Tonight in Seattle: Slow Cooked in conversation with Dr. Jim Krieger

TODAY: Seattle Town Hall, 7:30 p.m. Information is here.

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

TODAY: Seattle Town Hall, 7:30 p.m. Information is here.

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

TODAY: Petaluma, 140 Kentucky, Copperfield’s Books, 7:00 p.m. Information is here.

**********

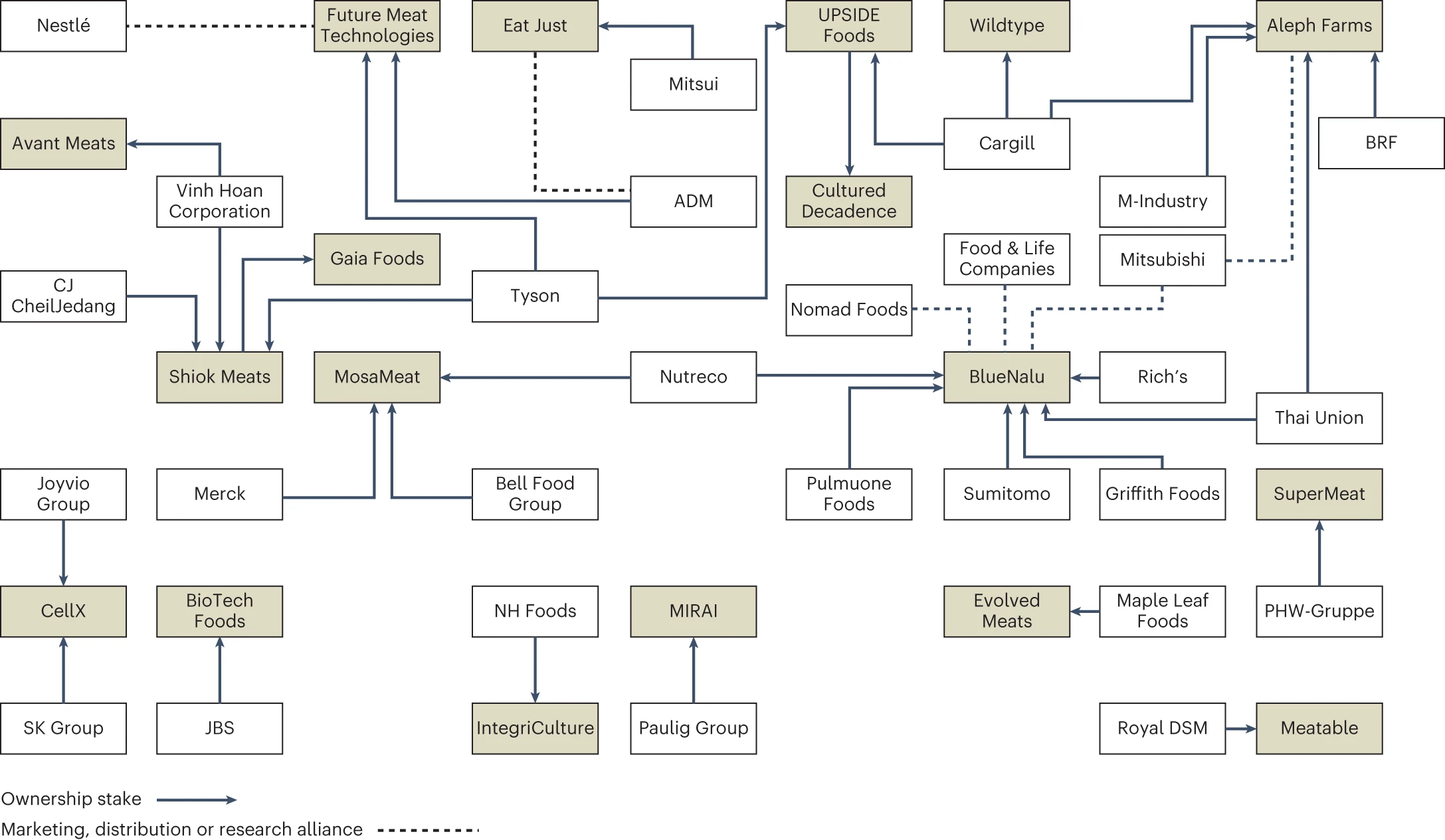

Nature Food has an issue devoted largely to the topic of cell-based meat.

