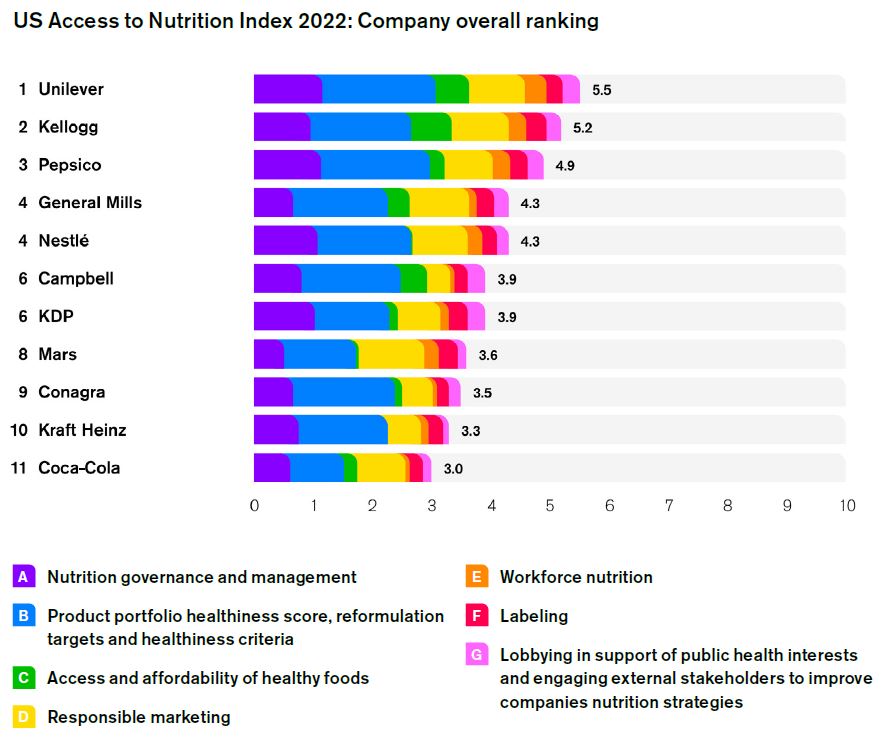

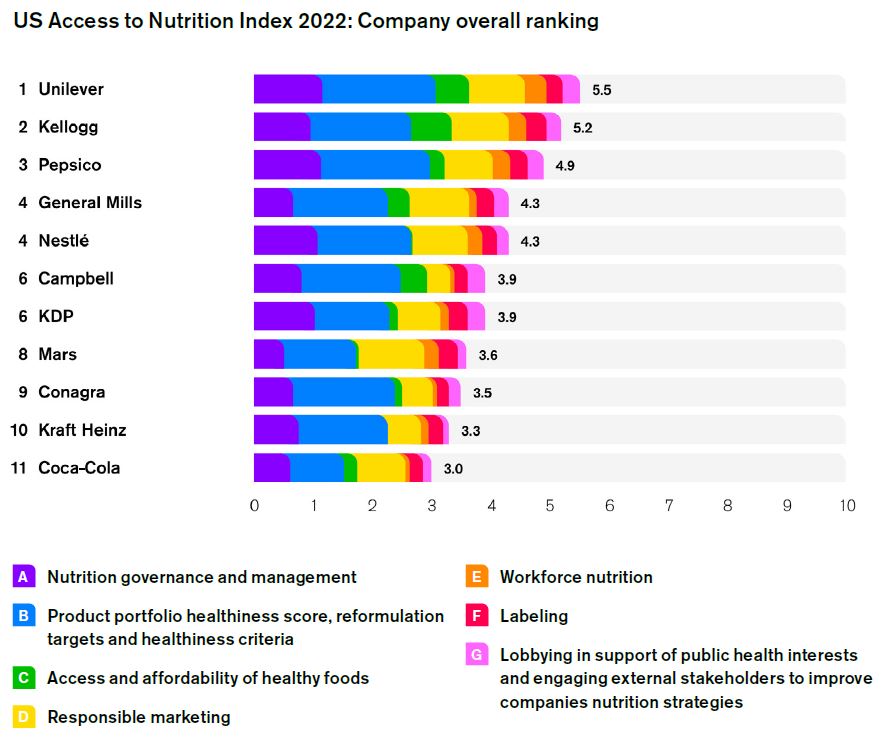

The Access to Nutrition Initiative (ATNI) has released its latest Index report on the progress of the 11 largest U.S. food and beverage companies on their commitments to make, market and sell healthy food and drinks.

The report’s dismal conclusion:

While all companies have placed a greater focus on nutrition in their corporate strategies since the first index was released in 2018, their actual products have not become healthier, and they are not making sufficient efforts to safeguard children from the marketing of unhealthy products.

Collectively, these copanies have sales of about $170 billion annually and account for nearly 30% of all U.S. food and beverage sales.

The report’s overall findings (the Index is a composite on a scale of 10):

Specific findings:

- Only 30% of their products meet criteria for “healthy,” 70% do not. This is only marginally better than in 2018 (see link to my post on this below).

- Companies say they have a greater focus on nutrition and health, but are not doing much about it.

- Only four companies are trying to improve the affordability of their healthier products.

- Companies say they are trying to protect children from the harmful effects of marketing unhealthy products, but they are not doing much about it.

ATNI recommends that companies fix these problems and that the government “support such changes by introducing more effective and enforceable standards and legislation that prevent the marketing of unhealthy products and push companies to apply reformulation strategies on their products.

I like this recommendation, despite its being couched as “encourage,” rather than as a demand:

Companies are encouraged to actively support (and commit to not lobby against) public policy measures in the US to benefit public health and address obesity as enshrined in the National Strategy on food, hunger, nutrition, and health

Comment: Results liket these come as no surprise. To repeat: food companies are not social service or public health agencies; they are businesses with stockholders who demand returns on investment as the first priority.

Expecting companies to change products to make them less attractive or to stop marketing to children means asking them to go against their business interests.

Until companies are rewarded for focusing on social values, public health, and environmental sustainability, ATNI’s evaluations are unlikely to have much of an impact on corporate behavior.

Documents

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.