I’ve been collecting items about China’s food system as well as that country’s role in ours.

Podcast: The scientist whose hybrid rice helped feed billions: A historian reflects on the life of Chinese crop scientist Yuan Longping, and the possible influence of geothermal energy production on earthquake aftershocks.

BMI and obesity trends in China: Limin Wang and colleagues use data from six representative surveys in China…The authors report that standardised mean BMI increased from 22·7 kg/m2 (95% CI 22·5–22·9) in 2004 to 24·4 kg/m2 (24·3–24·6) in 2018, and obesity prevalence from 3·1% (2·5–3·7) in 2014 to 8·1% (7·6–8·7)…in 2018, an estimated 85 million adults (95% CI 70 million–100 million; 48 million men [95% CI 39 million–57 million] and 37 million women [31 million–43 million]) aged 18–69 years in China were obese.

China says it will buy US farm products: Bloomberg News reported on Friday that, “China plans to accelerate purchases of American farm goods to comply with the phase one trade deal with the U.S. following talks in Hawaii this week.

Chinese holdings of US agricultural land: According to USDA’s data on foreign ownership of US land, China owns about 192,000 agricultural acres, worth $1.9 billion. This includes land used for farming, ranching and forestry,.

The House introduces legislation to prevent China from buying U.S. farmland: Texas representative Chip Roy has introduced the “Securing America’s Land from Foreign Interference Act” to “ensure that Texas’s land never comes under the control of the CCP [Chinese Communist Party] by prohibiting the purchase of U.S. public or private real estate by any members of the CCP. [Comment: I’m guessing this won’t get very far, in part because China is an important trading partner].

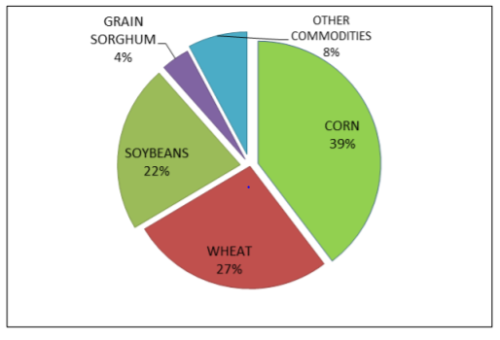

Balance of trade with China: U.S. exports of agricultural products to China totaled $14 billion in 2019, largely from soybeans ($8.0 billion); pork and pork products ($1.3 billion); cotton ($706 million); tree nuts ($606 million); and hides and skins ($412 million). U.S. imports of agricultural products from China totaled $3.6 billion in 2019, mainly from processed fruit and vegetables ($787 million); snack foods ($172 million); spices ($170 million); fresh vegetables ($136 million); and tea, including herbal tea ($131 million). [Comment: we were way ahead on the balance in 2019].

China Focus: Yeyo’s Tmall launch, Chinese dietary spending trends, local cultivated meat developments and more feature in our round-up: China’s first coconut yoghurt brand Yeyo’s Tmall launch, Chinese dietary spending trends, local cultivated meat developments and more feature in this edition of China Focus…. Read more

‘Follow, not lead’: China likely to be world’s largest cultivated meat consumer – but long, challenging journey ahead: China looks likely to be the world’s largest consumer market of cultivated meat due its population size and government support, but a long, arduous journey lies ahead before this becomes a reality, according to an industry expert…. Read more

Deliciou-s bite: Shark Tank alumni sets sights on China with first shelf-stable plant-based meats after cross-country supermarket success: Australia-based Deliciou has its eye on China and other Asian markets with its market-first shelf-stable plant-based meat products after successful launches in both Australia’s Coles and Woolworths and US’ Whole Foods supermarkets…. Read more

Comment: I visited Beijing in 2019 and was surprised by the emphasis on dairy foods (never part of traditional Asian diets) and snack foods, especially for children. Weight gain is only to be expected. Current political tensions must be understood in the context of trade relations. Although we export more agricultural goods to China than we import, our overall trade balance is to import about $300 billion a year more in products made in China than we export.