I was asked by Time Magazine to write a comment on the soda industry’s recent promises. It was posted yesterday.

The Soda Industry’s Promises Mean Nothing

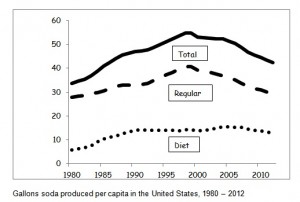

Agreeing to decrease soda consumption by 20 percent is easy to do when demand is already falling rapidly

–Marion Nestle, September 30, 2014

The recent pledge by Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and the Dr Pepper Snapple Group to reduce calories that Americans consumd from their products by 20 percent by 2025 elicited torrents of praise from the Global Clinton Initiative, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the national press.The real news: soda companies are at last admitting their role in obesity.Nevertheless, the announcement caused many of us in the public health advocacy community to roll our eyes. Once again, soda companies are making promises that are likely to be fulfilled anyway, whether the companies take any action or not.

Americans have gotten the word. Sodas in anything but small amounts are not good for health.

Although Coca-Cola and the American Beverage Association have funded studies that invariably find sodas innocent of health effects, the vast preponderance of research sponsored by the government or foundations clearly demonstrates otherwise.

Think of sodas as candy in liquid form. They contain astonishing amounts of sugars. A 12-ounce soda contains 10 (!) teaspoons of sugar and provides about 150 calories.

It should surprise no one that adults and children who habitually consume sugary drinks are far more likely to take in fewer nutrients, to weigh more, and to exhibit metabolic abnormalities compared to those who abstain or drink only small amounts.

And, contrary to expectation, diet sodas don’t seem to help. A widely publicized recent study suggests that artificially sweetened drinks affect intestinal bacteria in ways, as yet undetermined, that lead to metabolic abnormalities–glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. This research is largely animal-based, preliminary, and requires confirmation. But one thing about diet drinks is clear: they do not do much good in preventing obesity.

People who drink diet sodas tend to be more obese than those who do not. The use of artificial sweeteners in the United States has gone up precisely in parallel with the rise in prevalence of obesity. Is this a cause or an effect? We don’t know yet.

While scientists are trying to sort all this out, large segments of the public have gotten the message: stay away from sodas of any kind.

Since the late 1990s, U.S. per capita consumption of soft drinks has dropped by about 20 percent. If current trends continue, the soda industry should have no trouble meeting its promise of another 20 percent reduction by 2025.

Americans want healthier drinks and are switching to bottled water, sports drinks, and vitamin-fortified drinks—although not nearly at replacement levels. The soda industry has to find ways to sell more products. It also has to find ways to head off regulation. Hence: the promises.

To deal with sales shortfalls, the leading soft-drink brands, Coca-Cola and Pepsi, have expanded their marketing overseas. They have committed to invest billions to make and promote their products in Latin America as well as in the hugely populated countries of Asia and Africa where soda consumption is still very low.

From a public health standpoint, people everywhere would be healthier—perhaps a lot healthier—drinking less soda.

In California, the cities of San Francisco and Berkeley have placed soda tax initiatives on the November ballot. The American Beverage Association, the trade association for Coke, Pepsi, and the like, is funding anti-tax campaigns that involve not only television advertising and home mailings, but also creation of ostensibly grassroots (“astroturf”) community organizations, petition campaigns, and, when all else fails, lawsuits to make sure the initiative fails. These efforts are carbon copies of the tactics used to defeat New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s portion size cap proposal.

If the soda industry really wants to help prevent obesity, it needs to change its current practices. It should stop fighting tax and size initiatives, stop opposing warning labels on sugary drinks, stop lobbying against restrictions on sodas in schools, stop using sports and music celebrities to sell products to children, stop targeting marketing to African-American and Hispanic young people, and stop funding research studies designed to give sodas a clean bill of health.

And it should stop complaining, as PepsiCo’s CEO Indra Nooyi didlast week, that nobody is giving the industry credit for all the good it is doing.

If the government really were serious about obesity prevention, it could ban vending machines from schools, set limits on the size of soft drinks sold at school events, define the amount of sugars allowable in foods and beverages, and, most of all, stop soda marketing aimed at children of any age.

Because neither the soda industry nor the government is likely to do any of this, public health advocates still have plenty of work to do.

Marion Nestle is professor of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University. She is currently working on a book titled Soda! From Food Advocacy to Public Health.