The ever curious Kerry Trueman, Eating Liberally’s kat, wants to hear more about Bloomberg’s salt assault. And well she might. Today’s New York Times has a bunch of letters weighing in from all points of view. Here’s how our conversation went:

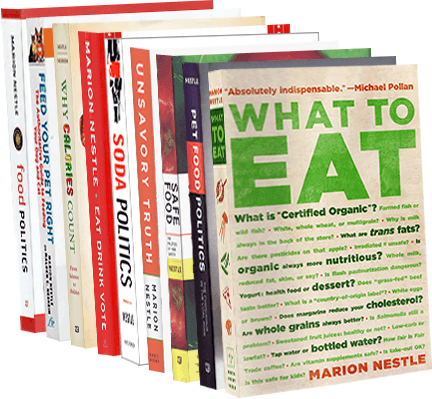

(With a click of her mouse, EatingLiberally’s kat corners Dr. Marion Nestle, NYU professor of nutrition and author of Pet Food Politics, What to Eat and Food Politics🙂

Kat: New York City’s new initiative to persuade food manufacturers and restaurants to voluntarily reduce the salt in their foods by 25% over the next five years is eliciting the usual outrage from the “nanny state” naysayers, for whom excess salt consumption is yet another matter of personal responsibility.

But as you noted last Monday, “nearly 80% of salt in American diets is already in packaged and restaurant foods and if you eat them at all you have no choice about the amount of salt you are getting.” Many Americans consume more than double the daily recommended intake of sodium, contributing to thousands of deaths and billions in medical costs annually.

Mayor Bloomberg equates the food industry’s overuse of salt to such health hazards as asbestos. But Mark Kurlansky, author of Salt: A World History, insisted to WNYC’s Amy Eddings that this analogy is false because “we could reduce our salt intake on our own, if we wanted to.”

Technically, this is true, if you’re willing and able to eliminate packaged foods from your diet, stop eating out, and start cooking all your meals from scratch. Unfortunately, the percentage of folks who have the time, inclination, and resources to do this is roughly on a par with those who think that Wall Street’s robber barons earned those big bonuses.

The food industry maintains that it would gladly reduce the sodium in its products–and some are doing so surreptitiously–if only consumers conditioned to crave super salty foods would be more willing to accept reduced sodium products.

The “invisible hand” of the market can’t seem to let go of the salt shaker. Mayor Bloomberg’s proposal is a step in the right direction, but do you think it will achieve meaningful reductions, or will we ultimately end up having to regulate salt?

Dr. Nestle: I love nanny-state accusations. Whenever I hear them, I know either that food industry self-interest is involved or that the accuser really doesn’t understand that our food system already is government-regulated as can be. These kinds of actions are just tweaking of existing policy, in this case to promote better health.

At issue is the default. Right now, companies have free rein to add as much salt to their processed or prepared foods as they like. The makers of processed foods do focus-group testing to see how consumers like the taste of their products. They invariably find that below a certain level of salt–the “bliss” point—their study subjects say they don’t like it. Soups are a good example. A measly half-cup portion of the most popular Campbell’s soups contains 480 mg of sodium or more than a full gram of salt (4 grams to a teaspoon).

To someone like me who has been trying to reduce my salt intake for years, those soups taste like salt water. That’s because the taste of salt depends on how much you are eating. If you eat a lot, you need more to taste salty. If you are like me, practically all processed and restaurant foods taste unpleasantly salty.

So what to do? I say this is indeed a matter of personal choice and right now I don’t have one. If I want to eat out at all, I know I’m going to feel oversalted by the time I get home.

I want the default choice to be lower in salt. Nobody is stopping anyone from salting food. You don’t think your food tastes salty enough? Get out the salt shaker.

But let me make two other comments. One is that the amount of salt we eat is so far in excess of what we need that asking food makers and sellers to cut down can hardly make a dent in taste. A new Swedish study just out says that young men consume at least twice the salt they need and the authors are calling on government to require food makers to start cutting down.

And yes, the science is controversial and not everyone has blood pressure that goes through the roof when they eat something salty. But lots of people do. And almost everyone has blood pressure that goes up with age. As a population, we would be better off exposed to less salt in our diets.

Some food makers are already gradually cutting down on salt, but quietly so nobody notices. If every food company were required to do that, everyone would get used to a less salty taste and we all might be able to better appreciate the subtle tastes of food.

My guess is that Bloomberg has started a movement and we will be seeing much more effort to lower the salt intake of Americans. As I see it, this is about giving people a real choice about what they eat.

Correction, January 22: Juli Mandel Sloves of Campbell Soup correctly points out that I am in error. A serving of soup is 8 ounces, not 4, even though the label says that a serving is half a cup. How come? Because the can is to be diluted with another can of water, making it 21 ounces divided by 2.5 servings per can, or about 8 ounces. Complicated, no? But this means the sodium content is 480 mg per cup, not half cup, despite what the label says. I apologize for the error. But here is an excellent reason to redesign the Nutrition Facts label, alas.