Response to my conflicts-of-interest post on July 19

On July 19, I did a post on a recent study comparing the nutrient composition of plant-based meat alternatives to that of grass-fed beef. I was not surprised that the study found nutritional differences; they are to be expected.

I was surprised that “From the abstract and conclusion, the study appears to suggest that meat is nutritionally better,” but the authors said the two types “could be viewed as complementary in terms of provided nutrients. It cannot be determined from our data if either source is healthier to consume.” That confused me. I also was confused by the authors’ reported conflicts of interest and said so.

One reader wrote to say that I was being unfair to the authors, who are excellent scientists.

Indeed, the authors followed up with an explanation, which I offered to post here without further comment. They agreed to that.

Dear Dr. Nestle,

Many thanks for posting about our work. We have the utmost respect for your work and we have cited your work in our papers and books (e.g., Provenza’s Nourishment). You are an influential and well-respected person, and as you noted, your followers wanted you to inform them about this paper. When reading the post about our work, we were particularly surprised that you didn’t send us an email to fact-check your points, especially since we were introduced by email on 7/7 that noted: “I’ve copied two of the researchers involved Stephan van Vliet and Fred Provenza. That way if you have any further questions, you can pose those to the researchers directly.” If you disagree, c’est la vie, but at least that would have enabled you to write an informed critique, rather than one that is speculative and, at times, incorrect.

An off-hand and speculative statement such as this one: “maybe the vegetarian was responsible for the hedging comments?” would easily have been addressed by simply sending us an email inquiring about this. We would have gladly told you that it was three of the omnivores (SVV, FDP, SK) who were particularly concerned that people would over extrapolate the data. We were especially concerned that people would interpret our data as beef being “better”. That is not what the data indicate (more on what the data does indicate below). Hence our clear and repeated statement: “It cannot be determined from our data if either source is healthier to consume.”

We are writing you this friendly note to put some context to the points that you made. We hope that you will take them as our attempt to reinforce points that we were careful to develop so our paper was not one-sided.

“So, they’re framing everything with the baseline that animal meat is “proper nutrition” which seems like a pretty obvious bias right out of the gate…”

The two words you quoted are from a much more nuanced sentence, which reads: “This has raised questions of whether plant-based meat alternatives represent proper nutritional replacements to animal meat”. This statement refers to a number of papers by different research groups (see our paper for citations) who pose that very question, which we were interested in exploring. This is much more nuanced statement than what you suggest in the blogpost, which simply states animal meat is “proper nutrition”, which, to us, feels like a twisting of our carefully chosen words.

That we are not framing meat as “proper nutrition” is further illustrated by the stated goal of this work at the end of the introduction: “Given the scientific and commercial interest in plant-based meat alternatives, the goal of our study was to use untargeted metabolomics to provide an in-depth comparison of the metabolite profiles of grass-fed ground beef and a popular plant-based meat alternative, both of which are sometimes considered as healthier and more environmentally friendly sources of “beef”.

Furthermore, we also have to be realistic here and not dance around the obvious; the goal of plant-based meat alternatives is to provide a sensory and nutritional replacement for meat, as illustrated in press releases such as Impossible’s “We are Meat”. If one were to add carotenoids and fiber to a meat sausage (see Arby’s Marrot https://www.foodandwine.com/news/arbys-meat-carrots) and consider this a replacement to a carrot…. We would ask the same question: to what extent do a carrot and a meat-based carrot alternative differ nutritionally? It would be reasonable to take the carrot as the benchmark. All in all, we argue that our framing of the research question is much more nuanced than you suggested in your blogpost. “

To the question of nutritional differences, duh, indeed. Why would anyone not expect nutritional differences? From the abstract and conclusion, the study appears to suggest that meat is nutritionally better.”

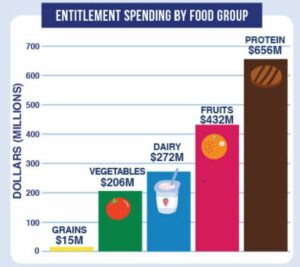

As we acknowledge in the abstract “Important nutritional differences may exist between beef and novel plant-based alternatives; however, this has not been thoroughly assessed.” Please give us some credit. One of us (Fred Provenza) has studied plants and animals for over 50 years. Of course, we expected meat from a cow to differ from meat from soybeans, but the extent to which this may be the case had not been studied. Nor is this clear to the consumer who is simply looking at Nutrition Facts panels, another very important reason why we did the research. Another issue is that foods are often considered equivalent simply based on their protein content (even in dietary guidelines), but “protein foods” can be vastly different in terms of the non-protein nutrients they provide. We recommend Dr. Courtney-Martin’s editorial in AJCN titled “Is a peanut really an egg”. (https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/151/5/1055/6217441). She discusses these issues in such an elegant way.

We do not suggest that meat is nutritionally better, we clearly state the following in the abstract (something you cite in your blogpost): “Amongst identified metabolites were various nutrients (amino acids, phenols, vitamins, unsaturated fatty acids, and dipeptides) with potentially important physiological, anti-inflammatory, and/or immunomodulatory roles—many of which remained absent in the plant-based meat alternative when compared to beef and vice versa. Our data indicates that these products should not be viewed as nutritionally interchangeable, but could be viewed as complementary in terms of provided nutrients. It cannot be determined from our data if either source is healthier to consume.”

