trends Product Developers Must Know: Find out which trends R&D chefs and CPG food manufacturers should focus on to drive profits.

- What trends will shape flavour innovation in 2021? The seismic events of 2020 have shaped consumer behaviours and expectations. The COVID-19 pandemic has reached every part of our lives – and the flavours we crave are no exception. Here’s our round-up of the flavour trends we can expect to tickle out taste buds in 2021… Read

- From ‘dark kitchens’ to dual quality: Expert predicts 2021’s regulatory hotspots: What regulatory challenges should food makers be mindful of in 2021? Read

- Retail predictions 2021: Experts talk bricks-and-mortar and the ‘jet propulsion’ of e-commerce: What key challenges are in store for supermarket retailers as we move into 2021? Will bricks-and-mortar continue to play an important role? Do experts predict e-commerce to continue its unprecedented boom?.. Read

- Robotics, AI and the future of food: ‘The COVID-19 pandemic is a crisis that robots were built to address’: COVID-19 has accelerated interest in the role that automation, robotics and data can play in food and agricultural production. We speak to industry leaders to learn about the latest developments… Read

- Eat the rainbow: ADM expects consumers to explore beyond their palate’s comfort zones in 2021: Colour plays a vital role in delighting the senses, differentiating flavour expectations and aiding in taste perceptions. It also adds to consumer’s assessment of the snack’s ‘health halo’… Read

- FrieslandCampina Ingredients sees four key trends for 2021: FrieslandCampina Ingredients has released a new report outlining the trends and developments for the future of performance and active nutrition… Read

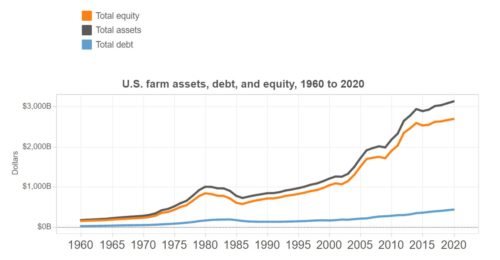

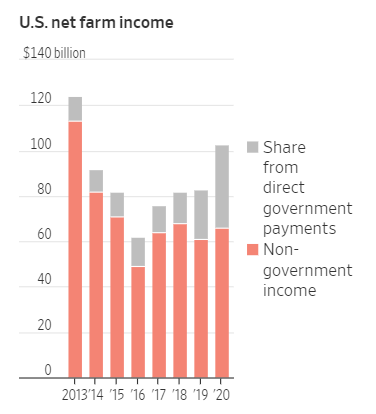

- 9 Questions Facing Agriculture In 2021: Each year Agricultural Economic Insights carves out time to think about the issues and uncertainties facing agriculture in the coming year.

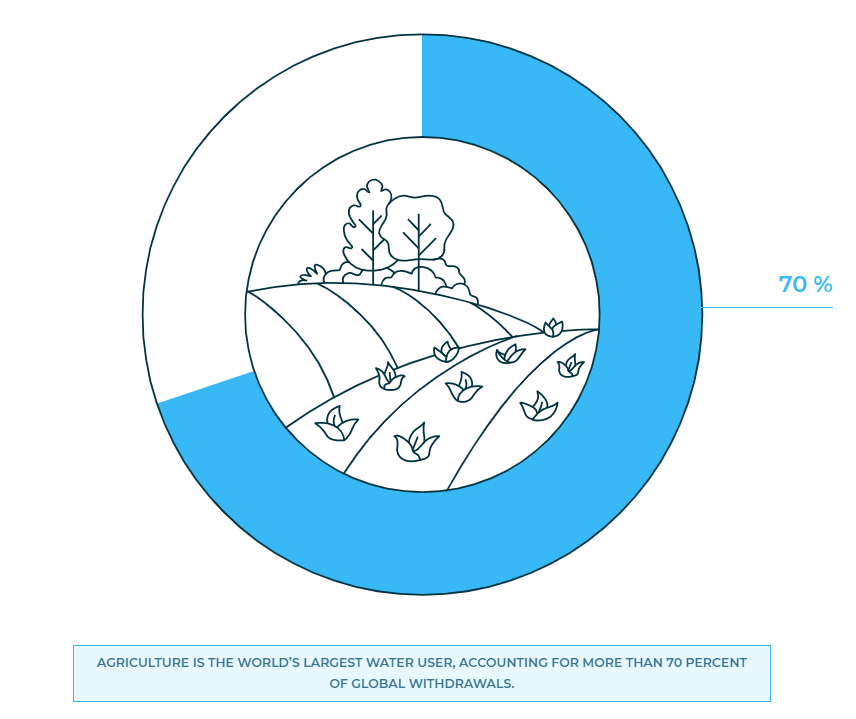

Everyone needs to pay attention to water use, and the teaser and the report state the policy recommendations.

Everyone needs to pay attention to water use, and the teaser and the report state the policy recommendations.