Kerry Trueman: Has politics always had such a huge impact on the way we eat?

Marion Nestle: Of course it has. As long as we have had inequities between rich and poor, politics has made some people fat while others starved. Think, for example, of the sugar trade and slavery, the Boston tea party, or the role of stolen bread in Les Misérables. Bread riots and food fights are about politics. But those events seem simple compared to what we deal with now, when no food issue seems too small to generate arguments about who wins or loses. Congressional insistence that the tomato paste on pizza counts as a vegetable serving is only the most recent case in point.

KT: How do you reconcile the fact that what’s good for us as individuals–namely, eating less junk food–is bad for business?

MN: I don’t think these facts are easily reconciled. They can only be observed and commented and acted upon. The job of the food industry is to produce products that will not only sell well, but will sell increasingly well over time, in order to produce growing returns to investors. Reconciliation requires companies either to sell less (impossible from a business standpoint) or make up the difference with sales of healthier products. Unfortunately, the so-called healthier products–and whether they really are is debatable–rarely sell as well. In practice, companies touch all bases at once: they put most marketing efforts into their core products, they proliferate new better-for-you

products, and they seek new customers for their products among the vast populations of the developing world–where, no surprise, the prevalence of obesity is increasing, along with its related diseases.

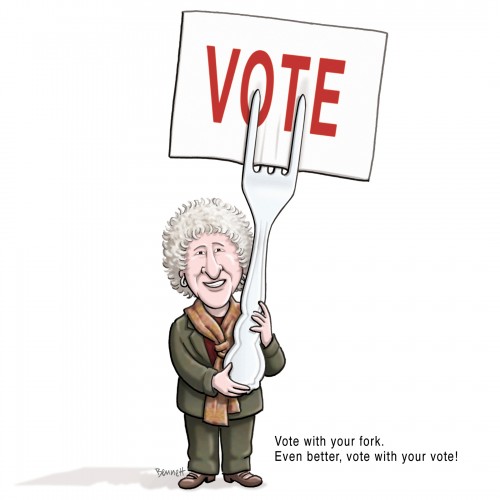

KT: Why did you want to do a book of food politics cartoons?

MN: If truth be told, I’ve been wanting to do one for years. Cartoons are such a great way to engage audiences. Politics can be dreary. Cartoons make it fun. I’ve collected cartoons for years on everything about food and nutrition. I would have loved to do a book on nutrition in cartoons but getting permission to reprint them was too difficult and expensive. For the cartoons in my last book, Why Calories Count, I contacted the copyright holder, Sara Thaves, who represents the work of about 50 cartoonists. During our negotiations about how much they would cost, Sara asked if I might be interested in doing a book using Cartoonist Group cartoons. Would I ever! Sara ended up sending me more than 1,100 cartoons–all on food politics. I put them in categories and started writing. The only hard part was winnowing the drawings to a publishable number. But what a gorgeous book this turned out to be! The cartoons are in full color.

KT: In Eat Drink Vote, you note that, it ought to be possible to enjoy the pleasures of food and eat healthfully at the same time.

Why does that ideal meal elude so many of us?

MN: Because our food choices are so strongly influenced by the food environment. Given a large plate of food, for example, practically everyone will eat more from it than from a smaller portion. And then there’s the cooking problem. For decades, Americans have been told that cooking is too much trouble and takes too much time. As a result, many people would rather order in and wait for it to arrive and get heated up again than to start from scratch. And healthy foods cost more than highly processed junk foods, and not only on the basis of calories. The government supports the production of corn and soybeans, for example, but not that of broccoli or carrots. I should also mention that food companies get to deduct the cost of marketing, even marketing to children, from their taxes as legitimate business expenses.

KT: On the subject of food and pleasure, you enjoy the occasional slice of pizza or scoop of ice cream, just as Michelle Obama loves her french fries. Do you subscribe to the all things in moderation

philosophy, or are there some things you simply won’t eat, ever?

MN: The only food I can think of that I won’t ever eat is brains, and that’s rarely a problem. And yes, I do subscribe to everything in moderation

although it’s hard to admit it without irony. The phrase has been so misused by food companies and some of my fellow nutritionists to defend sales of junk foods and drinks. There is no question that some foods are healthier to eat than others and we all would be better off eating more of the healthier ones and fewer of the less healthful foods. But fewer

does not and should not mean none.

And what’s wrong with pizza, pray tell? In my view, life is too short not to leave plenty of room for freshly baked pizza, toffee candy, real vanilla ice cream, and a crusty, yeasty white bread–all in moderation, of course.