The italicized portions are key: we state that some nutrients are not found in the plant-based meat alternative and some nutrients are not found in the meat. Nothing more and nothing less. We also clearly state that we cannot determine from this metabolomics analysis if one is healthier than the other. We intend to pursue that question in research with people, but based on current research we also have to be realistic and we, therefore, highlight the following: “Further work is needed to inform these discussions; however, we consider it important to not lose sight of the “bigger picture” in these discussions, which is the overall dietary pattern in which individual foods are consumed. That is arguably the predominant factor dictating health outcomes to individual foods. Of note is a recent 8-week randomized controlled trial that found that a “flexitarian approach” (swapping moderate amounts of meat with novel plant-based alternatives as part of an omnivorous diet) may have positive benefits in terms of weight control and lipoprotein profiles (e.g., LDL-cholesterol).” (https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa203).

We are not particularly touting the superiority of meat in the discussion. We mention many of the potential health benefits of the compounds found in plant-based meat alternatives such as phytosterols, tocopherols, and other phenolic anti-oxidants, which were more abundant or exclusively found in the plant-based meat alternative.

“Really? If they can’t figure out which is better, why do this study?”

It is not a question of which one is better. It is about understanding potential similarities and differences. Is an almond better than an orange? That depends on the types of nutrients you are looking to get. If you want Vitamin C, an orange is preferred over an almond. If you want Vitamin E, consume the almonds. But there is also nutritional overlap, because both provide fiber and they have complementary phytonutrient profiles. A silly example perhaps when you put it like that, but that’s analogues to what we are stating in the paper.

“As for the conflicted interests: My first reaction to seeing this study was to ask: “Who paid for this?”

No funding was received for this work. The cost of the meat and plant-based meat alternatives (~$600) was paid with my [Dr. Stephan van Vliet] personal credit card (I am a post-doc and had no grant or start-up funds when I first arrived at Duke). The cost of metabolomics (~$200 per sample) was waived by Duke Molecular Physiology Institute’s Metabolomics Core. This was generously done to provide an early career investigator like myself to generate pilot data for a publication and grants.

The North Dakota Beef Association grant that I am the PI on [Dr. Stephan van Vliet] is $135k (not a very big grant) and supports a 4-week RCT that studies cardiovascular risk biomarkers and metabolome profiles in response to eating beef as part of a traditional (whole food) vs standard American diet. Various epidemiological studies suggest that when red meat is consumed as part of a whole foods diet, the associated risk with CVD becomes neutral, whereas eating red meat as part of a standard American diet is associated with increased disease risk. We are testing/falsifying this hypothesis prospectively in a short-term RCT and are exploring potential mechanisms by which this may or may not be the case. This work has nothing to do with plant-based meat alternatives.

The Turner Institute of Ecoagriculture ($27.5k) and the Dixon Foundation ($12.5k) are pilot grants to run metabolomics on grass-fed vs grain-fed bison and beef, respectively. The USDA-NIFA-SARE grant is collecting both plant (crops + fruit) and animal (eggs + beef) food samples from farms that use agroecological principles such as integrated crop-livestock systems. Here we are asking the question: How do practices that potentially stimulate soil health and plant diversity impact the healthfulness of animal and plant foods for human consumption? To be clear, we are also studying crop samples (soy, corn, and peas) some of which may go into alternative protein production.

My [Stephan van Vliet] conflict-of-interest policy is also essentially similar to yours: I accept funding for travel, hotels, meals, and meeting registrations, but I do not accept personal honoraria, consulting fees, or any other financial payments from such groups. A simple email could have cleared that up, but I will make sure that I state this more clearly in future papers.

Of course, we understand the public suspicion about research funding and undue influence. If a certain funding agency doesn’t like the data or the proposal and they don’t want to fund any of our projects then that is what it is, but we would not risk our reputation and career for a few research dollars or to please the funding agency. That’s why we are pushing back on this. Fred Provenza, especially, has been critical of the way beef is produced in confinement feeding operations (e.g., see recent paper https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.547822), so the suggestion that we are beef industry defendants rather than independent scientists does sting a bit.

At the same time, we would also be lying if we didn’t think about where funding comes from. However, the harsh reality is that without foundation/commodity funds for scientific research, there would be much less research, much of which has also proven valuable over time. Even with our USDA grant, one could argue that the reason we are funded is because we wrote a good proposal, but also because our proposed work can presumably benefit the US Farm Bill. Is that true independence? All we know is that we should be transparent (hence our detailed competing interest statement) and let the data speak for itself (hence we attached our full data set as supplementary materials and deposited raw data files on metabolomics workbench), which is what we aimed to do in our Sci Rep paper.

We appreciate your concerns. We will certainly take these into account as we move forward and continue to be critical of our work. We hope you also consider our concerns and are willing to keep an open and friendly dialogue.

Sincerely,

Stephan van Vliet

Fred Provenza

Scott Kronberg