Another update on CBD and marijuana edibles (and drinkables)

I’m trying to keep up with what’s happening with Cannabis edibles and drinkables, still with borderline legality in most places, but gradually working their way to supermarkets near you.

Here’s what’s come up lately.

- The FDA is calling a public hearing on May 31 and asking for comments on Cannabis products.

- The Washington Post discusses the messy regulatory situation.

- Cannabidiol (CBD), extracted from hemp, does not have the psychoactive properties of marijuana.

- The 2018 Farm Bill legalized the raising of hemp, which contains CBD.

- On the local level: regulators in different agencies view regulation in different ways.

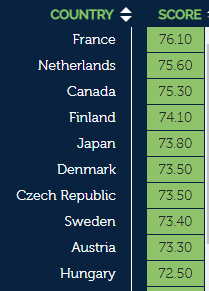

- On the global level: different countries are handling regulation of these products in different ways.

- CVS will be selling CBD products as over-the-counter drugs.

- As for edibles, CBD-infused water is predicted to be the big seller.

- The Sacramento Bee reported what happens when kids get into their parents’ marijuana edibles; it called for childproof packaging.

- A video from Fresno County shows unlicensed marijuana edibles, some of which look like candies aimed at children.

- The FDA will hold a public hearing on the safety, manufacturing, quality, marketing, labeling, and sale of Cannabis products on May 31.

And then there are the health claims. As early as 2017, the FDA sent out warning letters to makers of CBD products; they were marketing their products as drugs not supplements or foods.

For example, the FDA sent a letter to That’s Natural, complaining that the company published testimonials saying things like this:

- “Scientific research by doctors have shown it actually kills cancer cells and provides a protective coating around our brain cells.”

- “as a Type 1 diabetic, my blood sugars have noticeably leveled off.”

- “My blood pressure and heart rate have also significantly improved as well.”

The FDA also sent a letter to Green Roads of Florida objecting to claims like these:

- “CBD .[has] anti-proliferative properties that inhibit cell division and growth in certain types of cancer, not allowing the tumor to grow.”

- “Almost all studies recognize CBD’s potential in preventing both cancer spread and growth…”

- “The following are some of the many ailments CBD oil can potentially be therapeutic for: asthma, Alzheimer’s disease, arthritis, autism, bipolar disorder, various types of cancer….

Food, medicine, supplement, or snake oil? We shall see.