It is worth reading for getting an idea of where current thinking is on this issue, and also because of Phil Howard’s latest take on power on industry the cellular food category.

See his commentary article below.

- Cultured meat needs a race to mission not a race to market, Dwayne Holmes, David Humbird, Jan Dutkiewicz, Yadira Tejeda-Saldana, Breanna Duffy et al.Comment

- A virtue-ethical approach to cultured meat, Carlo Alvaro

- Cultivated meat as a tool for fighting antimicrobial resistance, Eileen McNamara & Claire Bomkamp

- Thick and thin food justice approaches in the evaluation of cellular agriculture, Garrett M. Broad & Robert M. Chiles

- Cellular agriculture will reinforce power asymmetries in food systems, Philip H. Howard

- Challenges of assessing the environmental sustainability of cellular agriculture, Hanna L. Tuomisto

- The triple bottom line framework can connect people, planet and profit in cellular agriculture, Marianne Jane Ellis, Alexandra Sexton, Illtud Dunsford & Neil Stephens

- Transforming a 12,000-year-old technology, Bruce Friedrich

Research Highlight: The price is right for artificial meat, Anne Mullen

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

TODAY: 3:30 pm, lecture followed by a reception. Robertson Auditorium, Mission Bay Conference Center, 1675Owens Street Unit 251. Register here.

**********

FRAC, the Food Research & Action Center, emailed this press announcement: FRAC and More Than 30 National Organizations Urge Senators to Include Provisions to Expand Community Eligibility in Child Nutrition Reauthorization

The groups signed a letter calling for:

Yes!

Here’s what FRAC says about community eligibility:

Community eligibility allows high-need schools to offer free meals to all students at no charge. It reduces administrative work for school districts; allows them to focus on providing healthy and appealing meals to students; supports working families who don’t qualify for free school meals; ensures that all students have the nutrition they need to learn and thrive; and eliminates unpaid school meal fees…Studies have shown participation in school meals improves students’ attendance, behavior, and academic achievement, and reduces tardiness. Students who eat breakfast at school perform better on standardized tests than those who skip breakfast or eat breakfast at home, and have improved scores in spelling, reading, and math.

We had universal school meals during the pandemic. This was:

Universal school meals would save administrative costs. Yes, they would cost more, but not that much more.

And the payoff in kids’ health would be terrific.

This one is a no brainer.

Do it, please.

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

TODAY: San Francisco, Omnivore Books on Food, 3885 Cesar Chavez at Church. Information is here.

*********

I was happy to see this press release from the USDA: Biden-Harris Administration Invests $80 Million to Improve Nutrition in School.

School districts can use the funds to purchase upgraded equipment that will support:

This adds to what this administration is already doing for school meals. It’s an impressive list.

What’s next? Universal school meals, please.

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

TODAY: KPFA book talk in Berkeley. The Back Room, 1984 Bonita Avenue, 7:00 pm. Ticketing info is here.

*****

Jim Krieger, who I will see in Seattle on Saturday, sent this one.

The study: Protocol for a multicentre, parallel, randomised, controlled trial on the effect of sweeteners and sweetness enhancers on health, obesity and safety in overweight adults and children: the SWEET project. BMJ Open. 2022 Oct 12;12(10):e061075. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061075.

Purpose: “The aim of this randomised controlled trial (RCT) is to investigate whether prolonged consumption of sweeteners and sweetness enhancers (S&SEs) within a healthy diet will improve weight loss maintenance and obesity-related risk factors and affect safety markers compared with sugar.”

Competing interests: “AR has received honoraria from Unilever and the International Sweeteners Association. CEH’s research centre provides consultancy to, and has received travel funds to present research results from organisations supported by food and drink companies. JCGH and JH have received project funds from the American Beverage Association. TL works for a company, NetUnion sarl, which has no conflict of interest in the study outcome.”

Comment: This is the official announcement of the research and analysis methods for a new clinical trial. Once the study gets going, it will take a year to get the results. It looks like the trial will be comparing the effects of artificial sweeteners and sugar on body weight and other markers. It is sponsored by a company that makes artificial sweeteners and a trade association for the makers and users of artificial sweeteners. Want to take bets on what the results will look like?

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

Trick or Treat? You can’t make this stuff up. CORRECTION: No you can’t. It’s a fake. Busted.

On the brighter side…

Happy Halloween!

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.

This is too good not to share. I learned about it from this tweet from Simon Boquera at Mexico’s Public Health Institute. It’s a bit over two minutes and aimed at kids.

