Daniel Green, a student at Cornell, asked whether I intended to write about Paul Ryan’s views on food politics. He volunteered to put something together with his colleague, Dr. Margaret Yufera-Leitch. Here are their thoughts:

Few Americans had heard of Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin) until last week when he was announced as Presidential-hopeful Mitt Romney’s November running mate. A Janesville, Wisconsin native, former personal trainer and Oscar Mayer Weinermobile driver during his college days, Ryan is a strong advocate on the Hill for the P90x exercise routine and avoids eating fried foods and desserts (yes, even on the campaign trail).

But how do Mr. Ryan’s personal beliefs impact his voting on food politics related matters?

Obesity prevention

In the case of obesity, prevention has been shown repeatedly to be the best medicine. Of the $2.6 trillion spent on US health care in 2010, 95% went for disease treatment leaving only $421 per American per year for prevention—not even enough money for a 1-year gym membership in most states.

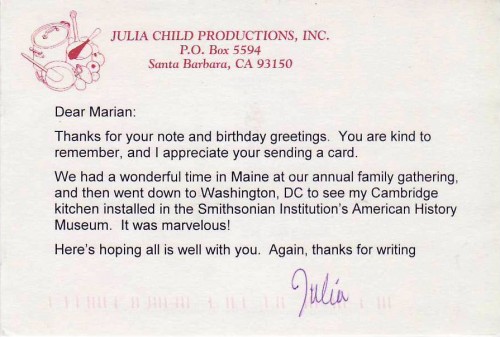

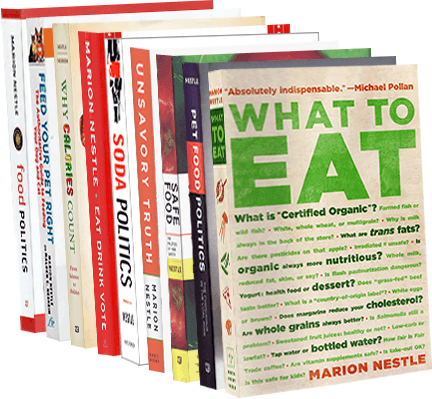

In an interview with Politico, Mr. Ryan admitted to maintaining 6-8% body fat with a healthy BMI of 21, admirable for any working professional. But Mr. Ryan, who has voted against every Affordable Care Act related bill, takes the stance that what you eat and what you weigh are both matters of personal responsibility. In 2005, he voted for H.R. 554 “The Personal Responsibility in Food Consumption Act” also known as the cheeseburger bill, which aimed to ‘prohibit weight gain-related or obesity-related lawsuits from being brought in federal or state courts against the food industry.’ The bill was passed by the House but failed to even go up for vote in the Senate. The legislation was featured in the 2004 Morgan Spurlock documentary Super Size Me, where Marion Nestle also made her on-screen debut.

According to a recent report by the Bipartisan Policy Center, by 2020 Obesity will cost America $4.6 trillion dollars annually and healthcare costs related to obesity will consume 19.8% of U.S. GDP. The sudden rise of obesity is a clear sign that, as a country, we have fostered an obesogenic environment that will require commitments from both the public and private sectors to reform.

Given that 70% of Americans are overweight and obese, we have collectively demonstrated that public service announcements alone have not yet resulted in the significant population-wide behavior changes needed to reverse obesity and more importantly alleviate a strained U.S. Health Care system.

SNAP Benefits

One of the most important programs available to lower income Americans is the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly referred to as Food Stamps, which provides access to fresh foods for low-income families. Given that increased fruit and vegetable consumption are cornerstone habits of the Preventative Medicine conversation, why has Mr. Ryan argued to cut SNAP by $33 billion over the next ten years?

Affordable Care Act

Paul Ryan’s choices to repeal $6.2 trillion dollars of support from the Affordable Care Act and obesity-related provisions, demonstrates a lesser degree of support for preventative care than his widely publicized exercise regime suggests. Perhaps with unemployment still high and unsure economy, America has bigger fish to fry than fixing the food system and reversing obesity but at least for now, Paul Ryan will take his fish broiled.

Paul Ryan Food Politics Fact Sheet

| Favorite Exercise Program: |

P90x |

| BMI: |

21 (Healthy) |

| Dietary Restrictions: |

Doesn’t eat desserts or fried foods |

| View on cause of Obesity |

Personal Responsibility |

| Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) |

For |

| Farm Bill |

Against |

| Food Safety Modernization Act |

Against |

| Healthcare Reform (Affordable Care Act/Obamacare) |

Strongly against |

| Menu Labeling |

No direct comment- but against Obamacare which includes it |

| Repealing the Prevention and Public Health Fund |

For |

| School Lunch Reform and Child Nutrition Reauthorization |

For |

| Soda Taxes |

No direct comment |

References and source materials are available from the authors:

- Daniel Green studies Applied Nutrition and Psychology at Cornell University. dpg64@cornell.edu. You can follow him on Twitter at www.Twitter.com/dgrreen.

- Margaret Yufera-Leitch received her PhD in experimental psychology with a focus in eating behavior from the University of Sussex. She is currently a visiting assistant professor at the University of Calgary. dr.leitch@impulsive-eating.com. Her website is www.impulsive-eating.com.