Ultra-processed pushback #4: a debate

The British journal, Public Health Nutrition, published a debate about ultra-processed foods this month.

Invited commentaries

CON: Michael Gibney. Ultra-processed foods in public health nutrition: the unanswered questions,

Several definitions of the degree of processing have been proposed. However, when each of these is used on a common database of nutritional, clinical and anthropometric variables, the observed effect of high intakes of highly processed food, varies considerably.. Moreover, assigning a given food by nutritional experts, to its appropriate level of processing, has been shown to be variable. Thus, the subjective definitions of the degree of food processing and the coding of foods according to these classifications is prone to error…Another issue that need[s] resolution is the relative importance of the degree of food processing and the formulation of a processed food. Although correlational studies linking processed food and obesity abound, there is a need for more investigative studies.

PRO: Mark Lawrence. Ultra-processed foods: a fit-for-purpose concept for nutrition policy activities to tackle unhealthy and unsustainable diets. Also an addendum: Ultra-processed foods: a fit-for-purpose concept for nutrition policy activities to tackle unhealthy and unsustainable diets.

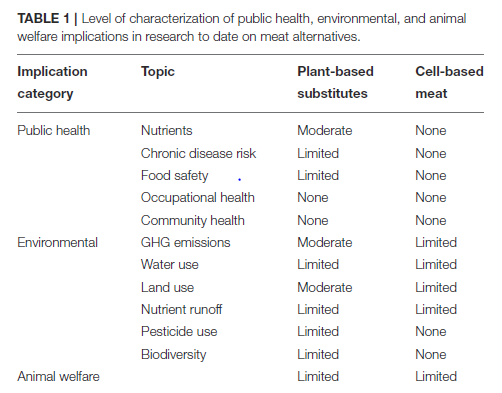

This commentary describes the UPF concept as being fit-for-purpose in providing guidance to inform policy activities to tackle unhealthy and unsustainable diets. There is now a substantial body of evidence linking UPF exposure with adverse population and planetary health outcomes. The UPF concept is increasingly being used in the development of food-based dietary guidelines and nutrition policy actions. It challenges many conventional nutrition research and policy activities as well as the political economy of the industrial food system. Inevitably, there are politicised debates associated with UPF and it is apparent a disproportionate number of articles claiming the concept is controversial originate from a small number of researchers with declared associations with UPF manufacturers.

Letters to the editor

CON: Mark J Messina, John L Sievenpiper, Patricia Williamson, Jessica Kiel, John W Erdman. Ultra-processed foods: a concept in need of revision to avoid targeting healthful and sustainable plant-based foods

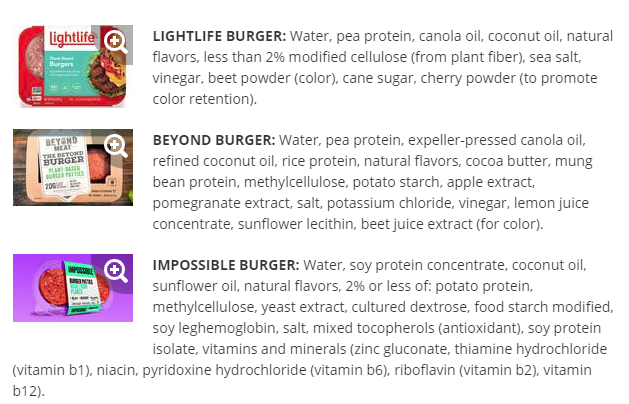

we take issue with his perspective on our recently published article in which we make two fundamental points. First, the common criticisms of ultra-processed foods (UPF) do not apply to soya-based meat and dairy alternatives more so than they do to their animal-based counterparts, meat and cows’ milk, despite the former being classified as UPF and the latter as unprocessed/minimally processed foods. Second, NOVA is overly simplistic and does not adequately evaluate the nutritional attributes of meat and dairy alternatives based on soya….We therefore stand by our opinion that NOVA does a disservice to the public by suggesting that because soya burgers and soyamilk are NOVA-classified as UPF, they should be avoided. These foods can aid in the transition to and maintenance of plant-based diets.

PRO: Mark Lawrence. The need for particular scrutiny of claims made by researchers associated with ultra-processed food manufacturers.

In this Commentary, I referred to challenges the UPF concept presents to researchers with declared associations with UPF manufacturers. The interplay between nutrition research and commercial interests is a widely recognised phenomenon in the commercial determinants of health literature…UPF-related research has become highly politicised and the integrity of the claims presented by researchers associated with UPF manufacturers demands close scrutiny.

Comment

In his letter, Mark Lawrence noted my having included the paper by Messina et al as one of my “industry-funded studies of the week” on this website. In it, I reproduced the unusually long conflict of interest declaration of the authors, many of them disclosing ties to companies making ultra-processed foods. Again, the ultra-processed concept is backed up by an extraordinary amount of research far beyond the point where it can be ignored or dismissed out of hand.

Professor Lawrence explains why there is so much pushback: “It [the UPF concept] challenges many conventional nutrition research and policy activities as well as the political economy of the industrial food system.”