Mead-Johnson, the company that prides itself on its “decades-long patterning of infant formulas after breast milk,” now goes one better. It sells chocolate- and vanilla-flavored formulas for toddlers, fortified with nutrients, omega-3s, and antioxidants.

The company’s philosophy: Your toddler won’t drink milk? Try chocolate milk!

The company’s philosophy: Your toddler won’t drink milk? Try chocolate milk!

The unflavored version of this product, Enfagrow, has been around for a while. In 2005, nutritionists complained about this formula because it so evidently competed with milk as a weaning food. Mead-Johnson representatives explained that Enfagrow is not meant as an infant formula. It is meant as a dietary supplement for toddlers aged 12 to 36 months.

Really? Then how come it is labeled “Toddler Formula”?

And how come it has a Nutrition Facts label, not a Supplement Facts label?

Here’s the list of ingredients for everything present at a level of 2% or more:

- Whole milk

- Nonfat milk

- Sugar

- Cocoa

- Galactooligosaccharides (prebiotic fiber)

- High oleic sunflower oil

- Maltodextrin

I bought this product at Babies-R-Us in Manhattan. It’s not cheap: $18.99 for 29 ounces. The can is supposed to make 22 servings (one-quarter cup of powder mixed with 6 ounces water). At that price, you pay 86 cents for only six ounces of unnecessarily fortified milk plus unnecessary sugar and chocolate.

No wonder Jamie Oliver encountered so much grief about trying to get sweetened, flavored milks out of schools.

But really, aren’t you worried that your baby might be suffering from a chocolate deficit problem? Don’t you love the idea of year-old infants drinking sugar-sweetened chocolate milk? And laced with “omega-3s for brain development, 25 nutrients for healthy growth, and prebiotics to support the immune system”?

Next: let’s genetically modify moms to produce chocolate breast milk!

FDA: this package has front-of-package health claims clearly aimed at babies under the age of two. Uh oh. Shouldn’t you be sending out one of those package label warning letters to Mead-Johnson on this one?

Addition, May 1: in response to interest in what other products are made by Mead-Johnson, or its parent, the drug company Bristol-Myers Squibb, I’ve linked their names to product pages.

Addition, May 6: Julie Wernau of the Chicago Tribune did a front page (business section) story on this and is following up on it in her blog.

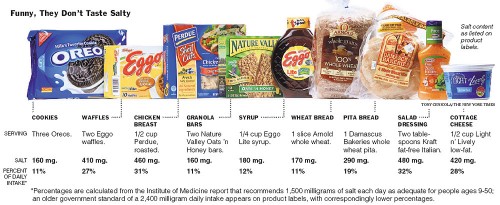

To translate the numbers, recall that salt is 40% sodium. This means that 400 mg sodium = one gram of salt, 200 mg sodium = half a gram of salt, and 4 grams of salt = 1 teaspoon.

To translate the numbers, recall that salt is 40% sodium. This means that 400 mg sodium = one gram of salt, 200 mg sodium = half a gram of salt, and 4 grams of salt = 1 teaspoon.

The company’s philosophy: Your toddler won’t drink milk? Try chocolate milk!

The company’s philosophy: Your toddler won’t drink milk? Try chocolate milk!