What’s up with the retraction of the Séralini feeding-GMO-corn-to-rats study?

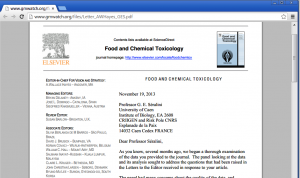

The big news over the weekend was that the journal, Food and Chemical Toxicology, announced that it is retracting the paper it published last year by Séralini et al.

The Séralini paper claimed that feeding genetically modified corn to female rats, with or without added Roundup, caused them to develop more mammary tumors than rats that were not fed GMO corn.

As I discussed in a post at the time, I had my doubts about the scientific quality of the Séralini study. The findings were based on a small number of animals, were not dose-dependent and failed to exclude the possibility that they could have occurred by chance.

In response to readers’ queries about my critique of the science, I added a clarification:

I very much favor research on this difficult question. There are enough questions about this study to suggest the need for repeating it, or something like it, under carefully controlled conditions.

In science, repeating someone else’s study is common practice. Retracting a published paper is not. The editors of Food and Chemical Technology say they are retracting the paper because its findings are inconclusive.

The low number of animals had been identified as a cause for concern during the initial review process, but the peer-review decision ultimately weighed that the work still had merit despite this limitation. A more in-depth look at the raw data revealed that no definitive conclusions can be reached with this small sample size regarding the role of either NK603 or glyphosate in regards to overall mortality or tumor incidence. Given the known high incidence of tumors in the Sprague-Dawley rat, normal variability cannot be excluded as the cause of the higher mortality and incidence observed in the treated groups.

Hello. Where were they during the peer review process? Editors decide whether papers get published. The editors chose to publish the study, even though they had just published a meta-analysis coming to the opposite conclusion: “GM plants are nutritionally equivalent to their non-GM counterparts and can be safely used in food and feed.”

Now, in response to a barrage of criticism (see letters accompanying the online version of the Séralini study), the editors have given its authors an ultimatum: withdraw the paper (which Séralini says he will not do), or they will retract it.

But the editor wrote Séralini:

Unequivocally, the Editor-in-Chief found no evidence of fraud or intentional misrepresentation of the data.

Then how come the retraction? Guidelines for retracting journal articles published by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) say:

Journal editors should consider retracting a publication if:

- They have clear evidence that the findings are unreliable, either as a result of misconduct (e.g. data fabrication) or honest error (e.g. miscalculation or experimental error)

- The findings have previously been published elsewhere without proper crossreferencing, permission or justification (i.e. cases of redundant publication)

- It constitutes plagiarism

- It reports unethical research

The Séralini paper may be unreliable, but that should have been obvious to the peer reviewers and the journal’s editors. Otherwise, the paper does not fit any of the established criteria for retraction.

The anti-GMO group, GM Watch, points out that Food and Chemical Technology is a member of COPE. On this basis, it says the journal’s retraction of the study is ”illicit, unscientific, and unethical.” It has a point.

This is a mess, with the journal’s editors clearly at fault. At this point, they should:

- Admit that the journal’s peer review—and editorial—processes are deeply flawed.

- State that the journal never should have accepted the paper in the first place.

- Announce immediate steps to correct the flawed review processes.

- Apologize to Séralini et al. for having caved in to pressure and blaming him, rather than themselves, for the mess.

- Publish all documentation about the paper on the journal’s website.

- Call on the scientific community to repeat the Séralini study with populations of rats large enough to permit statistical analyses of the results.

About the documentation:

- Séralini, according to a scathing account of this affair in Forbes, plans to sue Food and Chemical Technology for breach of protocol. The Forbes piece finds ”

The entire episode, including the oddly worded retraction statement…a black eye for the beleaguered journal and Elsevier [the publisher].”

- GM Watch posted the “oddly-worded-retraction” letter (from the editor to Séralini) but then took it down. While the link was still active, I took a screenshot. I wish I’d copied the whole thing. If anyone knows where to it, please send the link.

Additions

- Thanks to a reader for sending the entire letter from editor Hayes to Séralini.

- Another reader sent this article suggesting that appointment of a Monsanto-connected editor to the journal may have led to the retraction.