Keeping up with U.S. food politics

It’s not easy to figure out what’s happening on the food front in DC these days, but a lot of it does not sound good. Here are a bunch from last week.

I. Food Bank Support. USDA stops $500 million worth of shipments of food to food banks.

Food banks across the country are scrambling to make up a $500 million budget shortfall after the Trump administration froze funds for hundreds of shipments of produce, poultry and other items that states had planned to distribute to needy residents.

The Biden administration had slated the aid for distribution to food banks during the 2025 fiscal year through the Emergency Food Assistance Program, which is run by the Agriculture Department and backed by a federal fund known as the Commodity Credit Corporation. But in recent weeks, many food banks learned that the shipments they had expected to receive this spring had been suspended.

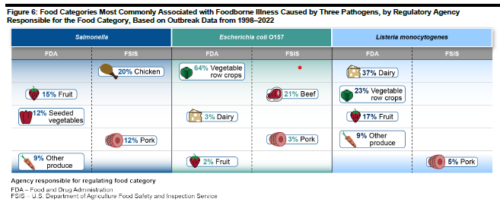

II. Line speeds in meat processing plants. USDA announces “streamlined” meat processing. This is USDA-speak for increasing line speeds in processing plants, something terrifying to anyone who cares about worker safety and food safety. As Food Safety News puts it, this is unsafe at any speed—again.

Once more, policymakers are making the same catastrophic mistake. Once more, industries are downplaying risk while lives hang in the balance. Once more, we are choosing efficiency over responsibility…It’s a reckless increase in processing speeds that threatens to overwhelm the very safeguards meant to protect both workers and consumers.

III. Food safety rules. FDA puts food safety rule on hold

In an announcement on March 20, the Food and Drug Administration said it intends to publish a proposed rule “at a later time.” The rule has already been published and approved and was set to go into effect Jan. 1, 2026. The rule was mandated by the Food Safety Modernization Act, which Congress approved in 2010.

The food industry has been pushing back against the rule since before it was written, citing expenses. Industry groups applauded the FDA’s postponement of enforcement of the rule.

IV. Seed Banks. DOGE is trying to fire staff of the USDA’s National Plant Germplasm System, which stores 62,000 seed samples.

In mid-February, Trump administration officials…fired some of the highly trained people who do this work. A court order has reinstated them, but it’s unclear when they will be allowed to resume their work.

On the other hand, a few useful things are happening.

V. Infant formula. FDA launches “Operation Stork Speed to Expand Options for Safe, Reliable, and Nutritious Infant Formula for American Families. This will involve

- Increased testing for heavy metals and other contaminants.

- Encouragement of companies to develop new infant formulas

- Reviewing baby formula ingredients

- Collaborating with NIH to address research gaps

This is in response to the loss in availability of infant formula due to contamination at an Abbott plant. I don’t see anything in this initiative aimed at enforcing food safety rules in production plants, or anything about the ridiculous pricing of infant formula, which can range four-fold for essentially identical products (all infant formulas have to meet FDA nutrition standards). See: FDA’s main page on Infant Formula.

According to FoodFix, this announcement came after RFK Jr. met with the CEOs of major formula makers, but before Consumer Reports issued a report finding “concerning” levels of heavy metals in some infant formula products.

The FDA’s testing is ongoing. To date, it has completed testing of 221/340 samples, which at this time, do not indicate that the contaminants are present in infant formula at levels that would trigger a public health concern.

VI. Chemical contaminants in food. FDA has published a Chemical Contaminant Transparency Tool. This gives action levels for each contaminant. Presumably, the 221 tests gave results that did not exceed those levels.

Comment

I’m not seeing much about Making America Healthy Again, beyond encouraging the elimination of artificial colors and trying to do something about the GRAS loophole, which lets companies essentially self-determine whether additives are safe. Those are both worth doing, and have been a long time coming. I still want to see this administration take strong action on:

- Ultra-processed food

- Food Safety

- School meals

- Support for small and medium farms

The cancelling of funding for the Diabetes Prevention Program, a 30-year longitudinal study, seems at odds with MAHA. I hope the funding gets restored quicky.