My post yesterday about Michele Simon’s report on food company sponsorship of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) elicited a wealth of thoughtful comments. These are well worth careful consideration.

Many express disappointment that I would suggest that corporate sponsorship might influence their thinking or practice, that other nutrition professionals have equal or better education, that I singled out AND when other nutrition and health organizations also accept food industry funds, or that I am unsympathetic to their plight (they are required to be AND members whether or not they agree with its policies).

Let me clarify:

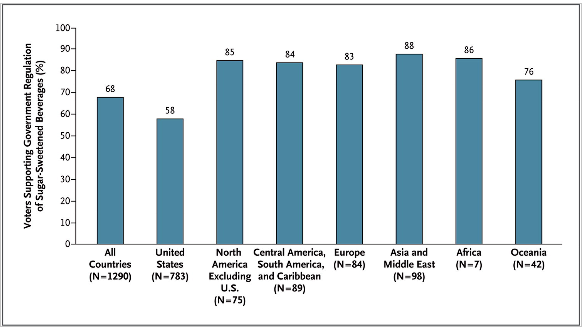

On the effects of corporate sponsorship: I don’t know a single individual who thinks that taking money from food companies influences personal opinion or practice, but research on the effects of drug—and food—company sponsorship demonstrates otherwise. At the very least, sponsorship gives the appearance of conflict of interest. Individuals and organizations who accept sponsorship from soda companies, for example, can hardly be expected to advise the public to drink less soda.

On education: my point here is not that dietetic education is inadequate but that other nutritionists without such training may be equally qualified to advise the public about diet and health.

On other organizations: That other nutrition and health organizations accept funds from food companies has long been a point of discussion on this blog (click on Partnerships). I am especially concerned about the practices of the American Society of Nutrition, to which I belong. Its embarrassing role in the Smart Choices fiasco was an example of why nutrition professional organizations should avoid getting involved in such alliances.

On sympathy: I have plenty. Food company sponsorships create painful dilemmas for nutrition professionals and each of us must figure out our own way to deal with them. I have written about my own struggles with this issue in Food Politics and elsewhere.

I especially appreciate the comments from those of you engaged in your own struggles with this issue within AND. You have your work cut out for you. Here, for example, is the response of your president, Dr. Ethan Bergman, to Simon’s report. He writes [and see addition below]:

There is one indisputable fact in the report about the Academy’s sponsorship program: We have one. And for the record, I support the Academy’s sponsorship program, as does the Board of Directors and our members.

Let me make it clear that the Academy does not tailor our messages or programs in any way due to influence by corporate sponsors and this report does not provide evidence to the contrary.

…As members of a science-based organization, I encourage you to not take all information you see at face value, always consider the source (in this case, an advocate who has previously shown her predisposition to find fault with the Academy) and seek out the facts.

My interpretation: ignore the message because the messenger is not one of us.

As nutrition professionals, we ignore such messages at our peril. If we want the public to trust what we say, our views cannot be perceived as compromised by financial ties to food companies.

What you can do. If, as some of you noted, you oppose corporate sponsorship and would like to do something about it, here are a few suggestions:

- Let your voice be heard: write letters, post blogs, send tweets.

- Make it clear to colleagues and clients that you oppose current policies on corporate sponsorship.

- Provide evidence that your organization can do just fine without the money.

- Join committees and groups within your organization; say what you think.

- Organize petition campaigns.

- Run for office; run a slate for office.

If you want the policy to change, work for it.

But don’t be discouraged if nothing much happens right away. Change takes time. Keep at it.

Thanks to all of you for taking this issue so seriously. Let’s keep working together to find ways to keep food company money out of our professional lives.

Addition, January 25: a reader, Craig, points out that Coca-Cola gave Dr. Bergman the opportunity to carry the torch at last summer’s Olympic games. A news story about this event quotes Dr. Bergman on the Academy’s partnership:

I think the philosophy that Coca Cola has through its Live Positively campaign, and our philosophy at the academy, is about trying to improve the nation’s health through better nutrition and fitness so this fits in well with our cause.