Good news about farming!

How about some good news for a change?

I. Politico reports on on a new report, Feeding the Economy, on the importance of agriculture for the US economy (you can search the site for your own state and congressional district).

The findings are impressive:

As Politico puts it, “more than a fifth of the U.S. economy and a quarter of American jobs are either directly or indirectly tied to the food and agriculture sectors.”

That’s more than 43 million jobs and $1.9 trillion in wages, and $894 billion in taxes. That’s $6.7 trillion for the impact..

Who paid for the study? 22 food and agriculture groups, including the Corn Refiners Association, the American Bakers Association and the United Fresh Produce Association.

II. The Washington Post writes:

For only the second time in the last century, the number of farmers under 35 years old is increasing, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s latest Census of Agriculture. Sixty-nine percent of the surveyed young farmers had college degrees — significantly higher than the general population.

The implications for public policy are obvious: promote farming opportunities for young people.

III. Here’s what The National Young Farmers Coalition says in its new report:

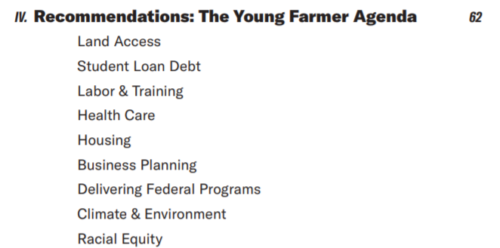

Its agenda:

Now, to make that happen…