Wish we had something like this!

Some innovations of the Mexican government healthy eating campaign:

1. Recommends Mexican traditional diet, 2. Physical activity, 3. Hydration with water, 4. Using warning labels to discard #junkfood 5. Avoid sugary drinks and 6. Promote breast feeding pic.twitter.com/wFUUC6UvIY

— Dr. Simón Barquera (@SBarquera) October 23, 2022

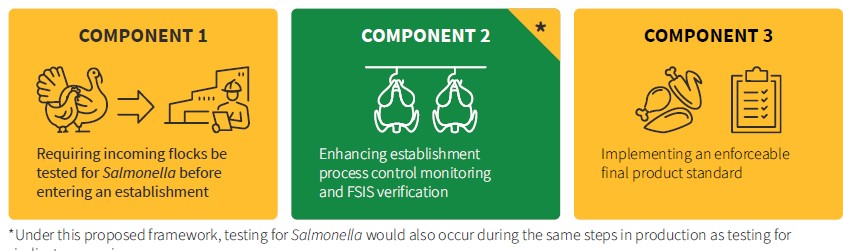

The USDA is at long last giving some attention—a small but significant first step—to reducing Salmonella contamination of poultry products.

Salmonella is a big problem in poultry and eggs. For decades, food safety advocates have called on the USDA to declare Salmonella an adulterant. Adulterated food is illegal to sell.

The poultry industry has resisted, arguing that chicken gets cooked before it is eaten; cooking kills Salmonella.

It does, but you don’t want toxic forms of Salmonella in your kitchen where they can get into other foods. For background all this, see my book, Safe Food: The Politics of Food Safety.

In a press release, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) announces that it

is considering a regulatory framework for a new strategy to control Salmonella in poultry products and more effectively reduce foodborne Salmonella infections linked to these products…The most recent report from the Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration estimates that over 23% of foodborne Salmonella illnesses are attributable to poultry consumption—almost

17% from chicken and over 6% from turkey.

The proposed Salmonalla framework has three components:

What FSIS is actually doing:

We will publish a proposed notice of determination to declare Salmonella an adulterant in NRTE [not ready to eat] breaded and stuffed chicken products in 2022, and we intend to publish additional proposed rules and policies implementing this strategy in 2023, with the goal of finalizing any rules by mid-2024.

The adulterant consideration only applies to breaded and stuffed chicken or turkey products that are likely to be microwaved but not necessarily thoroughly cooked. It does not apply to plain, unbreaded and unstuffed poultry.

Consumer Reports finds lots of poultry to be contaminated with Salmonella. Consumer Reports says Salmonella is “lethal but legal.”

Currently, a chicken processing facility is allowed to have salmonella in up to 9.8 percent of all whole birds it tests, 15.4 percent of all parts, and 25 percent of ground chicken. And producers that exceed these amounts are not prevented from selling the meat. If salmonella became an adulterant, even in some poultry products, it would help reduce the amount of contaminated meat that hits the market.

As might be expected, the National Chicken Council opposes the USDA’s proposed framework: “lacks data, research.”

the facts show that the Centers for Disease Control and FSIS’s own data demonstrate progress and clear reductions in Salmonella in U.S. chicken products. “Increased consumer education about proper handling and cooking of raw meat must be part of any framework going forward…Proper handling and cooking of poultry is the last step, not the first, that will help eliminate any risk of foodborne illness. We’ll do our part to promote safety.”

In other words, the poultry industry wants you to be responsible for protecting yourself against Salmonella. If only you would do a better job of handling and cooking raw chicken. It does not want to have to reduce Salmonella in its flocks in the first place (something quite possible, by the way).

This is a good first step. Let’s urge the USDA to go even further and declare Salmonella an adulterant on all poultry sold in supermarkets.

And maybe require poultry producers to do everything possible to prevent Salmonella geting into flocks in the first place.

This won’t be easy, according to a United Nations report from a recent expert meeting.

The expert consultation noted that no single control measure was sufficiently effective at reducing either the prevalence or the level of contamination of broilers and poultry meat with NT-Salmonella spp. Instead, it was emphasized that control strategies based on multiple intervention steps (multiple or multi-hurdle) would provide the greatest impact in controlling NT-Salmonella spp. in the broiler production chain.

The experts concluded that all of the following approaches were needed:

***********

For 30% off, go to www.ucpress.edu/9780520384156. Use code 21W2240 at checkout.