Here’s my monthly (first Sunday) Food Matters column from the San Francisco Chronicle. The question (edited) came from a reader of this blog.

Q: You view New York City’s cap on any soda larger than 16 ounces as good for public health. I don’t care if sodas are bad for us. The question is “Whose choice is it?” And what role should the nanny state play in this issue?

A: Your question comes up at a time when the New York State Supreme Court is hearing arguments about whether New York City’s health department has the right to establish a limit on soda sizes.

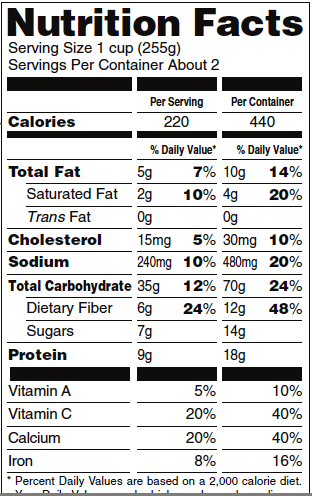

As an advocate for public health, I think a soda cap makes sense. Sixteen ounces provides two full servings, about 50 grams of sugars, and 200 calories – 10 percent of daily calories for someone who consumes 2,000 calories a day.

That’s a generous amount. In the 1950s, Coca-Cola advertised this size as large enough to serve three people.

You may not care whether sodas are bad for health, but plenty of other people do. These include, among others, officials who must spend taxpayer dollars to care for the health of people with obesity-related chronic illnesses, employers dealing with a chronically ill workforce, the parents and teachers of overweight children, dentists who treat tooth decay, and a military desperate for recruits who can meet fitness standards.

Poor health is much more than an individual, personal problem. If you are ill, your illness has consequences for others.

That is where public health measures come in. The closest analogy is food fortification. You have to eat vitamins and iron with your bread and cereals whether you want to or not. You have to wear seat belts in a car and a helmet on a motorcycle. You can’t drive much over the speed limit or under the influence. You can’t smoke in public places.

Would you leave it up to individuals to do as they please in these instances regardless of the effects of their choices on themselves, other people and society? Haven’t these “nanny state” measures, as you call them, made life healthier and safer for everyone?

All the soda cap is designed to do is to make the default food choice the healthier choice. This isn’t about denial of choice. If you want more than 16 ounces, no government official is stopping you from ordering as many of those sizes as you like.

What troubles me about the freedom-to-choose, nanny-state argument is that it deflects attention from the real issue: the ferocious efforts of the soda industry to protect sales of its products at any monetary or social cost.

The lawsuit against the soda cap is a perfect example. It is funded by the American Beverage Association, the trade association for Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and other soft-drink companies, at what must be astronomical expense.

To confuse the public about corporate profits as a motive, the beverage association enlisted two distinguished civil rights groups – the NAACP and the Hispanic Federation – to file an amicus brief on behalf of its lawsuit.

Never mind that the obesity rate for the communities these groups represent is considerably higher than average in New York City, and that these neighborhoods would benefit most from the soda cap. The amicus brief argues that the soda cap discriminates against them.

The brief, however, neglects to mention that both amicus groups received large donations from soda companies and that the NAACP in particular has a long history of partnership with Coca-Cola.

Financial arrangements between soda companies and ostensibly independent groups demand scrutiny. National and local reporters – bless them – have done just that.

They report, among other connections, that one of the law firms working for Coca-Cola wrote the amicus brief, and that a former president of the Hispanic Federation just took a job with that company.

Last fall, the East Bay Express exposed how the soda industry exploited race issues to divide the electorate and defeat the Measure N soda tax initiative in Richmond. It revealed

that the beverage association not only paid for the successful “grassroots” campaign against Measure N but also encouraged views of the soda tax as racist.

Driven by this experience, the soda industry is repeating this tactic in New York City.

Is a cap on soda sizes discriminatory against groups working for civil rights? Not a chance.

Public health measures are about alleviating health disparities and giving everyone equal access to healthy diets and lifestyles. This makes public health – and initiatives like the soda cap – broadly inclusive and democratic.

If anything is undemocratic and elitist, it is suing New York City over the soda cap.

In funding this lawsuit, the soda industry has made it clear that it will go to any length to protect its profits, even if it means discrediting the groups that would most benefit from this rather benign public health initiative.