Sometimes I have some sympathy for the makers of High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS). They get such bad publicity.

The most recent example occurred at the White House during the annual Easter Egg Roll, and involved the First Lady of the United States (FLOTUS), Michelle Obama.

Meet Marc Murphy, a chef, drizzling honey over a fruit salad:

MURPHY: “Honey is a great way to sweeten things, it is sort of a natural sweetener.”

FLOTUS: “Why is honey better than sugar?”

MURPHY: “Our bodies can deal with honey…The high-fructose corn syrup is a little harder to … I don’t think our bodies know what do with that yet.”

FLOTUS: “Did you hear that? Our bodies don’t know what to do with high-fructose corn syrup. So we don’t need it.”

OK class. It’s time for a lesson in basic carbohydrate biochemistry.

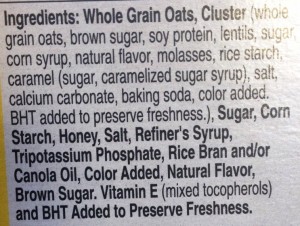

- The sugars in honey are glucose and fructose.

- The sugars in HFCS are glucose and fructose.

- Table sugar is glucose and fructose stuck together, but quickly unstuck by enzymes.

The body knows perfectly well what to do with glucose and fructose, no matter where it comes from.

Now meet John Bode, the new president of The Corn Refiners Association:

We applaud First Lady Michelle Obama’s commendable work to educate the public about nutrition and healthy diets… It is most unfortunate that she was misinformed about how the body processes caloric sweeteners, including high fructose corn syrup…Years of scientific research have shown that the body metabolizes high fructose corn syrup similar to table sugar and honey.

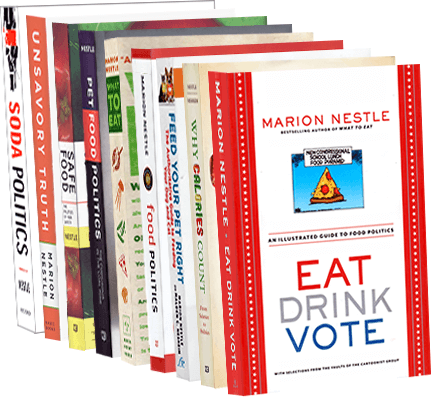

If you’ve been following this blog for a long time, you may recall that I have a little history with the Corn Refiners.

Bizarrely, I was caught up in their lawsuit with the Sugar Association.

And I was not particularly pleased to find several of my public comments about carbohydrate biochemistry displayed on the Corn Refiners website. I did not want them used in support of the group’s ultimately unsuccessful proposal to change the name of HFCS to corn sugar.

I asked to have the quotes removed. The response: “Your quotes are published and in the public domain. If you don’t want us to use them, take us to court.”

I let that one go.

Enter John Bode, the Corn Refiners’ new president and CEO. As it happens, I became acquainted with Mr. Bode in the late 1980s when he was Assistant Secretary of Agriculture and I was working in the Department of Health and Human Services (yes, the Reagan administration).

To my pleasant surprise, he recently wrote me “warm greetings, after many years.” His note assured me that my request to have the quotes removed would be respected and that they would soon disappear. And so they have, except for a couple in some archived press releases.

Score one for John Bode.

Mr. Bode has his work cut out for him. He has to teach the world carbohydrate biochemistry, restore public acceptance of HFCS, defend against Sugar Association lawsuits, stop the Corn Refiners from being so litigious, and do some fence-mending, all at the same time.

And he must do all this in an era when everyone would be better off eating a lot less sugar of any kind, HFCS included.